Top Ten Bible Versions: The Complete Boxed Set

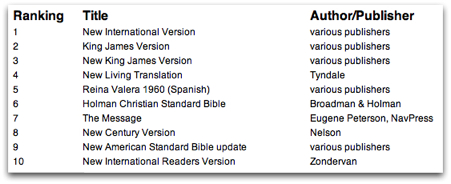

Top Ten Bible Bible Versions: A Few Introductory Words

The Holman Christian Standard Bible (Top Ten Bible Versions #1)

Today's New International Version (Top Ten Bible Versions #2)

Follow-Up Regarding the TNIV

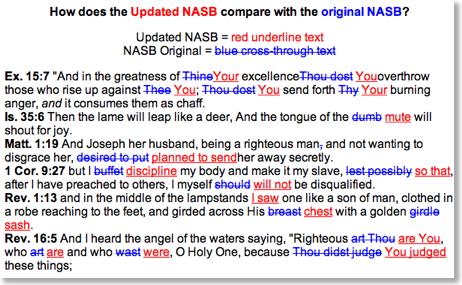

The New American Standard Bible (Top Ten Bible Versions #3)

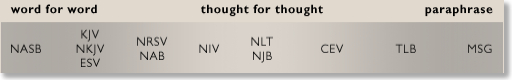

Is a Paraphrase in the Eye of the Beholder?

The New Living Translation (Top Ten Bible Versions #4)

Addendum to my Review of the NLT

Eugene Peterson's The Message (Top Ten Bible Versions #5)

Follow-Up to the Message: What Is the Proper Use of a Bible Paraphrase?

The Revised English Bible (Top Ten Bible Versions #6)

The New Jerusalem Bible (Top Ten Bible Versions #7)

The Good News Translation (Top Ten Bible Versions #8)

The Wycliffe New Testament [1388] (Top Ten Bible Versions #9)

The Modern Language Bible: New Berkeley Version (Top Ten Bible Versions #10)

Top Ten Bible Versions: The Honorable Mentions (KJV, NET Bible, Cotton Patch Version, NRSV)

Top Ten Bible Versions: Final Thoughts (For Now)

Top Ten Bible Versions: Final Thoughts (For Now)

My Own Journey. I've been collecting English translations of the Bible for over two decades and now own a number approaching ninety different translations. Believe it or not, there are still quite a few in circulation that I still do not have (but I have a list!). Two of my most recent acquisitions include an original 1959 edition of Verkuyl's Berkeley Version of the BIble (the first edition with the Old Testament, and the precursor to the edition I reviewed) and the New Testament Transline which was sent to me by Wayne Leman. It may be the most literal modern translation I've seen so far.

Even after taking original language courses in seminary and working these texts into my study practices, I still publicly teach from English translations. I do this for two reasons. A common translation serves as a better common ground base between myself and those in my classes, although I can certainly supplement with my own translation as I need to. Further, my language skills are not good enough yet. I've tried it, and while I can certainly prepare for a focus text, as soon as a question is raised about another passage and we turn there, I run into a word I either do no know or can't remember, and so it's not yet practical for me to use the Greek and/or Hebrew exclusively.

Although I've always celebrated the variety of translations available, up until two or three years ago, I was squarely in the formal equivalent camp in regard to what I used as a primary translation both in public and in private. It was primarily the needs of my audience--the result of my experience teaching both high school students at a private school for about five years and my long term experience teaching adults at church--that made me change my translational tool belt around a good bit. Although I personally preferred more literal translations, especially the NASB, I was never the kind of person I occasionally run into who thought that dynamic/functional equivalence was an illegitimate method of translation. However, like a lot of people, I naively assumed that literalness was always equated with a greater degree of accuracy. However, it was in my experience teaching that I realized if a literal translation does not communicate the message of the original--if the readers or hearers cannot understand it because of its literalness--it is not more accurate; it is less so. I've tried to demonstrate this in a number of my posts with my favorite being "Grinding Another Man's Grain" (also see "This Is Why" and "Literal Is Not More Accurate If It's Unintelligible").

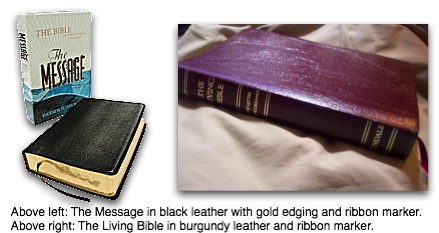

Since I began this series, my own practices have changed somewhat. When I began writing it, I was attempting to make the HCSB my primary translation in public and in private with the TNIV, NLT, and NASB in secondary roles. The HCSB and TNIV have switched places a good bit in much of my use over the last few months. In private I have gone back to taking notes in my wide-margin NASB because I haven't found a suitable replacement edition in any of the more modern translations that I use. This is too bad because I can't legitimately call any translation a primary one for myself until I can take the edition with which I've written my notes in private and teach from that same Bible in public. Nevertheless, when I am asked, I currently only recommend three translations for primary Bibles: the TNIV, NLT and the HCSB.

An Admitted Bias. I admit that I am biased toward newer translations for primary Bibles because they represent not only the latest scholarship, but usually the most current English--although certainly both factors are on a relative scale. That doesn't mean that the older translations are useless. I simply can't recommend them for anything other that secondary purposes--to be read in parallel with a primary translation or to be read for devotional use.

I freely admit that I cannot recommend something like the King James Version, as prominent as it is in Christian and literary history, as a primary Bible. I cannot recommend it for two reasons. The first is that it is based on a deficient textual tradition. This is where my bias for the most recent scholarship comes into play. And although I respect those who hold to a favorable tradition toward the Textus Receptus or the Majority Text, I would politely disagree. In my experience, most of those with whom I've come into contact who favor a TR position often are simply using it as an excuse to justify King James Onlyism. Otherwise, why wouldn't they use the New King James Version? This is certainly not always the case, but I find a lot of people who say they favor the TR, but claim the NKJV as corrupt and practically put the KJV on its own level of inerrancy. Really, I have little patience with this, and simply cannot take such positions seriously.

Secondly, I cannot recommend the KJV to the average church member simply because of my experience in teaching the Bible to adults over the last two decades. Over and over I've seen people struggle with the KJV, often failing to understand what they just read, and stumbling through the text when trying to read it aloud. In many cases I've given these people a modern translations and watched light bulbs go off over their head as suddenly the Bible has new relevance. And I don't know of a worse Bible to give to a child than the KJV. In the end, it simply comes down to a communication issue. I want to see God's Word communicated as clearly as possible

For those who appreciate the KJV on a historical and literary level, we have no argument. I agree that it's place is secure in those regards.

The Bible Wars. It genuinely saddens and even distresses me that adherents of modern translations would fight over which version is supposedly better. I am appalled at some of the rhetoric thrown around toward certain translations often as a smokescreen for promoting another version. Yes, there are certainly translations I recommend over others--I've admitted that. But one thing I've tried very hard to do on this blog is not to promote one version at the expense of another. I really do believe in reading the Bible in parallel. Bible versions are different simply because they often have different goals and purposes. I also acknowledge that certain translations simply connect and resonate with individuals. Sometimes it is a personality factor (and Bible translations have personalities of their own) and sometimes it is for other reasons.

There is some good news though. Sometime near the end of 2006, I set up Technorati and Google search RSS feeds on a number of particular translations. I especially targeted translations such as the TNIV and NLT which I thought had been unfairly attacked more than any other versions. On this blog I went on the offensive promoting these translations, and on the greater blogosphere, I went on the defensive defending them whenever I thought they were given unfair treatment. The good news is that I see fewer and fewer of these kinds of negative posts. When I first started looking for them, I saw multiple posts every week. Since they often made the same charges over and over again, I began compiling a file of my own arguments so that I wouldn't have to retype so much information every time. I can honestly say now that sometimes entire weeks go by, and I really don't find that much to address. It's certainly still out there, and I don't think a ceasefire has been called in the Bible wars, but maybe we've seen a lull in the fighting and things will continue to die down a bit.

