Sometimes You Just Can't Go Back...So Much for the NASB

And such is life.

Kathy sat me down on the couch this morning, and in no uncertain terms told me, “You can’t teach with whatever translation you’ve used the last two Sundays anymore!”

“Why not?” I sheepishly asked. Although I knew better. I had read the word “booty” from that Bible in front of forty people in our Bible study to the snicker of some and to the red face of my wife. Who uses that word anyway--pirates?

She went on to tell me that every time I read anything from my Bible, it was hard to understand and too different from anything anyone else was reading from. She said, “No one could even follow you!”

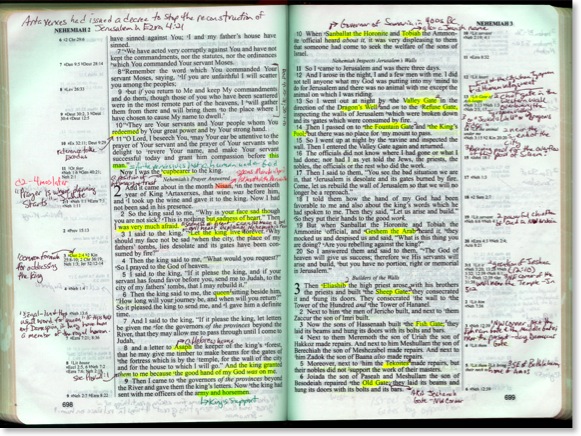

I reached for the Bible to which she was referring. I opened it up and showed it to her. “But I like this Bible. It has wide margins. I teach better when I use it.”

“Better for you, maybe, but not for anyone else. So you have to decide--are you going to teach in a way that’s easier for you or easier for those listening to you?”

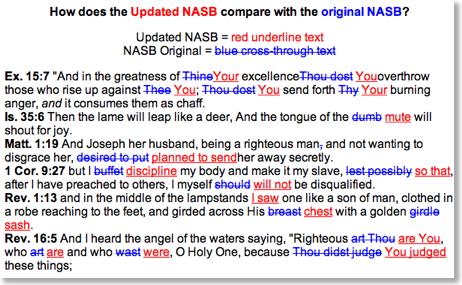

Here’s what happened: two weeks ago, I did the unthinkable--I went back to my NASB for teaching our Sunday morning Bible study. I taught from the NASB for almost two decades, and then in 2005, while teaching a half year study on Romans, I realized I was spending more time explaining the English of the NASB than explaining what Paul actually said in Romans. I have always been an advocate of modern language translation, but I always felt that in a teaching setting, I would be able to use something a bit more formal. I quit doing that in 2005.

Since then I’ve used a variety of translations--going first to the HCSB and then the TNIV as my primary teaching Bible, but also using the NLT quite a bit and even the NET Bible.

...But I was frustrated. Part of my method all those years involved taking notes in a wide margin edition, and then using that edition when I’m teaching. I carried notes on paper, too, but the subset in my margins were little reminders of the most important information to get across.

Two decades ago, my goal had been to study biblical languages to the point that I no longer needed translations at all. I always carry at least my Greek New Testament with me, but I have two problems with totally abandoning English translations: (1) I simply don’t have every word in the NT in my working vocabulary. Yes, I can prepare a passage beforehand to teach from. But the first time I think of another passage to look at, or the first time someone says, “What about this verse?” I look at that and can translate everything except those two words. So it’s never been practical on the fly to try do that exclusively--at least not yet. And (2), I’m hopefully a bit humbler now, but I recognize that my “on the fly” translation, even if I know every word, is not necessarily better than a standard translation produced by a committee made up of people who are surely smarter than me.

So I continue to use both, using a translation as a primary text when I’m in front of others.

After abandoning the NASB, the translation I’d used since I was thirteen-years-old, I assumed I’d be able to get one of these more modern translations in a wide-margin edition. No such luck. So I thought I’d be patient and wait, but now after three and a half years, still no luck.

Sunday before last, I did what I had been tempted to do many times before, I taught from my trusty old Foundation Press wide-margin NASB. It felt good. I felt like I was spending time with an old friend. And even teaching from Isaiah 38-39, I managed to get away with it, partly by letting people in my class read sections that were...what can I say...a bit awkward sounding. But I made it, I felt like I was a better teacher, and I planned to go on and use my trusty NASB for a second week.

Then this past Sunday, we were running short of time as is often the case. With only a couple of minutes to go, I offered to read vv. 11-12 of Isaiah 53. As I begin to read...As a result of the anguish of His soul...I can already see it upcoming in v. 12 in my peripheral vision. My Servant, will justify the many, As He will bear their iniquities... This is what I noted in my preparation that I absolutely must not read publicly...Therefore, I will allot Him a a\portion with the great... I tried to think of all the other translations that I looked at ahead of time. What word did they use for שָׁלָל? Spoil (HCSB, ESV, JPS, NKJV, NRSV, REB), spoils (TNIV, NET)...it was right there swimming about my brain, but I couldn’t remember. And then I read it... aloud:

And He will divide the booty with the strong

I heard chuckles. I could see heads lifting up, including my wife’s. I knew what they were thinking. Did he just say... ? Surely not. No one except for teenagers and pirates say that.

So, the heart-to-heart talk this morning came as no surprise. She had all the conviction of Sarah telling Abraham that Hagar had to go, so who was I to argue with her?

So, I’ll go back to my non-wide-margin Bibles, and wait hopefully that one day, I’ll get a wide margin Bible in a modern translation. But what do I use this Sunday? For the last couple of years, I’ve used TNIV on Sundays mostly, and the NLT during the week. But sadly, I have doubts about the staying power of the TNIV. So maybe this is simply the time to switch.

I use the NLT with my college students midweek because not all of them are believers, and the NLT has the most natural conversational English of any major translation. As I used it tonight with a class, I had to ask myself why I couldn’t use it on Sunday mornings, too? And I don’t have a good answer for that. So maybe this is the crossroads in which I simply need to make the NLT my primary public use Bible. I may have been held back by nothing more than my own traditionalism, but after listening this past week to Eugene Peterson’s Eat This Book, I’m more convicted than ever to present the Scriptures in common, ordinary language, and not the language of heavenly-portals-loud-with-hosannas-ring.

But what do I use? There’s still no wide-margin NLT. I’d certainly want the 2007 edition. So what are my options?

The NASB & the Rejection of Markan Priority

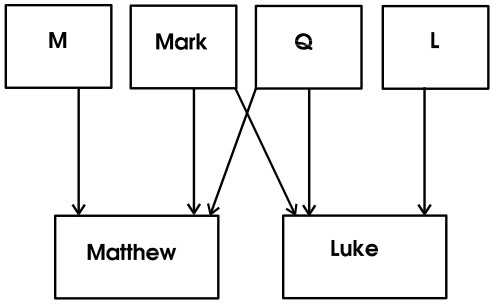

Markan priority--the idea Matthew and Luke independently used Mark's gospel as a starting point, along with the so-called Q source and their own independent traditions--is almost universally accepted in biblical scholarship across almost all theological persuasions.

Consider the late F. F. Bruce on the subject in his article on the Gospels in The New Bible Dictionary:

This finding [the idea of Markan priority], which is commonly said to have been placed on a stable basis by C. Lachmann in 1835, depends not merely on the formal evidence that Matthew and Mark sometimes agree in order against Luke; Mark and Luke more frequently against Matthew; but Matthew and Luke never against Mark (which could be explained otherwise), but rather on the detailed comparative examination of the way in which common material is reproduced in the three Gospels, section by section. In the overwhelming majority of sections the situation can best be understood if Mark’s account was used as a source by one or both of the others. Few have ever considered Luke as a possible source of the other two, but the view that Mark is an abridgment of Matthew was held for a long time, largely through the influence of Augustine. But where Matthew and Mark have material in common Mark is fuller than Matthew, and by no means an abridgment; and time after time the two parallel accounts can be much better explained by supposing that Matthew condenses Mark than by supposing that Mark amplifies Matthew. While Matthew and Luke never agree in order against Mark, they do occasionally exhibit verbal agreement against him, but such instances mainly represent grammatical or stylistic improvements of Mark, and are neither numerous nor significant enough to be offset against the general weight of the evidence for Mark’s priority.

In seeking to confirm Wilkin's statements from 1995, I have been in correspondence with a person at the Lockman Foundation over the past couple of weeks in regard to this subject. Although I was not given permission to quote any of the statements from the representative of the Foundation as they consider them private correspondence only to me, I am allowed to confirm that the rejection of Markan priority is indeed a conviction on the part of the NASB translators.

