ἀλλόφυλος and Psalm 151

PSALM 151 |

||

LXX |

NETS |

NRSV |

1 οὗτος ὁ ψαλμὸς ἰδιόγραφος εἰς Δαυιδ μικρὸς ἤμην ἐν τοῖς ἀδελφοῖς μου 2 αἱ χεῖρές μου ἐποίησαν ὄργανον 3 καὶ τίς ἀναγγελεῖ τῷ κυρίῳ μου 4 αὐτὸς ἐξαπέστειλεν τὸν ἄγγελον αὐτοῦ 5 οἱ ἀδελφοί μου καλοὶ καὶ μεγάλοι 6 ἐξῆλθον εἰς συνάντησιν τῷ ἀλλοφύλῳ 7 ἐγὼ δὲ σπασάμενος τὴν παρ᾿ αὐτοῦ μάχαιραν |

1 This Psalm is autographical. I was small among my brothers 2 My hands made an instrument; 3 And who will report to my lord? 4 It was he who sent his messengerd 5 My brothers were handsome and tall, 6 I went out to meet the allophyle, 7 But I, having drawn the dagger from him, |

1 I was small among my brothers, and the youngest in my father’s house; I tended my father’s sheep. 2 My hands made a harp; 3 And who will tell my Lord? 4 It was he who sent his messenger 5 My brothers were handsome and tall, 6 I went out to meet the Philistine, 7 But I drew his own sword; |

Our Bible study at church last Sunday came from 2 Samuel 5-7. The curriculum we use drew upon a theme, “When Assessing One’s Work.” With that theme in mind, and because the chief figure in 2 Samuel is David, I thought that I might introduce my Bible study class to Psalm 151. As I suspected almost everyone in my class was unfamiliar with this Psalm as it is not accepted by Jews, Protestants or Catholics, but is considered canon by the Orthodox Church. Traces of this Psalm, found in the Septuagint, have been discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls, so its origin is probably Hebrew after all.

Unfortunately, my bright idea to use Psalm 151 was practically an afterthought to my preparation of the lesson from 2 Samuel. In fact, as I was walking out the door, I grabbed by copy of the New English Translation of the Septuagint (NETS) and added it to the stack of volumes I was already carrying. I had not looked at Psalm 151 recently, but was merely drawing off my memory of its theme and content.

At our church we have our worship service before our time of Bible study. After getting a bit settled, I opened up my copy of the NETS that I had grabbed as I was leaving the house to take a look at its rendering of Psalm 151. The NETS, released only last year, is the most current English translation of the LXX. Everything seemed fine until I got to v. 6:

I went out to meet the allophyle, and he cursed me by his idols.

Allophyle? What’s an allophyle? I had not read Psalm 151 in a while, but I knew I didn’t remember seeing this particular word in other translations. Now, if you look above at my chart containing the Greek text, you’re better off than I was Sunday morning. I didn’t have a copy of the Greek text with me. And I couldn’t figure out what an allophyle was immediately from the context.

I pulled my iPhone from my pocket, and tried looking up the word in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary app. No dice. The word allophyle was not to be found. I nudged Kathy and pointed to the word, asking if she knew what it meant. She asked for the reference, and I told her “Psalm 151:6.” She picked up her Bible, but then rolled her eyes, put her Bible back down and ignored me, realizing that Psalm 151 was not going to be in her copy of the New Living Translation.

I tried to figure out meaning based on the derivation of the word. I assumed it was created from two Greek words, and correctly guessed that allo- came from ἄλλος/allos, meaning “other” or “another.” But I went in the wrong direction with -phyle. I incorrectly guessed that perhaps somehow it came from φίλος/philos, meaning “beloved” or “dear.” We get words like bibliophile (lover of books) from this word.

But this made no sense. David went out to meet his other lover? And then cut off his head? Well, I knew from both memory and context that the individual in question was Goliath, so I knew something was off from my guess. I ran a search on my iPhone for Psalm 151 on the internet and found the NRSV translation of “Philistine.” That didn’t explain my immediate question, but it did give me another way to read the verse during our Bible study.