It's really pointless in my opinion. I mean who would go into Baskin Robins and try to convince people only to get chocolate mint when there are 30 other flavors to choose from? However, most of the folks who do this kind of thing with Bibles honestly think they are correct in their arguments. They somehow think they are defending God's honor and God's Word. The nonsense about the TNIV removing the masculinity of the Bible is just that--nonsense. All modern translations have moved away in some degree from masculine universals. Even the ESV, the most conservative of the new translations, has made a number of changes in this regard from the RSV. In many instances "sons" has been changed to "children" and "a man" has been changed to "anyone." These changes are certainly legitimate, but I don't think it's fair to label the TNIV or the NLT as translations that remove masculinity when even the most conservative of the modern translations (and not just the ESV, but also the NASB95) have done the same thing to at least some extent.

Further, the most recent argument I hear being thrown around is that dynamic/functional equivalent translations violate the command in Rev 22:18-19 to not add to or take away. Such an assertion is problematic on multiple levels. First, the actual command really applies only to the original manuscripts (this is why I favor newer translations because they are based on the most up to date editions of our Greek and Hebrew texts that are the results of very strong convictions to represent the original words of the biblical writers as accurately as possible). But if someone is just counting by numbers, every translation adds or takes away words to communicate the message of the original. Further, to say that translations like the TNIV or NLT violate Rev 22:18-19 would also eliminate the first major translation of the Bible, the Septuagint. The Septuagint itself does not follow one strict model of translation, and the student of the LXX will discover that some portions are quite literal and others are quite dynamic, even paraphrased at times. Are we going to level restrictions that would even eliminate the translation that the apostles, New Testament writers, and Jesus himself used? I think not. Really, to make such a claim as this reveals little more than a lack of knowledge for translation and translation history, and it serves to simply scare the average church member and cause unnecessary mistrust of certain versions.

The Current State. There seems to be a Bible for everyone, doesn't there? In the end this should be something to celebrate because it allows God's Word to communicate to the largest number of people possible. But do we have too many? The claim is often made that English speakers have countless translations which come only at great effort and expense while there are still some language groups that do not have the Bible at all in their language. This may be true. Our culture seems to find a way to bring gluttony into everything, and so perhaps we do so as well with Bibles. But nevertheless they are here. We can't untranslate any of them. And the reality is, as demonstrated in the various categories of my Top Ten, most of them fulfill a particular kind of niche.

So are all the niches filled? The English language will continue to change and textual criticism will improve, so there will be a need for new translations in the future. But I cannot imagine the need for any new translations right now. Perhaps the Orthodox Study Bible (OSB) that I mentioned earlier this week is a legitimate exception. This will be the very first official translation of the Bible for English-speaking believers in the Orthodox Church, so that seems like a legitimate niche. But I really cannot imagine any other niche that needs to be filled. Anyone thinking of forming a new committee to create a brand NEW translation should really rethink that idea--in my opinion.

Speaking of niches and the OSB, I'm really surprised that we haven't seen more translations based on the above mentioned TR/MT texts that have been released in recent years. I find that holders to the Textus Receptus/Majority Text/Byzantine textform traditions to be very vocal about their convictions. But I'm surprised that I haven't seen more translations based on this. It is well known that the HCSB was originally based on Farstad & Hodges Majority Text edition back when Farstad was till alive (Lifeway, who bought the copyright moved it to the eclectic text after Farstad's death). The edition of the Majority Text released two decades ago by Farstad and Hodges seemed to be readily embraced by a number of adherents (or at least a very vocal number). But in my own collection of translations, I only count one Bible version based on it, and it was self-published by the translator--certainly not a significant project in the big scheme of things. The text edition in vogue right now for many of these folks seems to be Byzantine Textform produced in 2005 by Maurice Robinson and the late William Pierpont. Who knows if we will see a translation based on this edition sometime in the future, especially since Robinson commands a significant amount of influence at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary. Or maybe if the upcoming OSB isn't too sectarian, and if it could be released simply as a text edition, it might do it for these folks.

But one thing we definitely don't need is yet another modern language update to the King James Version. There are half a dozen or more of these already: some in print, some only available online. I'll say it again... I don't know why the NKJV isn't enough for these folks.

Regardless, your options are out there. No one has an excuse not to read the Bible because it's supposedly too hard to understand. Certainly, there are still concepts that require serious study, but from a contemporary language perspective, all bases seem to be covered right now.

Here on This Lamp we will continue to review Bible translations. If I've reviewed 10 I suppose I still have a few dozen more to go. I have a life goal to read through all these, too, but unless I receive a gift of longevity, I may not be able to accomplish that goal--especially at the rate they seem to be published.

My thanks goes to you readers who have interacted in the comments providing feedback and occasionally even offering a guest blog entry. Keep it coming; there's still lots to discuss.

Up next: Top Ten Bible Versions: The Complete Boxed Set

Top Ten Bible Versions: The Honorable Mentions

In hindsight, I don't know if the "Top Ten" designation was all that accurate because these aren't the ten Bibles I use the most. But in addition to the first few which I actually do use a good bit, I also wanted to introduce a few other translations that have stood out to me over the past couple of decades since I began collecting them. There are a few other Bibles that were contenders for such a list. I thought that I could briefly mention them in this follow up post.

King James Version.

I would imagine that if most people put together a top ten list, the KJV would be on it. I almost included it, but it seemed too predictable. Plus, I'm in no position to necessarily write anything new on the KJV (not that my other posts were wholly original either). Nevertheless, the KJV does deserve recognition because no other English translation has held the place of prominence that it has in the history of translations. It is still used today as a primary Bible by millions of Christians, still ranks somewhere in the top three positions of sales in CBA rankings, and even for those who have moved onto something newer, it is still the translation that verses have been memorized in like no other version.

I predict this is the last generation in which the KJV will still receive so much attention, but I have no trouble saying I may be wrong. It's difficult to say that one can be reasonably culturally literate--especially when it comes to the standards of American literature--without a familiarity of the KJV. Nevertheless, I cannot in good judgment recommend the KJV as a primary translation for study or proclamation because its use of language is too far removed from current usage. I don't mean that it's entirely unintelligible--not at all. But a primary Bible should communicate clear and understandable English in keeping with the spirit of the Koiné Greek that the New Testament was written in. I also cannot recommend it as a primary Bible because of the manuscript tradition upon which it rests. There's simply too much that has been added to the text. It was certainly the most accurate Bible in its day, but this is no longer true. My exception to this, however, is that I do find the KJV acceptable for public use with audiences made up primarily of senior citizens since this was exclusively their Bible. And the KJV still seems to be appropriate for use in formal ceremonies including churches and weddings--although I have not recently used it for such.

There is some confusion on what is actually the true King James version. Most do not realize that the average KJV picked up at the local book store is not the 1611 edition, but rather a 1769 fifth edition. And the reality is that there are numerous variations of this out there. For those who want a true and unadulterated KJV, the recently released New Cambridge Paragraph Edition seems to be the one worth getting.

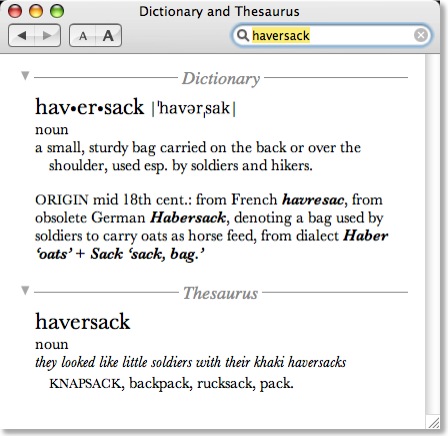

The NET Bible.

The NET Bible is one of about four translations (including the ESV, NRSV, and KJV) of which I received the most emails asking why it wasn't included in my top ten. The primary initial reason for the NET Bible's exclusion was simply that I had not spent enough time with it. I made the unfortunate decision to purchase a "2nd beta edition" only a few weeks before the final first edition came out (of which I recently obtained a copy).