What difference would it make whether a translator holds to Markan priority or not? Well, I have to walk a bit of a discretionary tightrope here regarding the exact nature of the explanation given to me by the representative of the Lockman Foundation. Suffice it to say, at the very least, it involves (according to them) how a translator might view parallel accounts between the synoptics that contain conflicting information. Are they the same event with actual conflicting details or are they two separate, but similar events? This, evidently, is the issue to the translators. Also, there is concern on the translators part that adherence to Markan priority may affect one's view of inspiration. I can't say much more than that as I may have already relayed more than what is appropriate in the request given to me for confidentiality, although I have attempted to be vague in the statements immediately above. I wish I could be more specific regarding the explanation given to me by the Lockman Foundation.

But I have a few questions for the readers of This Lamp. (1) Am I late to this information, or has anyone else ever heard of the rejection of Markan Priority by the NASB translators? (2) Granted the early church held to a position of Matthean priority, but as far as I know, most biblical scholarship--including Evangelical scholarship--rejects the traditional position in favor of Markan priority. Therefore, how widespread is a rejection of of Markan priority among respected scholarship? (3) As I look at the list of other translators for versions such as the ESV, NLT, TNIV, NET, HCSB, etc., I cannot imagine a unanimous rejection of Markan priority on any of these other committees. Am I simply mistaken? And finally and most importantly, (4) would acceptance or rejection of something like Markan priority truly make a difference in the accurate translation of the Synoptic gospels? Would not an honest translator simply render the text as it is?

For the record, I believe Markan priority is the best offered explanation of the so-called synoptic problem. Frankly, I'm surprised that the entire committee of a modern translation would have unanimous and wholesale rejection of it. Your thoughts are welcome and encouraged in the comments.

Missing My Wide Margin NASB

Frequent readers of This Lamp will remember that although I've always been an aficionado of Bible translations, I used the NASB for almost two decades in teaching and preaching settings until I became convicted a couple of years ago that the formality and literalness of the translation itself was getting in the way of what I was trying to teach. Since then, I have primarily used the TNIV in public, but I've also used the HCSB and NLT to a certain extent as well. And often even when needing to carry a translation to a setting where I wasn't presenting, I tended to pick up my TNIV.

But yesterday is a good example of this "change" in my habits. I've been meeting a friend of mine for breakfast for a couple of years now, and we usually read a book together and discuss it over bagels. Over the last few weeks we've been reading Bonhoeffer's Cost of Discipleship. Yesterday as I was heading out the door to meet for breakfast, I grabbed a Bible as I always do. But instead of grabbing the TNIV Study Bible which has been my practice for a few months, I picked up my wide margin NASB.

Doesn't the TNIV Study Bible have notes? Sure it does. But the notes in my NASB are my notes. These notes are the facts and insights that stuck out to me. These notes are the triggers I used to discuss the text when I was teaching it last. The TNIV Study Bible is the first study Bible that I have ever consistently carried with me. It's notes are helpful, but I find that I don't automatically turn to them. I look at them if I need to look something up and hope that the information I need is there.

After using other Bibles for over a year and a half now, I have to admit that i really miss my wide margin NASB. And I don't think it's the NASB that I miss so much, although I will always have a great familiarity with it. What I miss is the ability to refer to my notes, to refer to a tangible experience of having spent time--studied and wrestled--with a particular passage before. I don't have notes on every page of my Bible. But the notes that I do have are footprints that I was there, evidence that I stopped and camped out a while, as opposed to merely passing by.

I stay in a continuing conundrum. I really do feel committed to public use of a contemporary translation. And I would prefer a gender-accurate, non-Tyndale translation when presenting in front of mixed audiences. But no usable wide margin edition of a contemporary translation exists that meets these factors. There is no wide margin NLT and the only wide margin TNIV offering limits writing space to one column on a two column page and has paper too thin for extensive use. I might be willing to settle for the HCSB even though it is not gender accurate, but the pages in its only wide margin offering are so thin that they curl when writing on them.

At this point, I would like a new wide margin Bible (leather, of course) in a contemporary translation--any translation. I'm willing to transcribe my notes even a third time. TNIV? NLT? NET? HCSB? Something else? At this point, I'm not even overly concerned with the exact translation, in spite of the fact that I have my personal favorites and feel some are better suited for teaching than others. Whichever publisher first delivers a wide margin edition in one of these translation wins--at least with me.

Every Sunday morning when I leave for church, I push aside my wide margin NASB in favor of the TNIV Study Bible. Despite the fact that as I've studied a passage that I will be teaching I've taken diligent notes in the margins of my NASB, I've been forced to create a subset of these notes in the anemic margins of the TNIV Study Bible or in whatever white space I can manage. But the temptation to grab my trusty NASB and run remains. And I wonder if this temptation is growing stronger?

NASB vs. NRSV Round 5: Epistles & Revelation

This is the final round of comparisons between the NASB and the NRSV. The fourth round was posted over a month ago, and the info below has been sitting around in the comments of a much earlier post for a while now. You'll remember that this started after I made comments about the literalness of the NASB. This Lamp reader, Larry, challenged that assertion in favor of the NRSV, one of the translations he favors. This extended series of comparisons examined 50 verses from throughout the Bible, randomly selected. Although the NASB took an early lead (as I predicted), I should remind readers that literalness does not equal accuracy. Every verse/chapter/pericope must be evaluated separately. Regardless, here is the fifth round and final results of this series.

| Reference | Rick's Evaluation | Larry's Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

Rom 10:21 |

The versions are very similar and functionally the same in these verses. I give the NASB a slight edge because ten is translated in the NASB in the phrase “all the day long” as opposed to the NRSV’s “all day long.” Also I believe “stretched out” is a better rendering of exepetasa than “held out.” | This is a fascinating verse to consider, because it is one of many verses that quote the Septuagint. To the credit of both the NASB95 and NRSV, they have translated the Hebrew independently of the Greek (although the NRSV is the superior translation of Is 65:2).

Now this passage presents a particular problem because it does not even correctly quote the Septuagint we now have. Thus, the footnote in the NASB95 is rather misleading, and because of this reason, I call this for the NRSV. |

1 Cor 3:10 |

At first I was surprised that the NRSV would use “skillful” over the NASB’s “wise” for sophos. But in looking at the BDAG, the first definition for the word is “pert. to knowing how to do someth. in a skillful manner, clever, skillful, experienced.” The second meaning is “pert. to understanding that results in wise attitudes and conduct, wise.” Thus either rendering is correct based on how the translators determined context. At this writing, I’m not sure which rendering I favor. “Wise” is certainly more traditional and also found in the KJV, but that doesn’t mean it’s more correct than “skillful.” The last sentence in this verse is interesting because at first glance, one might suppose that the NRSV’s each builder is an attempt to use inclusive language over the NASB’s each man. But that is not the case. The actual word in the Greek is hekastos which is more correctly translated “each person.” Knowing that the 1995 update of the NASB cleaned up some of the masculine oriented language in these types of verses, I’m surprised to see the NASB’s rendering. There is not a separate word for “man” in this verse, just as there is no separate word for the NRSV’s “builder.” Yet the NASB introduces masculine specificity where it is not represented in the text. The KJV uses “another” and even the ESV renders the word “someone else” (as does the NIV). Based on this, I’m giving the verse to the NRSV. | I agree with Rick. NRSV. |

2 Cor 3:4 |

Neither verse translate de. I don’t really fault the NRSV for inserting “is” although the lack of it in the NASB brings that version closer to word for word literalness. The use of “that” by the NRSV is totally unnecessary. When I teach writing classes, I tell my students that if they can eliminate the word “that” in a sentence and it still makes sense to do so. This verse goes to the NASB. | I don't understand Rick's analysis here. The NASB95 is ambiguous in English (it could be interpreted as "confidence such as this have we ..." or "[wow], such confidence!" ) while the NRSV refers clearly to the pepoithesin just expressed, namely: Paul doesn't need (no stinkin' badges) any credentials other than testimony expressed by the existence of the Corinthian church. Certainly, a translation cannot be regarded as literal if it has a meaning different than the original or unnecessarily introduces an ambiguity. I call this for the NRSV. |

Col 2:13 |

The NRSV includes the kai which the NASB removes for readability purposes. But the NRSV inserts “God” where it does not actually appear in the text. This is offset by the translational note, however. Although this is contextually correct, it does not accurately reflect the text. I don’t personally have a preference for “transgressions” vs. “trespasses” for paraptoma. I’m calling this one a tie. | Since our ground rules were to count textual notes in our analysis, I can't count the extra "God" against the NRSV. For the reasons observed by Rick, I thus weigh the factors towards the NRSV. |

Col 3:13 |

The NASB does a better job of keeping the particples in place, which the NRSV has altered to become simple imperatives. "bearing" in the NASB captures the participle anechomenoi much better than "Bear" in the NRSV just the same as "forgiving" is a closer equivalent to charizomenoi than "forgive."