Once I was home and able to look up the passage in the Greek of the LXX, I realized that in using allophyle, the NETS essentially transliterates ἀλλόφυλος/allophulos, a word often translated Philistine or foreigner based on the context. I freely admit that I was not familiar with the word as it only occurs once in the New Testament:

“And he said to them, “You yourselves know how unlawful it is for a man who is a Jew to associate with a foreigner (ἀλλόφυλος/allophulos) or to visit him; and yet God has shown me that I should not call any man unholy or unclean.” (Acts 10:28, NASB)

How does one get foreigner, Philistine or even Gentile (as some translations render it) from the word? Well, as I said, I was wrong about my guess regarding -phyle. It didn’t mean “beloved” but rather came from the Greek word φυλή/phule (from which we get words like phylum), meaning “race” or “tribe.” So ἀλλόφυλος/allophulos literally means “other race” and thus foreigner.

On p. 246 of the NETS, there is passing reference to peculiar habit of the Old Greek to translate “פלשתים ‘Philistine’ as (ὁ/οἱ) ἀλλόφυλος/-οι ‘allophyle(s),’ first seen in the book of Judges (3.3, 31; for a total of 20x), rather than the transliteration φυλιστιμ (‘Phylistim’ ) found already in Genesis (8x), Exodus (2x), Iesous (Joshua) (1x), Judges (6x) and Sirach (3x).” However, there’s no explanation why the NETS chooses to transliterate the word in question as allophyle. My only guess is that this is done to designate when the the LXX is doing the same, although the word occurs many other times in contexts simply meaning “foreigner” and the NETS does not transliterate it in these instances.

So now there’s only one other question. How common is the English word allophyle? As mentioned earlier, it wasn’t in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, and even now as I write it on my computer, a red line underscores it. I wondered if perhaps allophyle is used in biblical or historical studies so I ran a search for it in literally thousands of reference books and journals in Accordance. The only hits I received for the word came from the NETS. Even running a Google search, if limited to English hits, results in only 95 websites, and most of these are questionable regarding any solution to my curiosity.

So, help me out. Have you come across the word allophyle anywhere in English besides the NETS? If you have, please list the source in the comments.

Keeping One's Emotions in Check: Psalm 4:4 in the RSV/ESV

I was teaching the imperative mood in my Greek class today when a question came up about an example I used. To illustrate the idea of an imperative granting permission, I offered the same verse as our textbook, Eph 4:26—

ὀργίζεσθε καὶ μὴ ἁμαρτάνετε

[You may] Be angry and/but do not sin

One of my students asked about the original OT passage that Paul quotes. He wanted to know if it was an imperative in the LXX. It’s true that the passage quotes Psalm 4:4 (4:5 in the LXX/BHS). And although I didn’t know the answer off the top of my head, it was easy enough to find out. So I threw an Accordance window onto the projector screen.

We looked up the passage in the LXX, and sure enough it was exactly the same down to the letter. The same imperative form for ὀργίζω (to be angry) was used in the passage: a present passive imperative, 2nd person plural. Someone looking in his own copy of the Bible noted however, that the NASB did not use “Be angry,” but rather Tremble. I suggested that often such a disagreement occurs because the NT writers usually quoted the LXX, but our modern translations are based off the Hebrew text and sometimes variations occur. Then I threw up a few English translations for comparison, most of which had the same or a similar idea as the NASB. But when I opened a pane with the ESV, I was surprised to see that it said, “Be angry... .”

Having spent enough time on this issue, I went back to our lesson. However, I was curious enough to look at this issue after class. As I was to confirm, the Hebrew for Psalm 4:4/5 is not a word that specifically means to be angry. The Hebrew word used 4:4/5, rigzu, is the qal imperative form of rgz. My Hebrew is in the rustier section of my language toolbelt, but I can still read a lexicon. And according to the HALOT, the qal form of rgz means (1) to tremble, be caught in restless motion, (2) to tremble with emotion: from terror, (3) to come out quaking with fear, (4) to get excited. Although it's not my desire to try to defend the LXX's choice of ὀργίζω for rgz, I can question the ESV's use of "Be angry" since the translation claims to be based on the Hebrew OT, and certainly not the Greek.

I should point out that the ESV does include an alternate translation to "Be angry" in the footnotes: "Or Be agitated." Is Be agitated a better translation? Well, according to the HALOT, only if rgz takes the hifil form (which it does not in Psalm 4).