Everyone I've heard speak about the NET Bible has high remarks about the 60K+ notes that come with the standard edition. And I can honestly say that these notes have become a regular resource for me when I study a passage. I don't hear as much high praise for the translation itself, though I don't hear anything particularly negative about it either. In general, though, I do recommend the NET Bible. I really like the editions I've seen made available--not just the standard edition, but also the reader's edition, and the Greek/English diglot which I'm very impressed with. The notes in the diglot are a slightly different set than what is in the standard edition. The "ministry first" copyright policy and the ability to download the NET Bible for free from the internet are very commendable on the part of its handlers.

I'd like to see the NET Bible get more attention, and I'd like to see more people introduced to it. I'm not sure it will get the widespread attention it deserves as long as it can only be obtained through Bible.org. In spite of the fact that my top ten series is over, I am going to continue to review translations, and the NET Bible will probably receive my attention next. But we have to spend some quality time together first.

The Cotton Patch Version.

I decided not to include a colloquial translation in my top ten, but if I had, the Cotton Patch Version of the New Testament would have held the category. Most colloquial translations are fun, but a bit gimmicky. The Cotton Patch Version rendered from the Greek by Clarence Jordan was anything but gimmicky. During the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960's, Jordan recast the events of the New Testament in the Southern United States. Replacing Jew and Gentile with "white" and "negro," and status quo Judaism with Southern Baptists (of which he was one), Jordan clearly brought the radical message of the New Testament into current contexts. The Cotton Patch Version is certainly fun reading if you are familiar with Bible Belt southern locales, but more importantly, the message is gripping as well.

The New Revised Standard Version.

The NRSV is an honorable mention I've added since I first announced the series. Originally, I felt like the NASB represented both the Tyndale tradition and formal equivalent translations well enough, plus at the time my use of the NRSV had become quite rare. Then my little NASB vs. NRSV comparison that I wrote with Larry revived my interest in the NRSV, and I now even have a copy sitting on my desk.

A year ago, I would have thought that the NRSV had seen its last day in the Bible version spotlight--except for academic use, but it seems to have had a bit of a renaissance with new attention and even new editions being published. It is still the translation of choice for the larger biblical academic community, primarily in my opinion because it has the widest selection of deutero-canonical books available of any translation. In its early days the NRSV was also embraced by many in the evangelical community but such enthusiasm seems to have waned. I think than rather than fears of theological bias, evangelical readers simply have too many other versions to choose from since the release of the NRSV.

Yes, the NRSV may be a few shades to the left of evangelical translations, but I've spent enough time with it to state clearly that it is not a liberal Bible. Don't let sponsorship from the National Counsel of Churches drive you away. If that were the only factor in its origin, I'd be skeptical, too, but the fact that Bruce Metzger was the editorial head of the translation committee gives me enough confidence to recommend it--if for nothing else, a translation to be read in parallel with others.

Well, is the series done? Not quite yet. I'll come back later this week with a few concluding thoughts about the list and the current state of Bible translations in general.

The Modern Language Bible: New Berkeley Version (Top Ten Bible Versions #10)

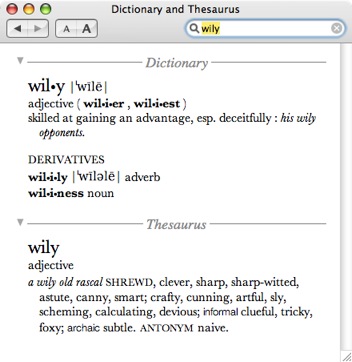

The serpent, wiliest of all the field animals the Lord God had made, said to the woman,

“So, God told you not to eat from any tree in the garden?”

(Gen 3:1, MLB, emphasis added)

Quite a few years before the NIV, Zondervan published a new translation of a New Testament called The Berkeley Version. It would later expanded to the entire Bible, and eventually receive a name change: The Modern Language Bible: The New Berkeley Version in Modern English.

However, even beyond a common publisher, there’s still another connection that the MLB has with the NIV. If history had turned out a bit differently, there’s a strong chance that the MLB--and not the NIV--could have risen to become the English-speaking world’s top-selling translation. Who knows? Perhaps instead of the TNIV, we’d have had Today’s Modern Language Bible (the TMLB!) for critics to be upset over.

Background. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Some may be wondering how the MLB came to be. This translation began as audacious dream of Gerrit Verkuyl, a Presbyterian minister and staff member of the Board of Christian Education of the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A. I say that the dream was audacious for two reasons. First, for Verkuyl, English was not a primary language. Nevertheless, this Dutch-born immigrant to the United States desired to create a Bible translation in modern English. Second, the seeds of this dream had been planted in Verkuyl's spirit during his undergraduate studies at Park College in Missouri where a professor instilled in him a love for Greek, and Verkuyl began comparing the Greek New Testament with the King James Version and the Dutch Bible he was most familiar with. Verkuyl determined that his Dutch Bible was more faithful to the Greek than the KJV, and he longed for a modern and accurate version to be made available in his newly adopted tongue, English. Yet, Verkuyl's career got in the way of his idea for a new translation, and work did not actually begin on it until he reached retirement at the age of 65! But if Moses' most important mission didn't begin until he was eighty, Verkuyl was not about to let his age get in the way of his dream.

In 1936 Gerrit Verkuyl began working on his modern language New Testament. A year later he moved to Berkeley, California, and in 1939 he retired from the Board of Christian Education so that he could devote his full energies to his translation. Borrowing the name of his new home, Verkuyl published the first edition of The Berkeley Version of the New Testament in 1945. The publishing rights were eventually transferred to Zondervan where there was interest in creating a complementary Old Testament as well. Such a large project as an Old Testament translation was outside the bounds of Verykuyl's abilities, especially at his advanced age. But a team of nineteen Hebrew scholars was put together who worked under Verkuyl's supervision to create a new translation of the Old Testament using the same principles and guidelines that Verkuyl had followed in translating his New Testament. The entire Bible was finally published in 1959 as The Berkeley Version of the Bible in Modern English. Verkuyl's lifelong dream which began when he was in his twenties, and was not commenced until he was in his sixties, was not fully completed until he was 86 years old!

The staff of Old Testament translators for the 1959 edition reads like a who's who of mid-twentieth century evangelical OT scholarship:

Gleason Archer, Fuller Theological Seminary

John W. Bailey, Berkeley Baptist Divinity School

David E. Culley, Western Theological Seminary

Derward W. Deere, Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary

Clyde T. Francisco, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

Leonard Greenway, Pastor, Bethel Christian Reformed Church

Howard A. Hanke, Asbury College

S. Lewis Johnson, Dallas Theological Seminary

James B. Keefer, Missionary, United Presbyterian Church

William Sanford LaSor, Fuller Theological Seminary

Jacob M. Myers, Lutheran Theological Seminary

J. Barton Payne, Trinity Theological Seminary/Wheaton College

George L. Robinson, McCormick Theological Seminary

Samuel Schultz, Wheaton College

B. Hathaway Struthers, chaplain, U. S. Navy

Merrill F. Unger, Dallas Theological Seminary

Gerard Van Groningen, Reformed Theological College

Gerrit Verkuyl, Presbyterian Board of Education

Leon J. Wood, Grand Rapids Theological Seminary and Bible Institute

Martin J. Wyngaarden, Calvin Theological Seminary

Of the 1959 edition, F. F. Bruce wrote, "The Berkeley Version is the most outstanding among recent translations of both Testaments sponsored by private groups." And although he continued his enthusiasm toward the translation, especially the Old Testament, Bruce went on to point out numerous errors and questionable renderings in in 1961 book, The History of the Bible in English. Although the MLB was generally well received, the criticisms by Bruce and others led to another revision by E. Schuyler English, Frank E. Gaebelein, and G. Henry Waterman. That edition--said to be a revision, not a re-translation in the preface--was published in 1969, after the Verkuyl's death. The 1969 edition also received a new name: The Modern Language Bible: The New Berkeley Version in Modern English. According to the book, House of Zondervan,

the old [name] had become the victim of current events. The university in the city for which the version was named--Berkeley, California--had become a center of student revolt and the Free Speech Movement in the mid to late sixties, and the name Berkeley was a byword for antiestablishment protests.