The NASB fails to capture the conditional ean which the NRSV does represent with "if." However, the last phrase in the original, houtos kai humeis is literally represented in the NASB's "so also should you" as opposed to the NRSV's "so you also must forgive." Thus, overwhelmingly, this verse goes to the NASB. |

I agree, the NASB95 is more literal here. |

1 Tim 6:6 |

This verse is part of the same sentence as the previous verse (following NA27). The NRSV translators chose to create a break and make a new sentence as opposed to the NASB which follows the structure set in the NA27.

Should I even point out that the NRSV begins the verse using a pronoun that lacks an antecedent? The phrase oudeis anthropon would literally be "no one of humans." Neither version chooses to translate this phrase literally. The NASB chooses "no man" while the NRSV chooses "no one," each opting to ignore half the phrase. Of course, neither translation can be faulted as an actual literal translation would prove awkward in English. All that to say, I'm calling this verse a tie (in spite of the NRSV's questionable grammar). The NASB follows the sentence structure better, but the NRSV includes the conditional. |

I'm not sure I understand your point about the NRSV's "he" lacking an antecedent -- certainly it is present in the preceding verses. However, I'll go along with your calling it a tie. |

Clarification: |

I was referring to the NRSV's starting the sentence with it, a pronoun, actually referring to the he that comes after it--which by defintion can hardly be an antecedent to the pronoun. This is hardly good prose, but it didn't affect my scoring for that verse. | That's not ungrammatical, just awkward -- the "it" matches with the "who" clause. The NASB95 uses this sentence structure in its translation of Daniel 2:21, for example.

However, the NRSV is not very faithful here to the Greek. |

Heb 10:9 |

There's not much to functionally distinguish between the versions in this verse. However, based on the theological context of the larger passage, I like the NRSV's use of "abolishes" for anairei than the NASB's "takes away."

So, I give this verse to the NRSV. |

I disagree, and call this for the NASB95 -- largely because of the footnote which more accurately reflects the tense. |

Heb 10:19 |

I have never liked the NRSV's use of "friends" for adelphoi. In my opinion "friends" loses the familial aspect of the word in Greek. I don't know why the translators did this sometimes because in other places such as Rom 1:13, "brothers and sisters" is used which is a perfectly valid translation.

I don't think "holy place" vs. "sanctuary" is an issue for hagion since both mean the same thing. Literally the verse reads "the entrance into the holies," but neither version translates it this way. Tie. |

I also count this as a tie -- "sanctuary" is closer to the Greek, but so is brethren. |

James 2:8 |

I'm giving this to the NASB for the following reasons: (1) the NASB follows the word order more closely than the NRSV, (2) the NASB translates Ei mentoi whereas the NRSV does not, and (3) the NASB provides an alternate translation and the NRSV does not. | I agree, this goes to the NASB95. |

James 2:9 |

Umm... tie. | This is very close -- the difference is between "commit" and "are committing". Normally, I would say that "are committing" is closer, but the later translation of "are convicted" rather than "are in the state of conviction" (which doesn't sound very good in English) presents a problem. Both egarzesthe and elenchomenoi are present tense in the Greek, but I am not sure how to translate this into English using only present tense verbs. The Vulgate captures this with si autem personas accipitis, peccatum operamini, redarguti a lege quasi transgressores but in English something has to give. Given that, I think the NASB95 and NRSV are both approximately close, so I agree this is a tie. |

Final Comments: |

Too bad we didn't have any verses from Revelation. My comments will be very brief. The fact that the NASB is more literal than the NRSV is certainly no surprise to me. I like the literalness of the NASB for personal study, but it is no longer a translation I would use for public reading. This is not so of the NRSV, which in my opinion is the most readable of all Tyndale tradition translations. Claims are made that the ESV is more readable than the NASB, but I don't buy it, simply because the ESV is not a consistent translation regarding issues like readability. I will say this, however: our little exercise here has renewed my appreciation for the NRSV. I have not used it much in the last few years, but it is not deserving of the neglect I've given it. Although I prefer the NASB for a literal Tyndale translation, and a version like the TNIV or even NLT for public reading, the NRSV has its place somewhere in between. Thank you, Larry, for suggesting this comparison. I would be interested in comparing some other translations. Next on my plate is the NLT vs. CEV comparison with Lingamish, but after that perhaps we could do an NRSV vs. ESV comparison. Now that would be interesting. |

(a) It was interesting to me that when we chose verses at random, small textual issues dominated those that gain the most headlines: gender, "Christianized" readings of the Hebrew, etc.

(b) I was disappointed with the great differences in the philosophy of how the Hebrew and Greek were translated. In general, the Hebrew received less attention. Roughly speaking, the Hebrew Scriptures are about three times the length of the Greek (ignoring the Deuterocanonicals for a moment), and it appears to me that translation teams do not proportionally divide their efforts. (c) The difference in literalness between the two translations is not that great. By Rick's count, the NASB95 was more literal only half of the time, while the NRSV tied or was more literal the other half of the time. My count was similar -- with the NASB95 being more literal 42% of the time, with the remainder having a tie or the NRSV being more literal. (d) While this exercise increased my respect for the NASB95, I still think the results are close enough for other factors to be considered in choosing a literal translation: availability of desired editions (e.g., wide margin editions [where the NASB95 has the advantage], academic study editions [where the NRSV has the advantage]), ecumenical focus [NRSV], conservative interpretation [NASB95], availability of deuterocanonicals [NRSV]. (e) Given that the NASB95 and NRSV are relatively literal translations, it is a pity that there aren't more diglots or other original language resources available. To the best of my knowledge, there is no joint edition with the Hebrew. The Deuterocanon has the Parallel Apocryhpa (with the Greek and NRSV), and there are some interlinear editions of the New Testament with the NASB or NRSV as well the convenient, but out of print, Precise Parallel New Testament with the NASB, NRSV, Greek, and five other English translations. (f) I think our method for evaluation was far better than the typical bible comparisons found on the web where only certain "hot button" verses are compared. While the latter allow charges of heresy and bias to be thrown around, I think the method we used gives a better picture overall. I understand that Rick and David Ker will begin a comparison of the CEV and NLT. I don't spend a lot of time with these versions, so I'm looking forward to seeing their insights. |

Cumulative Scores: |

Torah: 1 (NRSV) - 6 (NASB95) - 3 (tie) |

Torah: 2 (NRSV) - 4 (NASB95) - 4 (tie) |

Completing the Boxed Set:

NASB vs. NRSV

NASB vs. NRSV Round 1: Torah

NASB vs. NRSV Round 2: Nevi'im

NASB vs. NRSV Round 3: Kethuvim

NASB vs. NRSV Round 4: Gospels & Acts

Comments where these discussions were taking place

NASB vs. NRSV Round 4: Gospels and Acts

| Reference | Larry's Evaluation | Rick's Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

Matt 13:37 |

The NASB95 alone translated "de." (Isn't it inconsistent for it to translate "de" but not translate initial vav's in the Hebrew?). Neither version full translates apokritheis eipen. The translation of the KJV is more literal here "He answered and said ...." although it immediately deviates after then because of its use of the TR. Nonetheless, I regard apokritheis as the more important term here, especially as it connects the explanation of the parable to the question of the disciples in the previous verse. So the NASB95 gets the nod for translating "de" but the NRSV has a better translation of "apokritheis eipen" -- tie. |

This is a close call. You're right about the deficiencies of both in regard to apokritheis eipen, but both translations made a good call by stripping down what amounts to a redundancy in English. I want to call it a tie as well, but in my opinion, the NASB's translation of de makes it (ever so) slightly more literal than the NRSV. So I'm giving it to the NASB, but BARELY. |

Matt 21:27 |

Well, here the NASB95 translates both words apokrithentes and eipan, so it is more literal, and translates kai consistently in the verse. | Agreed: NASB. |