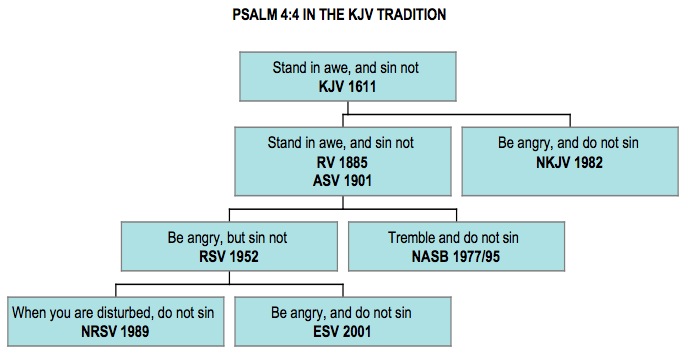

My first hunch was simply to assume that the ESV translators were once again engaging in the questionable practice of trying to make the OT text conform to NT quotations, something that doesn't always work for reasons I've stated above. However, rather than jump to any sudden conclusions, I decided to check out other translations in the Tyndale tradition, especially the ESV's immediate predecessor, the RSV. After checking with the Tyndale translation, I was reminded that there is no Tyndale version of the Psalms (at least that's survived), so it's probably more accurate to say in the KJV tradition. The chart below demonstrates the variations of Psalm 4:4 in all translations that trace their lineage in one way or another to the KJV.

It's very interesting that while the KJV followed the Hebrew, it was the RSV that first departed and followed the LXX instead. I find this highly ironic since the RSV was heavily criticized by conservatives for following the Hebrew reading in Isa 7:14 instead of the LXX which harmonized with Matt 1:23. So I believe it's fair to say that initial fault does not lie with the ESV, but with the RSV. And I haven't looked at every translation on my shelf, but between the ASV and the RSV, only a couple of translations of any significance stand out: the Moffatt version and the Smith/Goodspeed version. Both of these use tremble. Therefore, as far as I know, it is the RSV that first introduced "Be angry" to Psalm 4:4.

However, the ESV is to be questioned here regardless because the translators have chosen to leave a faulty translation in place for what I can only guess is simply is simply for the sake of artificial harmonization. This follows one of my primary problems with the ESV--that the revisers did not update the RSV enough. Many of the awkward renderings or simply less-than-adequate translations found in the ESV are simply leftover baggage from the RSV.

That the ESV, which was moderately revised again earlier this year, has retained "Be angry" only suggests to me the original assumption I made that the handlers of this version wish to create a direct correspondence, a harmonization, between the OT text and the passages where it's quoted in the NT. This is problematic, though, when it no longer accurately reflections the meaning of the OT texts such as is the case here. Even the alternate translation, Be agitated would be closer to accuracy, but as is often the case with the ESV, the more accurate rendering is in the footnotes and a more "traditional" (even if inaccurate) rendering is in the main text (see for example, the ESV's consistent translation of ἀδελφοί/adelphoi in Paul's writings as "brothers" while noting the more accurate translation of "brothers and sisters" in the footnotes: Rom 1:13; 7:1; 8:12; 10:1; 11:25; 12:1; 15:14; 16:14; 1 Cor 1:10; 2:1; 3:1; 4:6; 6:8; 7:24; 8:12; 11:33; 12:1; 14:6; 15:1; 16:15; 2 Cor 1:8; 8:1; 13:11; Gal 1:2; 3:15; 4:12; 6:1; Eph 6:23; Phil 1:12; 3:1; 4:1; Col 1:2; 4:15; 1 Thess 3:7; 4:1; 2 Thess 1:3; 2:1; 3:1; 1 Tim 4:6; 2 Tim 4:21). One wonders why the more accurate translations wouldn't simply be preferred in the main text? Well, evidently because it flies in the face of tradition.

As always, your thoughts are invited in the comments below. For reference sake, here is Psalm 4:4 in a few other translations. The ESV is not to be criticized by itself. The NLT and HCSB both use anger, which is even more surprising for the latter which usually goes out of its way to shun traditional renderings for the sake of accuracy. Of course "tradition" in this case only dates back to 1956 as far as I can tell. The original NIV also used anger, but the TNIV appropriately corrects this with Tremble.

“Be angry and do not sin” [note: Or Tremble] (HCSB)

“Tremble and do not sin” (GWT)

"So tremble, and sin no more" (JPS)

"Tremble with fear and do not sin!" (NET)

"In your anger do not sin" (NIV)

"Tremble and do not sin" (TNIV)

"Don’t sin by letting anger control you" (NLTse)

"Let awe restrain you from sin" (REB)

"Tremble with fear and stop sinning" (GNT)

Review: OUP A Comparative Psalter

A guest review by "Larry"

The psalter includes four versions of the psalms: (Masoretic) Hebrew, (Septuagint) Greek, and two leading translations of each: the RSV for the Hebrew and the New English Translation of the Septuagint (NETS) for the Greek.

The idea for the book apparently came from a German edition by Walter Gross and Bernd Janowski published in 2000.