Of course, the MLB was an antiestablishment protest in a sense. It was a protest against the KJV as the primary Bible used by English speaking Christians of his day.

The NIV Connection. So what's the MLB's relationship to the NIV? Well recently, David Dewey (author of A User's Guide to Bible Translations) and I were discussing the MLB via email correspondence. Dewey reminded me that if history had turned out a little differently, there's a strong possibility that the NIV would have never been and it might have been the MLB that went on to become the English-speaking world's most popular Bible versions. David wrote:

Apparently, when the National Association of Evangelicals inquired into a translation suitable for evangelical and evangelistic purposes, various options were considered before a decision was made to go for an entirely new translation. The options included the NASB, an evangelical edition of the RSV (how ironic we now have the ESV!) and Verkuyl's work

From David Dewey's book, A User's Guide to Bible Translations, in regard to the NIV:

As early as 1953 two separate approaches to inquire if an evangelical edition of the RSV might be permitted were declined. (One was made by the Evangelical Theological Society, the other by Oaks Hills Christian Training School, Minnesota. See Thuesen: In Discordance with the Scriptures, page 134). Separately from this, in 1955, Christian businessman Howard Long asked the Christian Reformed Church, of which he was a member, to consider the need for a Bible suited to evangelistic work. In 1956 the Synod of the CRC appointed a committee to consider the possibility. Independently of this, the National Association of Evangelicals set up a similar inquiry in 1957. A joint committee of the two groups was formed in 1961.

In a two-hour meeting in 1966 with Luther Weigle, chairman of the RSV committee, the option of preparing an evangelical edition of the RSV was again refused, despite a Catholic edition appearing in the same year. Other translations, including the Berkeley Version and the as yet incomplete NASB were also deemed unsuitable for what was in mind. So work on the NIV began in 1967, undertaken by the New York Bible Society (subsequently renamed the International Bible Society and relocated to Colorado Springs).

But who knows? Consider that in his section on The Berkeley Version of 1959, F. F. Bruce wrote the following:

The general format of this version reminds one forcibly of the Revised Standard Version, and it might not be too wide of the mark to describe it as a more conservative counterpart to the RSV

But in reading the rest of Bruce's review, one might understand why the Berkeley Version was passed up in favor of a brand new translation that would become the NIV. In reality, as demonstrated by Bruce, the 1959 still had quite a few rough spots. And Bruce's treatment today is a bit frustrating because although his book was updated in both 1970 and 1978, in neither one does he update his review. The reality is that when one compares Bruce's criticisms of the New Berkeley Version to the 1969 revision reflected in the MLB, the vast majority of them were corrected! Obviously, the revisers took into consideration Bruce's critique clearing up almost 90% of his concerns (but oddly leaving a few glaring ones intact). In the 1978 edition of Bruce's book, he merely adds this disclaimer: "The Berkeley version was revised as The Modern Language Bible, and many of the above-mentioned "stylistic oddities" were happily replaced by acceptable renderings (1969)." In my opinion, a much better survey of the MLB is found in the now out-of-print So Many Versions? (1983 edition) by Sakae Kubo and Walter F. Specht. In fact, these authors devote an entire chapter consisting of nine pages to the MLB--the most complete treatment of this Bible version I've seen yet.

Character and Significance. Gerrit Verkuyl wrote of his Berkeley Version that

I aimed at a translation less interpretive than Moffatt’s, more cultured in language than Goodspeed’s, more American than Weymouth’s, and less like the King James Version than the RSV.

In large part, he succeeded at his goal. He saw a definite need for a Bible translation such as his in the era in which he lived. Admittedly if one were to pick up the MLB for the first time today, it might come across as totally unremarkable in terms of contemporary language. In fact, at this point, it might be a bit dated in places. But this was not so in Verkuyl's day when the vast majority of Christendom still used the King James Version. One cannot even truly grasp the significance of the MLB without realizing that it was primarily created to counter the KJV's dominance in the English-speaking Church. By contrast, we have so many "modern language" Bibles to choose from today, we easily forget that merely a generation ago this was not the case.

Perhaps the fact that English was not Verkuyl's original language allowed him to see the inherent problems with a four-century old translation more easily.

A little girl from a Christian home asked me, “Why do I have to suffer to come to Jesus?” (Matt. 19:14, AV). Upon my reply that Jesus loves children and makes those happy who come to Him, she quoted what she had learned in Sunday School, and what she understood Jesus had said, “Suffer, little children to come to me.” How utterly contrary to our Lord’s intention was this small child’s conclusion! Divine revelation is intended to reveal His thoughts, but to this child the words of the AV failed to convey our Lord’s gracious invitation and no amount of dignity or rhythm can make up for such a failure. That child is entitled to a language in which it thinks and lives, and this is a right all human beings deserve.

Some might wonder where the MLB stands on the scale of translation (literal/formal/median/dynamic/paraphrase). I've never seen this directly addressed in any analysis of the MLB. Nevertheless, in my evaluation, the MLB is still basically a formal equivalent translation, but perhaps not so much as the RSV of its day. I'd probably place it on the scale somewhere between the RSV and the NIV as it does not quite reach the freedom in rendering that the latter does. Nevertheless, Verkuyl does seem to talk of moving away from a strict world-for word method in order to reach the thoughts of God. In the preface to the original Berkeley New Testament, Verkuyl wrote

As thought and action belong together so do religion and life. the language, therefore, that must serve to bring us God's thoughts and ways toward us needs to be the language in which we think and live rather than that of our ancestors who expressed themselves differently.

Certainly this is true and a reality that translators should keep in mind today concerning common use translations.

In Matt 19:25, many translations render ἐκπλήσσω with the word amazed or slightly better astonished. But I've never thought that these words quite capture the meaning of the original. Yet, see how the MLB translates the verse:

When the disciples heard this, they were utterly dumbfounded, and said, "Who then can be saved?" (Matt 19:25)

Some will find the overt legal terminology questionable, but the MBL's rendering of παράκλητος certainly brings out that aspect:

Dear children, I write you these things so you may not sin, and if anyone does sin, we have a counsel for our defense in the Father's presence, Jesus Christ the Righteous One. (1 John 2:1)

While other translations were still translating ἱλασμός as propitiation or expiation, Verkuyl used something more simpler, perhaps even influencing later translations such as the NIV:

He is Himself an atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not for ours only, but also for the whole world. (1 John 2:2)

No "broken pieces" in Mark 8:8. Rather something that is immediately understandable:

So they ate and were satisfied; and they picked up the leftovers, seven baskets full. (Mark 8:8)

The camaraderie that was surely present between Jesus and the disciples is reflected in a verse like this:

Then Jesus said to them, "Boys, have you caught anything?" They answered Him, "No." (John 21:5)

But perhaps at times, the rendering is a bit too modern:

Another unique rendering that demonstrates Verkuyl's sensitivity to the original languages is found in his translation of μέγας in Matt 18:4. I'm not sure what lexicons Verkuyl consulted for his work, but obviously it was not the newest edition of the BDAG. Nevertheless, in my copy (which is the 2000 third edition), μέγας in Matt 4:18 is listed with the meaning "pertaining to be relatively superior in intensity, great." The problem is that this relative aspect is somewhat lost when most translations simply use the word, greatest. Note how the MLB renders the verse remaining true to the relative use of μέγας in this verse:The disciple whom Jesus loved then said to Peter, "It is the Lord!" So Simon Peter, hearing "It is the Lord," wrapped his work jacket around him (for he was stripped) and flung himself into the sea. (John 21:7)

Whoever then humbles himself like this little child, he excels in the kingdom of heaven. (Matt 18:4)

Although the MLB was in many ways a reaction against the dominance of the KJV, and although Verkuyl did not tie himself to Tyndale-tradition renderings, nevertheless, he was still sensitive to the fact that most of his readers would still be very well acquainted with the KJV. According to Kubo and Specht, Verkuyl based the original Berkeley NT on the 8th edition of Tichendorf's Greek text in consultation with the Nestle text of his day. Knowing that his translation would be read by those more familiar with the KJV, he often included Textus Receptus readings in brackets within the text. So with the Lord's Prayer in Matthew six, Verkuyl adds the phrase "For Thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever. Amen," but does so bracketed. He included such phrases in the actual text because he knew that these were readings that would be made in the church. The MLB was not merely meant to be read alongside the KJV, but to supplant it for as many people willing to do so. In explanation to the verse mentioned above, a footnote appears:

The words enclosed in brackets are not found in the majority of the most reliable ancient manuscripts. They have been added to the text here to make the prayer more appropriate for public worship. Certainly the last sentence is compatible with Scripture. Cf I Chron. 29:11. In Luke's account of the Lord's Prayer, Lk. 11:2-4, this sentence is omitted.