Matt 23:33 |

The NASB95 (in a footnote) captures the subjunctive in phygete and also finds two one word translations of kriseos. It is more literal. | I agree with your analysis and would add that "sentence of hell" better captures the genitive construction of kriseos tes geennes. NASB wins here. |

Mark 8:16 |

Translating deilogizonto as "said" does not do it justice. On the other hand, why does the NASB95 add the completely unhelpful "began". The NRSV makes this a direct quote, although tries to make up for its previous mistranslation of deilogizonto by inserting, out of thin air, "It is because" and changes echousin to first person plural. There is no contest here. The NASB95 is far more literal. | I agree with the unnecessary additions of the NASB. But like you, overall, I see the NASB as more literal here. |

Luke 8:32 |

Both versions are commendably literal in translating this verse. The NRSV moves up hillside here, but the change is minor. The NASB95 translates "there" twice here, one appears to be from "ekei" but I cannot find from whence it obtained the second "there". I'm calling this one for the NRSV. | I believe the second use of "there" in the NASB is the actual translation of ekei. The first is merely part of the translation into good English. However, the NRSV found a way to keep this literal without it, so I, too, give the nod to the NRSV, but it's a very slight nod. |

Luke 18:29 |

Other than capitalization (not an issue in original manuscript Greek) and "say to" versus "tell", these are identical. Tie. |

Agreed. Tie. |

Luke 21:7 |

There is no attempt here to represent the de, but the NASB95 does separately translate the Eperotesan & legontes, pote & oun and more accurately translates the single word (out of context) hotan. On the other hand, it adds an interpolated "things." I give a slight nod to the NASB95. | I agree that the NASB is more literal, but I feel it is a good bit more literal than a simple slight nod. Regardless, NASB gets this verse. |

John 3:28 |

If one includes alternatives, the NRSV and NASB95 are essentially the same here -- it is a tie. I'm not sure why the NRSV and NASB95 put in the footnotes they did given the later use in John 4:25. (Off topic: did other viewers notice how horrible the Aramaic pronunciation was in Gibson's Passion of the Christ? For example, the High Priest pronounces "messiah", repeatedly, in mixed up Hebrew and Aramaic: meshiaha.) | I agree to the tie. I agree that "having gone before" would be a more literal translation than either option in the NASB or NRSV. As to the off-topic question, I didn't notice. However I remember when I saw the movie wondering how mangled the pronunciations were in general with so many non-Aramaic speaking actors. After viewing it at the theater, I've never gone back to watch it on DVD. And I'm not sure I ever will. It's a difficult movie to watch. |

Acts 20:13 |

Here the NASB95 translates the "de", so I don't understand its translation philosophy for Greek -- it appears inconsistent to me. There is a substantial difference in the translation of proelthontes. Since this is an aorist participle, wouldn't the literal translation be "having gone before"? Perhaps the translations intend to capture this by using "ahead", but that seems an inadequate to me. I can't make up my mind which of the verb forms used "going" or "went" is close to "having gone before" -- neither seems particularly accurate to me.

In this case, I'd call it for the NASB95 [purely on the basis of having translated the "de"], but neither is as literal as the KJV. |

Agreed. The NASB is more literal. |

Acts 28:23 |

Taxamenoi is another aorist participle, so I would translate it "Having set in order." The NASB95 translates ekitheto diamartyromenos as "explaining [to them] by solemnly testifying" while the NRSV opts for "explained the matter" Of course the middle voice doesn't exist in English, so an exact translation is impossible; the NASB95 captures the notion of testifying and adds "solemnly" (which does not capture the clear sense of thoroughness that context demands here, but which is literal enough.) So I call this for the NASB95. |

Another agreement for the NASB. |

Additional Comments: |

A blow-out for the NASB95

I'd like to make some additional comments here. The NASB95 has a decidedly different character in translating the Greek Scriptures than the Hebrew Scriptures; it hews much closer to the text and shows greater care in translation. At the same time, it is neither as literal as the KJV was to the Textus Receptus and certainly is not as elegant as the KJV. The NRSV also changed character in the Greek Scriptures -- it almost adopted an "easy reading" character I identify more closely with the NIV. What accounts for this difference? I have some preliminary speculation. For the NRSV, perhaps because the Gospels and Acts is more straightforward than the more alien, ancient, and ambiguous language of the Hebrew Scriptures, the translators felt more comfortable putting the Scriptures in plainer language -- they didn't think they would go astray so easily. For the NASB95, given that the Greek Scriptures are more important to their audience than the Hebrew Scriptures, I simply think they devoted more time to them. I must say that in reading these verses, I am more impressed than ever with the achievement of the KJV (and Tyndale), which manages to present both Hebraized English and relatively literal Greek while maintaining a consistent tone (perhaps too consistent, since the original differs so greatly in tone) and also maintaining elegance and also using (for its period) simplified English. |

Larry, in regard to your final thoughts on this section, I think we are in agreement that both translation committees seemed to have taken more care in their translations of the New Testament. This might explain my earlier comment that analyzing these verses seemed easier than the previous ones in the OT, and I don't think it was simply the fact that my Greek is (much) better than my Hebrew. The difference in character between the testaments in these translations may just be another instance of a long standing tradition of slighting the Old Testament. At some point, it might be interesting to do a similar analysis, although obviously not on literalness, with a translation like the NLT. I know that one of my former OT committee members, Daniel I. Block, was very influential in the translation of the NLT OT, and much of the changes between the NLT1 and NLT2 I woul guess came at his insistence.

Regarding the nature of the NRSV NT that you mentioned, I had always thought of the NRSV as being a bit more in flavor like the NIV, and these verses certainly seem to demonstrate. I can only guess that my experience with the NRSV (primarily in my M.Div years) was rooted more in the NT than the Old (see, there's that bias again). |

Cumulative Scores: |

Torah: 2 (NRSV) - 4 (NASB95) - 4 (tie) |

Torah: 1 (NRSV) - 6 (NASB95) - 3 (tie) |

To read more click the following links:

NASB vs. NRSV

NASB vs. NRSV Round 1: Torah

NASB vs. NRSV Round 2: Nevi'im

NASB vs. NRSV Round 3: Kethuvim

Comments where these discussions are taking place

NASB vs. NRSV Round 3: Kethuvim

One note of difference from previous posts, though. I have switched myself to the left column and Larry to the right column for this post since I was able to write my analysis first this time.

| Reference | Rick's Evaluation | Larry's Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

Psalm 22:26 |

It's interesting that the NASB renders ‘anaw "afflicted" and the NRSV, "poor" and both offer the other's rendering as an alternate translation. Either word is suitable and part of the glosses included in most Hebrew lexicons.

I also found it interesting that the NRSV retains the use of "shall" while the NASB changed its wording to "will" in the 1995 update. These words are used interchangeably in today's vocabulary and any traditional distinction is ignored. Finally, I was about to call this one a tie, when I noticed that the 2nd person plural suffix added to levav is better reflected in the NRSV's "your hearts" than in the NASB's "your heart." So, in light of that, I'll give the nod to the NRSV as being more literal. |

I can't agree with you here on the disappearance of the shall/will distinction -- it is still in the (grammar) books, after all. However, more on topic: I also don't completely agree with you on "your hearts". This is one of those phrases that is easily translated into English -- chem is indicating that your is masculine plural but the root levav is actually singular. Thus the BDB translates it as "you yourselves." There is a deeper problem here. There is an ambiguity in the Hebrew text. Who is the subject of your this line? One possibility is that it is the Deity, and "chem" is being used as a royal identifier (or, a Messianic Christian interpretation that views this another triune reference.) The NASB95 translation allows this ambiguity while the NRSV seems to preclude it. For this reason, I would disagree with you and say the NASB95 is more literal here, since it preserves the ambiguity. |

Psalm 37:6 |

I don't feel much detail is needed here, but Larry can challenge me on this if he wants to. Although I would feel that the NRSV brings out the meaning of the verse more clearly, the NASB gives a much more literal, word-for-word translation. And since that is what we are judging on, I claim the NASB to be more literal. | I don't understand why both the NRSV and NASB95 change the word order between k'or and tzidkecha. Nonetheless, I agree that the wording of the NASB95 is more literal here. |