The Hebrew is from BHS 5th edition (1997) with critical apparatus but without masora parva (the notes in the margins of the BHS). The Greek is from Rahlfs’s 1935 Septuagint. The RSV contains full textual notes (often not reproduced in electronic editions) and the NETS also contains textual notes and two useful longer prefaces. (The NETS is a nice translation, with careful attention paid to literal rendering and gender issues, and I look forward to a complete printed edition soon.)

The numbering of the psalms in the Hebrew uses the traditional (English) numbering as opposed to the original Hebrew numbering. The NETS uses both the English numbering and the Greek numbering. The beginning and ending of each of the five books of psalms are carefully marked. The 151st psalm (included in the Eastern Orthodox psalter) is not included.

There is also a simple cross reference system at the bottom of the right-hand pages. While I find such annotations unhelpful, the page layout makes them inconspicuous and easy to ignore.

Other than textual notes, there is no annotation in the psalter. This is a case where less is more -- any annotation would have probably made this psalter unacceptable to some audience.

The introduction does not explain why the RSV was chosen over the NRSV, but one can guess: the RSV is slightly more literal than the NRSV and is also approved for Roman Catholic liturgy -- while the NRSV has the imprimatur, the gender neutral language has caused the Vatican to ban its use in the liturgy. (The ban on liturgical use of the NRSV was made by Cardinal Ratzinger, who has since become Pope Benedict 16, and was the subject of some conflict between the US Conference of Catholic Bishops.) The NRSV Psalter received special criticism from the Vatican. Similarly, although I have seen (carefully qualified) praise for the RSV from some Eastern Orthodox scholars, the NRSV seems to be much more controversial.

Still, the choice of the NRSV would have been more logical, since Albert Pietersma deviates from the NRSV only when he feels the Greek deviates from the Hebrew.

The page size is generous and there is ample space for making notes. (The paper used is thick, although perhaps absorbent -- I haven't tried writing on it yet.) For those familiar with other Oxford parallel Bibles, such as The Precise Parallel New Testament, this work is about an inch taller and wider.

One thing that surprised me is that Oxford placed the NETS logo on the binding and back of the psalter. Usually, Oxford doesn't put Bible logos on its Bibles (thus the Oxford NLT parallel Bibles do not have the Tyndale logos mentioned recently by Rick in this blog.) The NETS logo is especially ugly and busy, so this was a bit of a graphic design failure. However, as they say -- don't judge a book by its cover.

A printed psalter is more useful than an electronic psalter. First, all of the electronic versions of the RSV I have seen omit notes. Second, most electronic versions (with the exception of the Stuttgart Electronic Study Bible) omit Hebrew critical apparatus. Third, to the best of my knowledge, NETS is not integrated into any major electronic Bible package. Third, observant Jews can't use an electronic device on the Sabbath or biblical religious holidays. Fourth, I find having a computer on is distracting to prayer and prefer to pray out of a written book (and actually, I prefer to study out of a written book as well.) Fifth, as already noted, a printed book allows a person to make notes.

I personally have not spent much time studying the Septuagint, and in a few hours perusing this psalter, I found many interesting changes from the Hebrew. While many of the words in the Greek psalms have ordinary meanings, there are a number which are directly taken from the Hebrews. Some of these are stereotypes – words taken literally from the Hebrew which seem unnatural in the Greek; others are calques – Greek words with Hebrew meanings; and still others are isolates – Greek words derived on morphologically parallel basis as the Greek. In some cases, this produces fascinating contrasts: for example, we can contrast Psalm 7:7 (Hebrew numbering) in the Greek and Hebrew:

קוּמָה יְהוָה בְּאַפֶּךָ הִנָּשֵׂא בְּעַבְרוֹת צוֹרְרָי וְעוּרָה אֵלַי מִשְׁפָּט צִוִּיתָ

RSV: Arise, O LORD, in thy anger,/lift thyself up against the fury of my enemies/awake, O my God; [or for me] thou hast appointed a judgment.

ἀνάστηθι κύριε ἐν ὀργῇ σου, ὑψώθητι ἐν τοῖς πέρασι τῶν ἐχθρῶν μου ἐξεγέρθητι κύριε ὁ θεός μου ἐν προστάγματι ᾧ ἐνετείλω,

NETS: Rise up, O Lord, in your wrath;/be exalted in the boundaries [perhaps at the death] of my enemies;/and* awake, O my* God, with the decree which you issued.

[The asterisks refer to textual notes dealing with alternate textual forms which I omit here.]