One very nice feature of the MLB is the abundance of footnotes to the text. Verkuyl believed that footnotes to the text could and should be used as frequently as necessary to help the reader bridge that gap between the languages and contexts of the original authors. Some footnotes are textual in nature such as the one quoted above. But many have to do with backgrounds/historical issues or even explanations of Greek or Hebrew words. A few tend to be more applicatory. On the same page as as the footnote quoted above, one finds these explanations:

- For robe and tunic in Matt 5:40-- "A tunic reached to the knees; a robe was a long outside garment which reached almost to the ankles."

- For Matt 5:43, cross-references are offered: "Lev. 19:18; Deut 23:3-6."

- A note of application is given for Matt 5:45-- "We show that we are God's sons by living His principles."

- For Matt 5:48, the word perfect is explained: "'Perfect' is from the Greek teleios meaning complete, mature."

- For 6:12, an interpretive explanation: "Debts [the word Verkuyl uses here in his translation], or trespasses in the sense of falling short of God's requirements."

Another modern aspect of the MLB was the desire by Verkuyl and the OT translators to give strictly modern equivalents to weights, measures and even currency. Consider these verses from the MLB compared with the most recent of the contemporary translations, the TNIV:

GENESIS 6:15 |

|

MLB |

TNIV |

| Construct it after this fashion: The length of the ark 450 feet; its width 75 feet and its depth 45 feet. | This is how you are to build it: The ark is to be three hundred cubits long, fifty cubits wide and thirty cubits high.* *That is, about 450 feet long, 75 feet wide and 45 feet high or about 135 meters long, 22.5 meters wide and 13.5 meters high. |

|

EXODUS 29:40 |

|

MLB |

TNIV |

| With the first lamb you shall offer an ample six pints of fine flour mixed with 3 pints of pressed olive oil; and a libation of 3 pints of wine. | With the first lamb offer a tenth of an ephah* of the finest flour mixed with a quarter of a hin** of oil from pressed olives, and a quarter of a hin of wine as a drink offering. *That is, probably about 3 1/2 pounds or about 1 1/2 kilograms |

EXODUS 38:26 |

|

MLB |

TNIV |

was about 12,000 pounds* around 65 cents per man for everyone registered from 20 years up, 603,550** men. *$201,000. |

one beka per person, that is, half a shekel,* according to the sanctuary shekel, from everyone who had crossed over to those counted, twenty years old or more, a total of 603,550 men. *That is, about 1/5 ounce or about 5.7 grams. |

|

MATTHEW 25:15 |

|

MLB |

TNIV |

To one he gave ten thousand dollars;* to another, four thousand; and to a third, two thousand--each according to his own ability; then he went away. *In vss. 15-28 the direct translation from the Greek text reads "five talents [pente talanta]," "two talents" and "one talent," and in vs. 29 "ten talents." A silver talent wouldbe equivalent to about $2000 in mid-twentieth century U.S. currency, so that the figures given in this edition are approximately accurate. |

To one he gave five bags of gold, to another two bags, and to another one bag, each according to his ability. Then he went on his journey. *Greek five talents . . . two talents . . . one talent; also throughout this parable; a talent was worth about 20 years of a day laborer’s wage. |

The desire to make measures and weights into modern equivalents is admirable. In recent translations, the NLT is probably best at this. Note that in Gen 6:16 quoted above, the original NIV had feet instead of cubits, but this was changed in the TNIV--further evidence of my contention that overall the TNIV is more literal than the NIV. Nevertheless, while an admirable goal for the MLB, surely the greatest challenge would have to do with currency. The TNIV demonstrates contemporary wrestling with this issue in the questionable use of "bags of gold" in Matt 25 (obviously this was done because the average reader confuses monetary talents with "special ability" talents). The MLB's use of "cents" in the OT somehow seems out of place. But the greater problem lies in rising inflation rates. Maybe inflation was not a great issue in the fifties and sixties, but such use today would quickly date a translation. At our current rate of language change, English translations of the Bible only seem to have about a 20 to 25 year life span in my estimation. But adding in current monetary values--especially oddly placed United States monetary values--would date a translation very quickly. Perhaps only the NET Bible with its promised five years for a fixed translation between editions could pull this off, but because of the other factors mentioned here, I would certainly not recommend it.

Like many translations of its day, the MLB uses more formal pronouns (thee, thy, thou) for addressing God in the Old Testament. In earlier editions this practice was continued in the New Testament as well referring to Christ, but only in certain contexts. In the 1969 revision, this practice was removed altogether from the NT, but retained in the OT. The MLB also used capital letters for pronouns referring to deity throughout both testaments. However, like the RSV, the MLB did not follow the KJV's practice of formatting words added for understanding in italics.

A rather odd feature of the original Berkeley Version was the non-use of quotation marks for any words spoken by God or Jesus. The rationale was that all of the Bible is God's Word and Jesus is the Word of God, so why use quotation marks? This practice was done away with in the NT for the 1969 revision, but retained in the OT which received less attention from the revisers. In spite of F. F. Bruce's enthusiasm for the MLB OT in the 1959 edition, I would suggest that in the final product of the 1969 edition, the NT is much more consistent and polished.

The MLB Old Testament is significant because it was one of the first English translations to take advantage of the newly discovered Dead Sea Scrolls. This version used the DSS to "fix" known problems in the Masoretic text. Nearly all modern translations do the same, today. But if I may be so bold as to disagree with "the Bruce," the MLB OT needed at least one more revisers' pass to make it thoroughly ready for widespread use. Part of the problem stemmed from a lack of editorial committees, a practice common in translations today. The OT scholars responsible for translating the OT were primarily left to themselves, having been given the instruction to follow the same "modern language" principles utilized by Verkuyl in his original NT. Then Verkuyl himself acted as a final editor for the OT, a very large task for one man, and one who was aging at that.

The most glaring inconsistency has to do with the use of the divine name, the Tetragrammaton. The MLB generally follows the principle used in most English translations by simply using the word LORD, spelled in all caps to represent God's name. However, like some modern translations, including the HCSB, there are some texts when reference is made to the name that the actual name itself would make more sense. But this name has been spelled differently over the centuries, and oddly enough, two different spellings show up in the MLB:

"Jehovah"

God said further to Moses, You tell the Israelites: Jehovah, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, of Isaac and of Jacob has sent me to you. This is My name forever and by this I am to be remembered through all generations. (Ex 3:15)

O Jehovah, our LORD, how glorious is Thy name in all the earth! (Psalm 8:1/9)

"Yahweh"

the LORD, the God of hosts, YAHWEH His name. (Hos 12:5)

And then one text where the reader might expect to see the name spelled out, it is not:

Seek Him who makes the Pleiades and Orion, who turns blackness to morning and darkens day to night; Him who calls the waters of the sea and pours them out on the face of the earth--the LORD is His name. (Amos 5:8)

Well, this is sloppy for more than just the inconsistency regarding the divine name. There are other problems in these texts. In Psalm 8:1/9 above, if Jehovah is used, LORD should not be in all caps because the second occurrence is adonai, not YHWH. And Hos 12:5 above is not a typo on my part. The text would read better with a verb added: "YAHWEH is His name."