Psalm 104:34 |

Neither one of these verses translate ‘arav literally as "sweet," although "pleasing" captures the meaning of the idiom for English speaking audiences. The NASB attempts to reflect the extra pronoun ’anokhi [literally, "I"] in the phrase "as for me." There's no easy way to do this because samach (I [will] rejoice) is also first person singular and can create an unnecessary redundancy in English. However, it is in the Hebrew for added emphasis and since the NASB attempts to refelct this (albeit awkwardly) and the NRSV does not, I have to claim that the NASB is more literal. Larry may decide to challenge this. |

Anokhi is an interesting word, in that it carries special emphasis; famously at the start of the Ten Commandments. Nonetheless, I don't think that the NASB95, although it tries to reflect this emphasis, is a more literal translation -- in fact, it is just odd to me: "as for me" suggests a comparison -- suggesting the NASB95 is translating Anokhi in opposition to the Lord. But this is Hebrew poetry and the parallel structure is not in opposition but in sympathy. Thus, the reading of the NASB95 is opposite to what the psalmist is saying here. I'm not so sure that this is a case of the NASB95 not being literal as it is of the NASB95 simply being wrong. Even worse, the introduction of the extra phrase "as for me", even if it is not interpreted as being in opposition, breaks the symmetry of the poem. For this reason, I regard the NRSV as more literal. |

Psalm 118:8 |

This may be the first verse in which we've truly had to wrestle with the NRSV's inclusive language [i.e. "mortals" as opposed to "man"]. Any regular reader of this blog knows that I am not opposed to inclusive language as it often better communicates the meaning of the original message. This is case in point where I have offered anecdotal evidence in the past that masculine universals do not always communicate well in today's culture.

So, on one hand, I have no problem with the NRSV's use of "in mortals" for ba’adam as opposed to the NASB's "in man." However, in terms of literalness, the word "man" is singular (even if representing the plural) like the Hebrew singular absolute, while mortals is plural. Maybe this is splitting hairs, though. In which case, I'll give the nod to the NASB based on the fact that "trust" is word-for-word more literal for batach than the NRSV's "put confidence." So I say the NASB is more literal, but if it's any consolation, I like the NRSV's wording here better. |

Had the NRSV included a footnote here, I would have excused the introduction of the plural mortals. (By the way, this is not the first time we've dealt with this -- there is a fathers/ancestors dichotomy in both Deut 13:6 and Isa 64:11 but here it is more intrusive, because of the switch to a plural.) I give the nod to the NASB95. |

Prov 6:33 |

The NASB reflects the word order of the Hebrew in the opening line more closely. However, I've already stated in this series analysis that I don't find fault in translators shifting the verb for better English translation. Therefore, I call this verse a tie. |

It is true that the NASB95 better reflects word order here, but I do not understand how the NASB95 derived "not be blotted out" from "lo timacheh". The root M-CH-H is normally translated as wipe (this is particular clear in 2 Kings 21:13) -- and this particular clear in cases of writing (e.g. Moses name in Exodus 32:32-33). The "blot out" sense listed in BDB, for example, is not found in HALOT -- it means in the instances used as "annihilate." I this this is a case where the Evangelical leanings of the NASB95 translators show all too clearly; the translators are perhaps trying to steer the reader away from the metaphor of "washing" sin away. I could call this a draw (word order versus word choice), but I think the word choice here is so misleading that I will call this one for the NRSV. |

Job 36:5 |

These translations are identical except for the way each translates the first Hebrew word, hen. Generally, this is translated "behold" as in the NASB, but according to the BDB, it can be seen as a hypothetical participle propounding a possibility. I'm under the assumption that this is what the NRSV translators had in mind when they rendered hen as "Surely." Therefore, I call this verse a tie. |

If I were going to make the rules all over again, I would exclude verses from Job on the basis that the meaning of the text is so unclear in so many places. This verse is a perfect example -- while the words in this verse are clear enough, it has an ambiguous reading:

Behold God is mighty and rejecteth not; He is mighty in strength of understanding. Or as the New American Bible translates it: Behold, God rejects the obstinate in heart; he preserves not the life of the wicked. Or as the New Jerusalem Bible translates: God does not reject anyone whose heart is pure. [This appears to be following the Septuagint, but can be read into the Hebrew, i.e., Behold God is mighty but does not despise those with mighty, strong, understanding.] Or as the New English Bible translates: God, I say, repudiates the high and mighty. I must say that I am considerably annoyed at the way that both the NRSV and NASB95 confidently translate the text throughout the book. For lacking what I consider absolutely necessary footnotes here, I am calling this a tie. |

Lam 3:59 |

Let me give my own literal reading for this verse: "You have seen, YHWH, my oppression / judge my judgment [shafeta mishpati]."

This is very close, but despite word order on the part of either translation, the NASB is more literal in its use of fewer words in the first line. "Case" may also be more literal than "cause" for mishpat. Therefore, I consider the NASB slightly more literal. |

I see your point here, but I was a little surprised you accept an archaic reading of obscure. Of course, I am compelled to accept it, so I agree that the NASB95 is superior here. |

Dan 11:23 |

To me this is a difficult verse to put into English. Regardless, I am going to go for a tie because of the deficiencies of both translations. The NRSV completely leaves out any translation of we‘ala [reflected in the NASB's "and he will go up"], but I don't think the NASB's insertion of the italicised (i.e. added) "force of" is all that helpful or accurate. |

I agree with your analysis, but weigh the factors differently, so I'm calling this for the NASB95. |

Neh 8:14 |

The NRSV translates the initial vav that the NASB removed in the 1995 update for readability. And although it's another inclusive issue, I feel that "sons" in the NASB is more literal than "people" in the NRSV for bene.

One vs. one creates another tie. |

I'd like to point out the KJV uses "children of Israel" here. Gee, even the ESV uses "people of Israel" here. The problem is that bnei-yisrael is a single semantic unit and it everywhere means Israelites. (Semantic units are mistranslated if broken up -- one does not gain insight into "left bank" by translating "left" and "bank".) Indeed, the Rabbinic writings interpreted the commandment to live in a sukah) as binding on women. Now, one of the most silly aspects of the NASB95 is how it translates everywhere in Exodus 1, for example, bnei-yisrael as "sons of Israel" rather than Israelites. Strangely, though, the NASB95 translates yeled as "child" (twice) and in this case, yeled definitely meant a male, since it was Moses. [Perhaps this is an Evangelical choice, to echo a more famous phrase beginning "son of."]

Other differences: The NRSV, as you note, translates the initial vav. But it adds an unnecessary "it" after "found". Neither version literally translates the "by the hand of Moses" -- which is particularly odd since the NASB95 went out of its way to translate "sons of Israel" in the same verse. Neither version shows particular fidelity to the text, and I'm calling this a tie. |

1 Chron 6:24 |

Larry, we'll blame your randomizer for this verse. Tie. | Tie. |

Cumulative Scores: |

Torah: 1 (NRSV) - 6 (NASB95) - 3 (tie) |

Torah: 2 (NRSV) - 4 (NASB95) - 4 (tie) |

To read more click the following links:

NASB vs. NRSV

NASB vs. NRSV Round 1: Torah

NASB vs. NRSV Round 2: Nevi'im

Comments where these discussions are taking place

NASB vs. NRSV Round 2: Nevi'im

The first round of verses from the Torah proved my original suggestion regarding the NASB. Surprisingly though (to me), this second round has proved much more even between the NASB and NRSV. Here are the results:

| Reference | Larry's Evaluation | Rick's Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

Josh 18:21 |

Bnei as "sons of" is captured in the NASB95 -- this is the more literal version here. [Why the NRSV didn't use Benjaminites here is not clear; much better is the NJPS: "And the towns of the tribe of the Benjaminites, by its clans, were: Jericho, Beth-hoglah, Emek-keziz."] |

Larry, I am in agreement that Josh 18:21 is more literal in the NASB. Not only does the NRSV leave out sons, it also leaves out the “and” (for the Hebrew vav) before the last two cities listed. Although these aren’t necessary for good English and the NRSV reads better, the NASB is more word-for-word literal in this instance. |

2 Sam 1:3 |

It is funny that the NASB95 insists on the word order "from where do you come" while filing to put "And said to him" first in the sentence or inverting "From the camp of Israel have I escaped." Both the NASB95, despite liberties with the text, retain the somewhat confusing "and he said to him." Still, the word order in both is unnecessarily confused compared with the original, so I am calling this a tie. Note the KJV is far more literal than both of these versions. | I’ll have to disagree here. I don’t see how awkward word order creates a tie. Plus, the NRSV does not reflect the initial vav of the verse (captured in the word “then” in the NASB), nor the vav that introduces the quotation. That makes at least two places where the NASB is more literal. |