Now this is quite a contrast – “lift thyself up against the fury of my enemies” versus “be exalted in the boundaries of my enemies.” And what of the alternative textual rendering of πέρασι as deaths? Well a glance at Psalm 39:5 clearly indicates that this word can refer to the end of human life. But the entire sense of the passage is changed in the Hebrew and Greek.

The Septuagint psalter is thus interesting not only for its differences with the Greek, but as a lesson in translation, seeing how the translator struggled to maintain an almost interlinear translation. And this sort of study is made easy with this text: even if one has weak Hebrew and Greek, the convenient English translations make it especially easy to compare the texts.

In summary, I regard this as one of the most useful parallel Bible works I have seen in a while – especially for those interested in Septuagint studies. The size is a little large for a psalter and the English type is surprisingly small, but the Hebrew and the Greek are clear enough.

For me, reading the psalms is one of the central elements of worship – I regularly read through the psalms aloud in Hebrew. I prefer a psalter with minimal distractions for prayer – so I can concentrate as fully as possible, but for those inclined, I see no reason this psalter could not be used for prayer in Hebrew, Greek, or English.

I hope this psalter is a success and that Oxford considers publishing other Hebrew-RSV-NETS-Greek books from the Hebrew Scriptures. A publication program would be a boon to many audiences: those interested in Septuagint studies, those with strong Greek trying to improve their Hebrew, and those interested in the differences in Jewish and Christian development of the Scripture.

Now Shipping: Kohlenberger's Comparative Psalter

Here is the description from the Oxford University Press website:

The Book of Psalms has occupied a central place in Jewish and Christian worship for millennia. This authoritative volume brings together the Psalms in a quartet of versions that is certain to be an invaluable resource for students of this core book of the Bible. The texts featured in A Comparative Psalter represent a progression of the text through time. The ancient Masoretic Hebrew and Revised Standard Version Bible are displayed on one page, while the New English Translation of the Septuagint and Greek Septuagint are on the facing page. The same set of verses is displayed for all four texts, making it easy to compare have rendered The Modern English versions included in this volume are noteworthy for their fidelity to the ancient texts. The first major translation of the Christian Scriptures from the original languages to be undertaken since the King James Version, the RSV debuted in 1952 to critical acclaim. It dramatically shaped the course of English Bible translation work in the latter half of the Twentieth Century, and remains the Bible of choice for many people. Meanwhile, the New English Translation of the Septuagint is the first work of its kind in a century and a half. This major project brings to the fore a wealth of textual discoveries that help illuminate the Book of Psalms for Twenty-first Century readers.

Readers should note that the New English Translation of the Septuagint (NETS) is a completely different translation from the NET Bible of Bible.org (although the similar names are bound to create continued confusion).

Also, I find it interesting that the RSV was chosen over the NRSV for this volume. I wonder if the RSV is more acceptable to some markets than the NRSV--perhaps the Jewish community? Or perhaps the retention of archaic forms for addressing deity (i.e. thee and thou) without resorting to the KJV was the goal. Nevertheless, Kohlenberger remains king of the comparative texts (an excellent way to study from my perspective).

Look for a review of this volume in an upcoming blog entry. Readers may also be interested in my review of Kohlenberger's Parallel Apocrypha.

HT: Larry in earlier comments.

Remarkably and Wonderfully Made

“For it was You who created my inward parts;

You knit me together in my mother’s womb.”

(Psalm 139:13 HCSB)

Our passage of study in Sunday School tomorrow is Psalm 139. As I was reading through the leader's guide to the curriculum tonight, a couple of paragraphs related to v. 13 stood out:

The second line in this verse is an example of a common characteristic of Hebrew poetry. The second line repeats the first line, but it does so by the use of synonyms. Hence knit me together is a synonym for created in the previous line. In light of the complexity of the human body the verb knit me together generates a mental picture that fits the context as well. Inside the womb, God wove tissue, bone, and sinew to form a living being.

The average adult body consists of approximately 650 muscles, 50,000 miles of blood vessels, and 206 bones. About 20 square feet of skin tissue covers these components in males and about 17 square feet is required in females. A baby at birth is even more complex than an adult. The infant has 300 bones. During childhood 94 of these fuse together.

Contemplating such complexities of the human body and God's awesome creative ability makes one truly exclaim with the psalmist the next verse:

“I will praise You,

because I have been remarkably and wonderfully made.

Your works are wonderful,

and I know |this| very well.”

(Psalm 139:14 HCSB)