One doesn't really wonder why the 1959 edition was passed over as a suitable translation to be used in evangelical and evangelistic purposes. The translation, especially the OT, was still a bit rough. But these very errors mentioned immediately above were noted by F. F. Bruce, so it's surprising they weren't corrected in the 1969 revision because other issues certainly were changed. Nevertheless, the MLB retains a significant place in 20th century translations, but was eclipsed by later translations, especially the NIV.

What's Available and Concluding Thoughts.I picked up my first copy of the MLB sometime in the late eighties--a green paperback Zondervan edition with California grapes on the cover. Technically, this translation was past its prime by the time I came to the party, but for whatever reason I clicked with it. Many nights at church, since I wasn't teaching, I left my NASB at home and carried my MLB. In fact, in many ways, in those pre-computer days, it was one of my most used secondary Bibles.

When I first put together this list of top ten Bibles, I tried to make clear that although some of them really were translations I used a good bit, others were not--but were primarily "best of" a certain category of Bible. To me, the MLB--specifically the NT--stands as one of the best (and most consistent) single-translator Bible versions ever produced in the 20th century. These days, committees produce most of our English translations. But we should be careful to remember that individuals have been responsible for quite a few translations that are worthy of our attention. This includes Bible versions such as those produced by Tyndale, Moffatt, Goodspeed, Beck, Phillips, Taylor, certainly Verkuyl, and a host of others.

To be honest, I don't use the MLB all that much anymore. Frankly, I'd use it more if I had an electronic edition in Accordance, but I can't find electronic editions anywhere except one made for PDA's. That means it is available in an electronic edition, just not a practical one (for my purposes). However, to its credit, the MLB has not yet gone out of print in its 60 years of publication. In 1990, after a near-exclusive history with Zondervan, the rights were transferred to Hendirickson Publishers. When Hendrickson took over, they released a nice hardback edition which I promptly bought and gave away my green Zondervan paperback to a minister friend. Currently, that hardback edition is no longer in print, but Hendrickson does make available a copy of the MLB in paperback (ISBN 1565639316). If you consider yourself an enthusiast of Bible translations, your collection is nowhere near complete without the MLB.

Whether or not the MLB (or the earlier Berkeley Version) was ever published in leather, I have no idea. Every copy I've ever seen, even of the original editions were hardback. If someone knows differently, let us know in the comments.

The MLB is definitely past its prime. I don't see the MLB getting any attention on the copyright pages of Christian books anymore. But it certainly did for a while. It was widely used in evangelical publishing--usually as a secondary translation, but there were also a handful of books based primarily on it. Billy Graham even gave away copies of the NT at his crusades, I've been told as recently as the early nineties. Certainly more than a footnote in Bible history, the MLB at least was an important chapter as English-speaking Christians gradually began to move away from the KJV. If the MLB was a "conservative RSV," it was eventually replaced by others translations which were even more so, including the NASB and the NIV which ultimately eclipsed it. But it almost was the NIV. Would history have turned out differently if the equivalent of the 1969 edition had already been released when the search was on for a modern English translation to use for evangelistic purposes?

The MLB seems to be a translation that could have been much more. In truth, it needed one more revision that never came. Within less than ten years of its final edition, its publisher Zondervan began marketing the first edition of a new translation, the New International Version--which finally did unseat the KJV as the most used English translation. While the NIV really was a better translation overall, the MLB had a bit of personality that I'm not sure was present in the NIV. I mean, you don't see clever renderings like wiliest in Gen 3:15 in the NIV (although check out NIV Job 5:18). There may be a word of warning here, too. Even a good translation can fall into disuse if neglected in favor of another by a publisher simply because one will bring in more money. I would like to continue to encourage Zondervan to transition itself away from the NIV as a base translation to its successor the TNIV, something that has been slow to take place. I'd hate to see the TNIV sitting beside the MLB one day as another victim of the NIV's success.

Sources used:

F. F. Bruce, The History of the Bible in English

David Dewey, A User's Guide to Bible Translations

Sakae Kubo and Walter F. Specht, So Many Versions? 20th Century English Versions of the Bible (out of print, but used copies are still available)

James E. Ruark, The House of Zondervan

Gerrit Verkuyl, "The Berkeley Version of the New Testament" (this article was written before the final editions, so some references have been changed, but it provides a good introduction and insight into Verkuyl's vision and goals).

Up Next: The Honorable Mentions: The KJV, the NET Bible, the Cotton Patch Version...and one more that I've added since I made the original list...

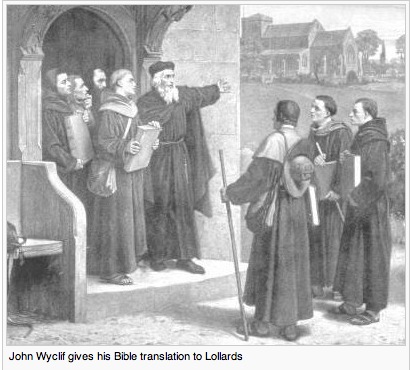

The Wycliffe New Testament [1388] (Top Ten Bible Versions #9)

And shepherds were in the same country, waking and keeping the watches of the night on their flock. And lo, the angel of the Lord stood beside them, and the clearness of God shined about them, and they dreaded with a great dread. And the angel said to them, Nil ye dread, for lo, I preach to you a great joy that shall be to all people. For a Saviour is born today to you that is Christ the Lord in the city of David. And this is a token to you, ye shall find a young child lapped in cloths and laid in a creche. And suddenly there was made with the angel a multitude of heavenly knighthood, herying God and saying, Glory be in the highest things to God, and in earth peace to men of good will.

From the Gospel of Luke, chapter II

I've said before that my "Top Ten" list of Bibles is somewhat categorical in nature. One of the categories that I wanted to see represented in this series when first thinking about it was translation of a historical nature, a non-contemporary translation. I could have easily and logically picked the KJV, but it is so familiar, I doubt I could have added anything to the conversation. I came close to selecting the Geneva Bible or William Tyndale's translation, but I remembered that the era surrounding John Wycliffe had always captured my imagination.

I first discovered John Wycliffe (1320-1384) and his Lollard followers in college when I took a class devoted to Chaucer's writings. I felt immediate theological attraction to this individual often called "the morning star of the Reformation" and his conviction that all believers have a copy of the scriptures in their own native language. Later in seminary, while taking a church history class, I focused my attention on Wycliffe again as the subject of my term paper for that semester.

Then a couple of years ago, I was sitting in a seminar and I noticed one of the church history majors was reading from a very interesting Bible. Always interested in what version of the Scriptures people are reading, I looked closer to see The Wycliffe New Testament 1388 on the spine. Very much intrigued by this point, I asked him if I could look at it. He cautioned, "Yeah, but you should know that it's in Old English." Remembering my Chaucer class from years before, in which we were only allowed to read the texts in their original form in class (no modern translations or paraphrases allowed), I did my best not to sound too much like a know-it-all as I said, "Technically, that would be written in Middle-English." He looked at me with a blank stare and then said, "No, I think this is Old English." I saw him a few weeks later, and he said, "Hey, you were right--the Wycliffe Bible is written in Middle-English."

Thanks. It's probably a good thing that I didn't bring up the fact that it's very doubtful that Wycliffe had much direct influence on the translation that bears his name. Rather, most agree that the Wycliffe Bible (there were actually two different versions by that name) was produced by the Lollard community which was heavily influenced by John Wycliffe's teachings. The translation itself, while not the very first translation of the Scriptures into English, were the first product of Wycliffe's conviction that all believers, regardless of education or status had the right to access the Scriptures in their own language. The basis of the Wycliffe New Testament was the Latin Vulgate, which was ironically itself once a translation with the same goal but became a Bible for the privileged as fewer people spoke Latin.