2 Kings 4:32 |

The NASB95 does translate v'hinei as behold, but why does it omit the "and"? Even worse, why does it put an unnecessary "and" before "laid on" which is not in the Hebrew "mat mushkav." In the KJV the "and" is correctly marked as an interpolated word. This could be a tie, but I think the NRSV is slightly more true to the Hebrew here. | Larry, I agree that neither is fully literal here, but I’ll opt for a tie because I don’t see how the NRSV is any more literal than the NASB. To pick up on a couple of your comments, I debated internally whether “lad” was more literal than “child” for na’ar. Although na’ar can mean "male" or "female" according to the context, here it is clearly male. Personally I prefer translating words like this according to the context of the gender, so I would prefer “lad” or perhaps better, “boy,” but I can’t fault the NRSV simply because I would have translated it differently. Technically, “child” is not incorrect. Also, I would guess that the reason “and” is added before “laid on” is because the verse literally reads “the boy was dead laid/lying on the bed.” A comma between dead and laid would have sufficed, but by the NASB’s own rules, “and” should have been in italics. So again, I’m going to call this a tie. |

2 Kings 17:23 |

The NASB95's "carried away into exile" is more complex than the literal Hebrew and does not communicate the idea of golut from the simple word va-yigel. One might think that "spoke through" is more literal than "foretold", but the literal sense of diber is in both phrases. In this case, the NRSV is more literal. | I agree, the NRSV is closer to the Hebrew here. |

Isa 24:15 |

The NASB95 gives the literal meaning of "east", but changes the word order rather dramatically, while the NRSV tracks it accurately. Nonetheless, the NRSV unnecessarily repeats the English word "glory/glorify" while it only appears once in the Hebrew. I'm calling this a tie, with neither version as literal as it could be. Note, that the KJV is far more literal here and superior from a literary perspective. | Larry, I don’t disagree with your general points about the rendering in these verses, and all things equal I would call it a tie as well. However, two issues make me lean the scales in the favor of the NASB. First, the NASB offers a more literal rendering of “region of light” in the notes in place of “east.” Second, in the second line, the NRSV duplicates the first line’s use of khvd by adding the word “glorify.” While this makes for smoother reading, it does not match the literalness of the NASB. |

Isa 64:11 |

First, note that this is a place where the Hebrew and traditional Protestant bible have different verse numbering. I've used the Protestant numbering here.

First we notice the gender difference, the NASB95 "fathers" and NRSV "ancestors" for "avoteinu." The NASB95 is more literal here, and I was a little surprised to see no footnote in the NRSV. The NASB95 puts "by" in italics, but somewhat unnecessarily, since a literal reading of lisrefat would be "for burning of" rather than "burned by." I will remark here that I find the NASB95's arbitrary use of italics somewhat disturbing -- it should only be used for words added to the English translation, but it seems to be rather inconsistently used for that purpose (many words added to the English translation are not italicized.) Both "our precious things" and "our pleasant places" are legitimate translations of machmadeinu and I don't find the ruin/ruins distinction significant here. So in this case, I count the NASB95 as more literal. |

I’m in essential agreement here that the NASB is more literal. However, on a minor note, is “our pleasant places” a legitimate rendering for machmadeinu? I can’t find any similar gloss in the HALOT or the BDB unless I overlooked it. |

Isa 66:11 |

These are very close. Both are using a modern interpretation of miziz which compares it with the Akkadian zizu or the Arabic zizat which means udder. However, kvodah is best translated as glorious, so the NRSV has a slight nod here. | I agree with the assessment that the NRSV is more literal, not only for what you mention, but also note that the NASB changes the singular shod to a plural [“breasts”]. |

Jer 31:39 |

Almost identical; the NRSV gets a slight nod for translating v' as "and". | Agreed, NRSV is slightly more literal for translating the two instances of the Hebrew vav. |

Ezek 43:15 |

Ignoring the rather odd alternative translation proposed by the NASB95 in the footnotes, the major differences are the omission of the initial "and" and the interjection of the bridging phrases "shall be" and "shall" in the NASB95. The first is marked as added words (using italics), the second is not, although I'm not convinced this is necessary. Similar to the last verse considered, the NRSV gets the nod solely for translating the initial v'. However, if Rick calls these ties, I'll understand completely. | No, I won’t call this a tie. As in the last instance, the NRSV is more literal. |

Jon 4:5 |

Sukah is normally translated as "booth", but "shelter" is equally valid. I would have chosen "booth" to remind the reader of the connection with the Festival of Booths, but I regard the variation as insignificant. "Ad asher" is best translated as "till", so the NASB95 gets a slight nod here. Strangely, in this case, the NRSV translates the v' in vaya'as but not in vayeshev, while the NASB95 does the opposite. |

I will agree to the tie only because the NASB offers a literal translation of city in the footnotes. Otherwise, in response to the issues you’ve already mentioned, I would have been willing to give the nod of literalness to the NRSV. Translating both instances of 'ir creates an odd-sounding redundancy in English, but it is more literal. But nevertheless, I’ll agree to a tie; although again, I almost gave this to the NRSV. |

Cumulative Scores: |

Torah: 2 (NRSV) - 4 (NASB95) - 4 (tie) |

Torah: 1 (NRSV) - 6 (NASB95) - 3 (tie) |

To read more click the following links:

NASB vs. NRSV

NASB vs. NRSV Round 1: Torah

Comments where these discussions are taking place

NASB vs. NRSV Round 1: Torah

Now, I should point out a couple of things. Although we do discuss accuracy of translation, that is not what we are trying to determine. We are strictly attempting to determine which translation was more literal in its rendering of the original text. Having used both translations quite a bit in the past, I am still confident that the NASB is much more literal than the NRSV, but we'll let the chips fall where they may. Further, I've written before that literal is not always to be equated with accuracy. I've already stopped using the NASB in public because of its literalness. I would think that if the NRSV was more literal, that would not really be a good thing.

Our evaluations follow below. Larry began tackling this much sooner than I had opportunity, so although I made my evaluations without his findings in front of me, my responses are in reaction to what he had already posted. You can read our dialogue in the comments of the post NASB vs. NRSV to see the original context for what is below including Larry's rebuttal to my evaluation of Deut 1:34.

| Reference | Larry's Evaluation | Rick's Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

Gen 2:8 |

The NASB95 and NRSV are quite close, but have these differences: The NRSV correctly includes the initial vav ["and"] and the NASB does not. The NRSV keeps together the phrase gan b'ayden ["garden in eden"] and adds afterwards adds miqedem ["in the east"] so in this verse, the NRSV is more literal |

Larry, you are right that these verses are very close. The NRSV does retain the initial vav which is very interesting considering most of these were removed in the 1995 revision for sake of readability (along with unnecessary kai/and in Mark’s Gospel, demonstrating that he might’ve been writing in Greek, but he was thinking in Hebrew/Aramaic). I’d be interested to know how many of these are retained in the NRSV vs. the NASB.

You’re also right that the word order is closer in the NRSV than the NASB, which I had to admit was surprising when I saw your initial analysis. I concur that the NRSV is more literal in Genesis 2:8. |

Ex 18:6 |

The Hebrew begins vayomer ["and when one told"]. In this case, the NASB95's footnote slightly more correct (although not as literal as it could be.) Also the final imah ["with her"] is only in the NASB95. So in this case, the NASB95 is more literal. | Again, in agreement here. It’s the NASB’s translation of the final phrase ‘immah/with her that pushes it to being slightly more literal. Although the NRSV’s elimination of this unnecessary phrase (in English) certainly makes it more readable. |

Ex 30:26 |

In this case, only one word distinguishes the NASB95 and NRSV. The word, ha-edut, is given three english definitions by the NRSV (which also gives the original Hebrew word). One of the NRSV's translation words is the one used by the NASB95. In this case, I regard the NASB95 and NRSV as exactly equally literal. | Agreed that both are equally literal. The NRSV’s note is more helpful though. I think we’d both agree that the NRSV has better notes that most current English translations. |