Original copies of the Wycliffe NT were written and copied by hand. Since ownership of these texts was illegal, having a copy was a great risk. They were also very valuable, often with wheelbarrows of hay being traded for a few pages from the "pistle" of James or some other NT book. According to the introduction found in the printed copy I own, these handwritten pages of Scripture were highly treasured even long after the age of the printing press and the explosion of English translations in the sixteenth century. They only fell out of use after dramatic shifts in the English language.

The Wycliffe NT is somewhat unique because it contains the epistle to the Laodiceans, which is evidently in the Vulgate, but is no longer extant in the Greek. Although the Lollards recognized that the Catholic Church did not consider this book to be canon, they nevertheless did, assuming that it was the letter referred to in Col 4:16.

I picked up the same edition of the Wycliffe NT that the student mentioned above had. It's a very solid hand-sized hardback binding with a nice blue ribbon, published by the The British Library in association with the Tyndale Society. The pages are made from "normal" paper as opposed to Bible thin paper, and I would guess that they may be acid free. This New Testament uses a stitched binding so no doubt, it will hold together for quite a long time. If one might be prone to take notes, there are ample one inch margins interrupted only occasionally with a definition of an overly-archaic word in the text. Spelling has been modernized, and (unfortunately, in my opinion) so have many of the words. This is not really a difficult read--nothing like my Chaucer class--but it will slow down the average reader (which is often a good thing). Why some archaic words were updated and others were left alone, I have no idea. Like the original Wycliffe NT, this edition does not have verse divisions, but does contain chapter numbers.

The order of books is different from our Bibles with Acts (or "Deeds" in this version) coming after Paul's "pistles" which not only include the aforementioned letter to the Laodiceans, but also includes the letter to the Hebrews, assumed by most in the Middle Ages to have been written by Paul. For some odd reason, there's no table of contents which would have been very helpful because of the non-standard arrangement of books.

Some passages of interest:

And Jesus, seeing the people, went up into an high hill, and when He was sat, His disciples came to Him. And He opened His mouth and taught them, and said, Blessed are poor men in spirit, for the kingdom of heavens is theirs. Blessed are mild men, for they shall wield the earth. Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted. Blessed are they that hunger and thirst rightwiseness. for they shall be fulfilled. Blessed are merciful men, for they shall get mercy. Blessed are peaceable men, for they shall be called God's children. Blessed are they that suffer persecution for rightfulness, for the kingdom of heavens is theirs.

...

Ye have heard that it was said to old men, Thous shall do no lechery. But I say to you that every man that sees a woman for to covet her, has now done lechery by her in his heart. That if thy right eye sclaunder thee, pull him out and cast from thee, for it speeds to thee that one of thy members perish than that all thy body go into hell. And if thy right hand sclaunder thee, cut him away and cast from thee, for it speeds to thee that one of thy members perish than that all the body goe into hell. And it has been said, Whoever leaves his wife, give he to her a libel of forsaking. But I say to you that every man that leaves his wife, out-taken cause of fornication, makes her to do lechery. And he that weds the forsaken wife, does advowtry.

from the Book of Matthew, chapter V

And I comment to you Phoebe, our sister, which is in the service of the church at Cenchrea, that ye receive her in the Lord worthily to the saints, and that ye help her in whatever cause she shall need of you

....

Greet well Andronicus and Junia, my cousins and mine even prisoners, which are noble among the apostle and which were before me in Christ.

from the pistle of Paul to the Romans, chapter XVI

Paul, apostle, not of men nor by man, but by Jesius Christ, to the brethren that are at Laodicea, grace to you and peace, of God the Father and of the Lord Jesus Christ. I do thankings to my God by all my prayer that ye are dwelling and lasting in Him, abiding the behest in the day of doom. For neither the fain speaking of some unwise men has letted you, the which would turn you from the truth of the gospel that is preached of me. And now them that are of me to the profit of truth of the gospel, God shall make deserving and doing benignity of works and health of everlasting life. And now my bonds are open which I suffer in Christ Jesus, in which I glad and joy. And that is to me to everlasting health that this same thing be done by your prayers and ministering of the Holy Ghost, either by life, either by death. Forsooth, to me it is life to live in Christ, and to die joy. And His mercy shall do in you the same thing, that you moun have the same love and that ye are of one will. Therefore, ye well beloved brethren, hold ye and do ye in the dread of God, as ye heard [in] the presence of me, and life shall be to you without end. Soothly, it is God that works in you. And, my well beloved brethren, do ye without any withdrawing whatever things ye do. Joy ye in Christ, and eschew ye men defouled in lucre, either foul winning. Be all your askings open anents God, and be ye steadfast in the wit of Christ. And do ye those things that are holy and true, and chaste and just, and able to be loved. And keep ye in heart those things ye have heard and taken, and peace shall be to you. All holy men greet you well. The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be weith your spirit, and do ye that pistle of Colossians to be read to you

The Pistle to Laodiceans [in its entirety]

But Saul, yet a blower of menaces and of beatings against the disciples of the Lord, came to the prince of priests and asked of him letters into Damascus, to the synagogues, that if he found any men and women of this life, he should lead them bound to Jerusalem. And when he made his journey, it befell that he came nigh to Damascus. And suddenly, a light from heaven shone about him. And he fell to the earth, and heard a voice saying to him Saul, Saul, what pursues thou Me? And he said, Who art Thou, Lord? And He said, I am Jesus of Nazareth whom thou pursues. It is hard to thee to kick against the prick. And he trembled and wondered, and said, Lord, what will Thou that I do? And the Lord said to him, Rise up, and enter into the city, and it shall be said to thee what it behoves thee to do.

from the Deeds of the Apostles, chapter IX

My little sons, I write to you these things that ye sin not. But if any man sins, we have an Advocate anents the Father, Jesus Christ, and He is the forgiveness for our sins. And not only for our sins, but also for the sins of all the world. And in this thing we wit that we know Him, if we keep His commandments. He that says that he knows God and keeps not His commandments, is a liar, and truth is not in Him. But the charity of God is parfit verily in him that keeps His word. In this thing we wit that we are in Him, if we are parfit in Him. He that says that he dwells in Him, he owes for to walk as He walked.

from the first epistle of John, chapter II

And they had on them a king, the angel of deepness, to whom the name by Hebrew is Abaddon,, but by Greek, Apollyon. And by Latin he has the name Exterminians, that is, a destroyer. One woe is passed, and lo, yet come two woes.

from the Apocalypse, chapter IX

In case anyone misunderstands, I'm certainly not recommending the Wycliffe NT (or any other historical translation) as a primary study Bible. But there is great value in having older translations around for comparison and understanding the development of our English translations. Further, a historical translation can connect the reader to the generations who used it hundreds of years ago. Finally, there is great spiritual benefit when reading something like the Wycliffe NT for devotional purposes. I challenge you to give it a try, and don't be surprised if God speaks to you--even from the Middle English!

Next in series (and coming soon): The Modern Language Bible (New Berkeley Version)

The Good News Translation: Top Ten Bible Versions #8

“In the beginning, when God created the universe,

the earth was formless and desolate.

The raging ocean that covered everything was engulfed in total darkness,

and the Spirit of God was moving over the water.”

(Gen 1:1-2 GNT)

Thus begins the Good News Translation. The well-read Bible reader immediately notes the change in Gen 1:1 which in standard translations reads, "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth...." The GNT's use of universe accurately communicates the all encompassing Hebrew idiom, "heavens and earth, and for many readers, this simple rendering allows better understanding of the writer's point that everything that exists was created by God.

When I first compiled my list of top ten favorite translations for this blog, I wanted to include an entry for a common language translation. Part of my selection of the GNT is sentimental, but I hope that I can demonstrate the value of this translation as well.

What's in a Name?