Ex 38:25 |

Once again, the NRSV and the NASB95 are very close. NRSV has "of", NASB has "from" -- both are valid interpretations of the Hebrew. NRSV has "measured by" and NASB95 has "according to" -- in both cases for the b' in b'sheqel haqodesh. I think that both are equally valid. However, "mustering" is indeed the more literal translation, and since we are counting footnotes, in this case, I must say that the NASB95 is slightly more literal. | Again agreed that the NASB is more literal here, but only slightly so. On an interesting stylistic note, I find it odd that the numbers are spelled out in the NRSV. When I teach my writing classes at IWU, the general rule I teach is to spell out numbers ten or less and use numerals for anything greater because this is easier to read. I generally find the NRSV to be an easier read than the NASB, and I’m surprised to notice for the first time how large numbers are presented. |

Lev 1:7 |

The only difference his "priest Aaron" vs. "Aaron the priest". Here, Aaron the priest better tracks "Aharon ha-kohen" so the NASB95 is more literal. | Agreed that the NASB is more literal, but barely and insignificantly so. |

Num 8:24 |

Here, both verses are more literal in parts. For the NASB95, "he" correctly captures the singular in "yabo" and also "and upward" is found in the Hebrew. But the word order "do duty in the service" is more correct than "perform service in the work" [ "tsava bavodat"] So, I am calling this a tie. | For the first time, I am going to disagree with your evaluation. Although I do agree with the two different literal phrasings in each translation, I would suggest that “enter” for the Hebrew bo’ is more literal than the NRSV’s “begin.” Therefore, I would suggest that cumulative with the other issues you point out, the NASB is more literal. |

Num 10:9 |

The NRSV and NASB95 are almost identical in this case, but both are in error, because the initial v'chi tavo'u milchmah is ambiguous and unclear (I would have translated it when you are at war.) So this is a tie, with both versions falling short. | I’ll hesitantly side with you that we have a tie here. I wonder though, aside from literalness if “attacks” in the NASB is not a better rendering than “oppresses” for tzrr. If I’m reading the HALOT correctly, warfare is in mind in this word, not the less specific idea of oppression. I want to side with the NASB for being more literal here, but I’m not 100% decided, so therefore I’ll go with a tie. |

Num 25:15 |

The NASB95 translates "umot beit av" literally here, so the NASB95 is more literal. | The NASB is by far more literal here, including it’s use of footnotes. So we are in agreement here. |

Deut 1:34 |

Both the NRSV and NASB95 fail to accurately capture "et qol divreichem." NASB95 attempts to caputre this with "the sound of your words" but sound is not quite right here. NRSV simply translates "your words" but fails to capture the intensifier with the meaning "your loud words" or "your purposeful words." The NASB95 translates v'yishava as "and took an oath" while the NRSV's "and he swore" -- here, clearly, the NRSV finds a single word solution and accurately captures the meaning. However, the NRSV fails to translate the final le'omor. So in this case, we have another tie -- neither version is particularly literal. | Larry, I don’t see how you can say we have a tie here. Et qol divreichem is literally “the sound/voice of your words” so the NASB’s rendering is quite literal—and more so than the NRSV--even if it doesn’t carry the meaning completely across. But that shouldn’t matter because we’re talking about literalness in this comparison, not accuracy of meaning. If we’re going to do that, we stepping into dynamic equivalency, which I have no problem with, but that wasn’t the purpose of this comparison.

Further, the NASB renders le’mor as “saying,” which although redundant in English is literal to the Hebrew text. The NASB is undoubtedly more literal in this verse to me. So we disagree here. |

Deut 13:6 |

The NASB95 re-arranges the verse, putting entices in the middle; the NRSV also slightly re-arranges the verse putting secretly near the front. But the NASB95, by moving the first word, does the most violence to the verse. Also, the NRSV here gives more literal textual variants. So I would say this is close, but the NRSV is slightly more literal. Note that Fox's translation is far more literal here (actually, this entire analysis has clearly indicated to me that both the NASB95 and NRSV fall short in contrast with Fox, which closely tracks the Hebrew):

|

I’m going to call this a tie. Although I would decidedly say that the translation from Fox is more literal, I don’t see any harm in the NASB’s moving the first verb which is commonly done in translations because word order in Hebrew doesn’t always make sense in English. The textual variant provided by the NRSV doesn’t have anything to do with the way the text has been rendered. As I said, I’m calling this one a tie, so we disagree here. |

Cumulative Score: |

2 (NRSV) - 4 (NASB95) - 4 (tie) |

1 (NRSV) - 6 (NASB95) - 3 (tie) |

So...round one goes to NASB.

NASB vs. NRSV

We use the most current versions of the NRSV and NASB (in particular, the 1995 edition of the latter). Our comparison is the standard Masoretic text and the NA27. For the purposes of this comparison, we do not consider the apparatuses of the original text. We strive to use the simplest "plain meaning" of the source text, for example, translating idioms literally rather than by meaning. We do not consider poetic issues such as prosody, rhythm, alliteration, multiple meanings but only plain meaning. If there is some point which calls for theological interpretation, we use the simplest and most straightforward interpretation.

We use a random number generator to pick 10 verses each at random from each of the following sections of the Bible, for a total of 50 verses:

Torah

Nevi'im

Kethuvim

Gospels+Acts

Epistles+Revelation

We count footnotes in the translation if they include some indication of "literal meaning" or "Hebrew original" etc. We evaluate the resulting 50 verses to see if the NASB or NRSV are equivalent in their degree of literal, if one translation is more literal than the other, or if they are incomparable for some reason (for example, they are both literal but in different parts of the verse). If we agree, we count it as a point, if we disagree, we briefly explain why. If either of us feels the random selection of verses was not representative, we draw additional verses from the section(s) in question. At the end, we see if we have a general consensus or not.

I'm sure the results will be very interesting, although I've already stopped using the NASB publicly because of its literalness. If the NRSV were to prove even more literal, I don't think that would be a positive aspect for it. But I stand behind my initial statement. I've used the NASB since 1980 and the NRSV was the primary translation I used in my M.Div papers from 1991 to 1994. The NASB is definitely more literal as a whole.

TNIV More Literal Than the NASB?

I thought about this last week as I was preparing for our Nehemiah Bible study on Sunday. Consider Neh 9:16--

“But they, our ancestors, became arrogant and stiff–necked, and did not obey your commands.” (TNIV)

“But they, our fathers, acted arrogantly;

They became stubborn and would not listen to Your commandments.” (NASB)

The phrase stiff-necked (NIV/TNIV) or stubborn (NASB) comes from the Hebrew phrase wayyaqshu ’et-‘orpam (I'm transliterating the Hebrew because sometimes the reverse-letter unicode Hebrew that I've used in the past doesn't display correctly in every browser). This phrase refers to a hard/stiff (qashah) neck (oreph) and alludes to the beast of burden who doesn't submit to his master's instruction to turn one way or another, but stiffens its neck and refuses to submit. In a sense, the Levite speakers in Nehemiah 9 are claiming that their ancestors behaved like stubborn animals in response to God's commands.

So here, the NIV/TNIV translates the Hebrew idiom literally while the NASB translates the meaning of the two-word phrase with the one word, stubborn.

Of course, there are lots of examples like this between these translations, but the most profound just might be 2 Tim 3:16--

“All Scripture is God–breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness,” (TNIV)

“All Scripture is inspired by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, for training in righteousness;” (NASB)

The NIV/TNIV's rendering of God-breathed and the NASB's inspired come from the Greek word θεόπνευστος meaning literally "breathed of God." The context of 2 Tim 3:16 refers to the divine nature of the Holy Scriptures. Paul chose this word, which is also found in non-biblical Greek writings, to describe the origin of Scripture. θεόπνευστος essentially means "inspired by God," but it is rendered literally in the NIV/TNIV and dynamically by the NASB.

Now obviously, overall the NASB is more literal than either the NIV or TNIV. But I point this out because we need to keep in mind that the labels attached to Bible translations such as "literal" or "idiomatic" are not always rigidly true. The NASB is fairly consistent in its literal renderings, but this is not always the case (compare for instance the NASB and TNIV's translation of πορνεία in 1 Cor 5:1--the TNIV is much more precise). And often detractors of the NIV and TNIV claim that these translations are too interpretive. Again, they can be more literal in some cases than the translations that have a reputation for such.

All in all, a translation like the NIV or TNIV is neither wholly formal equivalent or wholly dynamic. The translators attempted to strike a halfway point. This is also essentially the same method used in the HCSB (called "optimal equivalence"). In the end, these kinds of translations get the best of both worlds--the preciseness of the formal and the readability of the dynamic.

Literal Is Not More Accurate If It's Unintelligible

One of the points that I had disagreed with Kevin on had to do with the claim often made by proponents of the ESV this their translation of choice is literal like the NASB but more readable. In my examination, I find this to be a highly exaggerated claim. My feeling toward the ESV is that it is weakened by its reliance on antiquated phrasings in the RSV (upon which it was based) and there's really no excuse that these have never been corrected. I often point to two representative verses as proof of my disbelief that the ESV is more readable than the NASB. One is Matt 7:1:

“Judge not, that you be not judged.” (ESV)

“Do not judge so that you will not be judged.” (NASB)

Try reading the ESV rending of Matt 7:1 out loud. The ESV employs an awkward use of a reverse negative ("Judge not"). The problem is that no one I know of speaks this way on a regular basis unless you want to count Yoda in the Star Wars movies (and he lived a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away). Even with the reputation that the NASB has for literalness and even woodenness, its translators had the sense to remove a great many of its uses of reverse negatives in its 1995 update (although some remain). Granted, you can find reverse negatives in just about any translation, but I would suggest that the ESV has more than any modern translation of the last 15 years or so because they were never removed when updating the RSV. This makes it less readable in these verses than the NASB and just about any other translation.

Another example I point to regarding the ESV's exaggerated claim of readability is a verse like Heb 13:2:

“Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.” (ESV)

“Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by this some have entertained angels without knowing it.” (NASB)

Just because a word is in the dictionary does not make it standard English. The ESV's retention of the RSV's archaic and antiquated unawares is downright odd. I can't imagine anyone outside of perhaps a hillbilly community still using unawares today. These are merely two examples, but they represent a great many more. Yes, there are some places in which the ESV is more readable than the NASB, but the ESV is incredibly uneven because of its dependence on antiquated words and sentence structures in the RSV. My goal is not to knock the ESV so much as to challenge the outrageous claims of some of its proponents.

In response to the above two verses I suggested, Kevin said that the TNIV had flaws as well and gave Rom 1:3 as an example:

In Rom. 1:3, it changed it to "regarding his Son, who as to his earthly life was a descendant of David." In the ESV ... it uses "flesh." I think Paul wanted to use "flesh" to express the idea of "body." The TNIV might be a bit too loose in using "earthly life." It's only a possible intended meaning but not necessarily what Paul actually wanted to express in using "flesh."

While I do acknowledge that all translations have weaknesses, I personally don't see a problem with Rom 1:3 in the TNIV. The rendering "according to the flesh" [κατὰ σάρκα] in the ESV (and a number of other formal equivalent translations) while certainly reflecting a literal rendering, really doesn't communicate that much. Although there's part of me that likes a translation that renders σάρξ as "flesh" because it triggers in my mind the underlying Greek word, I know for a fact that for the average church-goer and for every non-church-goer, "according to the flesh" is a meaningless phrase. Most of my readers here know what "according to the flesh" means because they have the background for understanding it. But try to step outside your learning and think about the phrase from the ESV: "concerning his Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh." That is just unintelligible to those who don't have a knowledge as to what the phrase means because it reflects an idiom that is not in current English usage (especially outside the church). At best, use of "flesh" in this sense is insider church language, and I would still suggest that many sitting in an average Sunday School class couldn't give you an accurate explanation.

Obviously all Paul is saying is that Jesus was a descendent [υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ τοῦ γενομένου ἐκ σπέρματος] of David only in regard to his earthly body. He's being very careful not to imply that David actually came before Christ because in reality, Christ is eternal. Therefore, the TNIV's rendering "who as to his earthly life was a descendant of David" fully communicates Paul's intention. Yes, the ESV is more literal in the strictest sense, but in way similar to the point I was trying to prove in "Grinding Another Man's Grain," if literal is unintelligble, it is certainly not accurate.

Also note that the TNIV indeed has a footnote to this verse that says "Or who according to the flesh" which I feel is an INCREDIBLY responsible way to handle the verse. It gives a very readable rendering in the text and a literal rendering in the footnote. The best of both worlds, wouldn't you say?

Now on a related note, I've been mildly reflecting on Mark Driscoll's announcement that Mars Hill Church (Seattle, Washington) would replace the NIV with the ESV as their primary translation. Now on the face of things, that's perfectly fine with me. Every church should use the translation that best works in their context. They have a right and obligation to sort through such choices. My problem lies not with the choice, but with Driscoll's rhetoric as he elevates the ESV over translations he considers inferior.

As one of his reasons for choosing a new translation, Driscoll states "The ESV upholds the truth that Scripture is the very words of God, not just the thoughts of God." The context of the statement comes from two paragraphs earlier in which he writes, "we should transition from the NIV (more of a “thought-for-thought” translation) to the English Standard Version (ESV, more of a “word-for-word” translation) as our primary pulpit translation." In my opinion the statement made by Driscoll which I have highlighted in bold above betrays a lack of understanding of the differences between formal and dynamic equivalent translation methods.

However, this is case in point again to the fact that the ESV cannot stand up to the claims made by its proponents. Take for example Rom 1:3 discussed above. The ESV does not translate that verse literally throughout. In fact, it doesn't translate a significant Greek word found in the original text at all.

Rom 1:3, [περὶ τοῦ υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ τοῦ γενομένου ἐκ σπέρματος Δαυὶδ κατὰ σάρκα] in English literally reads "concerning his son who was born [γενομένου] from the seed [σπέρματος] of David according to the flesh."

Therefore, the ESV isn't entirely literal in this verse either. The ESV's rendering of "concerning his Son, who was descended from David" completely omits either γενομένου or σπέρματος. I would have suggested they are leaving out the former, but according to the ESV Reverse Interlinear, it's the latter. Regardless, if, as Driscoll says, the "ESV upholds the truth that Scripture is the very words of God, not just the thoughts of God," why then does the ESV offer a "thought-for-thought" (dynamic equivalent) translation for "γενομένου ἐκ σπέρματος Δαυὶδ" in Rom 1:3? Is the ESV shortchanging the word(s) of God? Is not every single word important? Is σπέρματος not inspired? According to Driscoll's own standards for why he chooses the ESV, the ESV itself cannot stand up. (Also compare with the NASB rendering of Rom 1:3 in which both Greek words are translated.)

Now, if you've read this blog for any amount of time at all, you'd know that I would have no problem with the ESV's rending of "concerning his Son, who was descended from David" any more than the TNIV's "who as to his earthly life was a descendant of David." Translation is more complex than simply looking up the definition of a Greek word and supplying an equivalent English word. Suggestion of such by Driscoll and others demonstrate a significant naiveté on the subject of translation method.

My contention is not with the ESV. But I do have great problems with the inaccurate rhetoric that I often hear from proponents and endorsers of this translation. I have favorite translations, and I have written about a number of them on this blog. While I talk of their qualities that I like and appropriate uses for them, I go out of my way to try to do so without needlessly putting down other versions of the Bible. I've probably been harder on the ESV on this blog than on any translation, but usually it's been in a context of addressing the audacious and often fallacious claims made for it by ESV supporters. This idea that literalness equals greater accuracy or literalness equals greater faithfulness to the original text is pure nonsense if the rendering is so literal that the author's intent and meaning is unintelligible to readers and hearers. Antiquated vocabulary and sentence structure do not give a translation greater authority--it merely limits readership in an contemporary setting.

The New Testament was written in Koiné Greek--the common trade language of the day--a language accessible by the masses. If a Bible version uses renderings that are not understandable to the masses, renderings that sound like they were written in any previous generation or written in some highly exalted form--regardless of how literally accurate--then that translation is not in keeping with the spirit or the manner in which the New Testament was written.

Grinding Another Man's Grain

Consider, for example, a passage I came across today while preparing a talk I'll be giving tomorrow morning to the men at my church. Since we won't be in mixed company, I'm going to address the growing issue of internet pornography. I'm using Job 31:1-4 as my opening text. But in looking at that passage in the context of the whole chapter, I was struck by the way various translations handle Job 31:9-10:

| Job 31:9-10 | ||

|---|---|---|

NASB |

TNIV |

NLT |

| If my heart has been enticed by a woman, Or I have lurked at my neighbor’s doorway, May my wife grind for another, And let others kneel down over her. |

If my heart has been enticed by a woman, or if I have lurked at my neighbor’s door, then may my wife grind another man’s grain, and may other men sleep with her. |

If my heart has been seduced by a woman, or if I have lusted for my neighbor’s wife, then let my wife belong to another man; let other men sleep with her. |