First things first: what exactly is this translation called? The Good News Bible? Good News for Modern Man? Today's English Version? The Good News Translation? Throughout it's history, it's been called all of the above, and frankly it's confusing. In the blog entries where I've mentioned this version, I've probably used every one of those terms at some point.

Well, see if you can follow this. When the New Testament was first released in 1966, it was referred to as The Good News for Modern Man in Today's English Version. Then a decade later when the entire Bible was completed, it became the The Good News Bible in Today's English Version. It was revised in 1992, but the title didn't change. In fact, I didn't even know there had been a revision until last year and I collect translations of the Bible! In 2001 the name was changed again when Zondervan obtained North American publishing rights and asked that the designation be changed to Good News Translation since many perceived the GNT to be a paraphrase and not an actual translation (which it is).

An ironic aside: one of the main features of the 1992 revision was the further use of inclusive language for human references when the context warranted it. After Zondervan obtained publishing rights, one of the titles they resurrected (no doubt for familiarity's sake) was the classic title Good News for Modern Man, although that title is decidedly not inclusive. ![]()

Nevertheless, in spite of all the titles, it does seem a bit confusing. Interestingly, my copy of the text in Accordance is labeled "Today's English Version" and abbreviated "TEV" even though it has the 1992 copyright date of the 2nd edition. And when I ordered my copy of the 1992 revision directly from the American Bible Society (the owner of the translation), I noticed that my copy has both "Good News Bible" and "Good News Translation" on both the cover and the spine! Even more confusing, in looking at the most recent online catalog on the ABS website, I observed that there are pictures of the Bible that have both "Good News Bible" AND Today's English Version on them.

In keeping with most recent nomenclature, I will refer to this Bible version as the Good News Translation (or GNT for short) even when referring to the older editions.

What Kind of Bible Is This Anyway?

Back in the summer I came across a blog entry written by a youth leader who had tried to convince one of the young ladies at his church to get a different Bible than the GNT she was reading and for which she had a strong preference. Although in hindsight he regretted this discussion with her, he went on today how much he hated (he literally used that word) the GNT. When I tried to engage him in the comments about his opinion (and I tried my best to do so in a friendly way), he responded back that he was not even going to address my question, but concluded that "from a scholarly perspective, I believe I am on solid ground in saying that the Good News Bible is drivel."

Well, such a response is regrettable and I chose to pursue the discussion no further. But it does reveal ignorance about the GNT, its history, method of translation, and intended purpose.

The GNT started out as a project of the American Bible Society to create a New Testament specifically aimed at readers for whom English was a second language. Very quickly, however, they realized that there was an even broader audience. From the preface to the current edition of the GNT:

In September 1966 the American Bible Society published The New Testament in Today's English Version, the first publication of a new Bible translation intended for people everywhere for whom English is either their mother tongue or an acquired language. Shortly thereafter the United Bible Societies (UBS) requested the American Bible Society (ABS) to undertake on its behalf a translation of the Old Testament following the same principles. Accordingly the American Bible Society appointed a group of translators to prepare the translation. In 1971 this group added a British consultant recommended by the British and Foreign Bible Society. The translation of the Old Testament, which was completed in 1976, was joined to the fourth edition New Testament, thus completing the first edition of the Good News Bible Translation. Through previously known as Today's English Version (TEV) and commonly known as the Good News Bible (GNB), the translation is now called the Good News Translation (GNT).

The GNT was one of the first major Bible versions to apply the translational principles of dynamic equivalence as developed by Eugene A. Nida. A year after the release of the full edition of the Good News Bible, Nida himself wrote a wonderful little book that serves as an introduction to the translation, Good News for Everyone: How to Use the Good News Bible. Although out of print, the book is still obtainable through used book sources. The value in this volume lies not only in its introduction to the GNT, but also as an explanation and defense of dynamic equivalency from the leading developer and proponent of the method himself. On the principle of dynamic equivalency, Nida writes on p. 13,

The principle of dynamic equivalence implies that the quality of a translation is in proportion to the reader's unawareness that he is reading a translation at all. This principle means, furthermore, that the translation should stimulate in the new reader essentially the same reaction to the text as the original author wished to produce in his first and immediate readers. The application of this principle of dynamic equivalence leads to far greater faithfulness in translating, since accuracy in translation cannot be reckoned merely in terms of corresponding words but on the basis of what the new readers actually understand. Many traditional expressions in English translations of the Scriptures are either meaningless or misleading. How many present-day readers would know, for example, that "children of the bridechamber" (Matt. 9:15) really means "the guests at the wedding party" or that "bowels of mercies" (Col. 3:12) is better rendered as "compassion"?

The GNT is also in a category of translations known as a "common language Bible." In regard to this, Nida writes, "...the translation is produced in what is known as 'the common language.' This is the kind of language common to both the professor and the janitor, the business executive and the gardener, the socialite and the waiter. It may also be described as the 'the overlap language' because it is that level of language which constitutes the overlapping of the literary level and the ordinary, day-to-day usage" (p. 11-12).

The GNT is usually rated at about a 5th or 6th grade reading level, which puts it in the same market as similar translations that purposefully avoid larger vocabulary or technical language when possible such as the CEV, NCV, and NIrV. If an in-depth comparison of these specific translations exists I'm not familiar with it, but such analysis would certain be interesting.

To get a feel for the dynamic equivalency of the GNT compared a very literal translation such as the NASB, consider the following passages:

| Proverbs 1:8-9 | |

|---|---|

GNT |

NASB |

| 8 My child, pay attention to what your father and mother tell you. 9 Their teaching will improve your character as a handsome turban or a necklace improves your appearance. 10 My child, when sinners tempt you, don’t give in. 11 Suppose they say, “Come on; let’s find someone to kill! Let’s attack some innocent people for the fun of it! 12 They may be alive and well when we find them, but theyll be dead when were through with them! 13 We’ll find all kinds of riches and fill our houses with loot! 14 Come and join us, and we’ll all share what we steal.” 15 My child, don’t go with people like that. Stay away from them. 16 They can’t wait to do something bad. Theyre always ready to kill. 17 It does no good to spread a net when the bird you want to catch is watching, 18 but people like that are setting a trap for themselves, a trap in which they will die. 19 Robbery always claims the life of the robber—this is what happens to anyone who lives by violence. |

8 Hear, my son, your father’s instruction And do not forsake your mother’s teaching; 9 Indeed, they are a graceful wreath to your head And ornaments about your neck. 10 My son, if sinners entice you, Do not consent. 11 If they say, “Come with us, Let us lie in wait for blood, Let us ambush the innocent without cause; 12 Let us swallow them alive like Sheol, Even whole, as those who go down to the pit; 13 We will find all kinds of precious wealth, We will fill our houses with spoil; 14 Throw in your lot with us, We shall all have one purse,” 15 My son, do not walk in the way with them. Keep your feet from their path, 16 For their feet run to evil And they hasten to shed blood. 17 Indeed, it is useless to spread the baited net In the sight of any bird; 18 But they lie in wait for their own blood; They ambush their own lives. 19 So are the ways of everyone who gains by violence; It takes away the life of its possessors. |

Matthew 6:1-8 |

|

GNT |

NASB |

| 1 “Make certain you do not perform your religious duties in public so that people will see what you do. If you do these things publicly, you will not have any reward from your Father in heaven. 2 “So when you give something to a needy person, do not make a big show of it, as the hypocrites do in the houses of worship and on the streets. They do it so that people will praise them. I assure you, they have already been paid in full. 3 But when you help a needy person, do it in such a way that even your closest friend will not know about it. 4 Then it will be a private matter. And your Father, who sees what you do in private, will reward you. 5 “When you pray, do not be like the hypocrites! They love to stand up and pray in the houses of worship and on the street corners, so that everyone will see them. I assure you, they have already been paid in full. 6 But when you pray, go to your room, close the door, and pray to your Father, who is unseen. And your Father, who sees what you do in private, will reward you. 7 “When you pray, do not use a lot of meaningless words, as the pagans do, who think that their gods will hear them because their prayers are long. 8 Do not be like them. Your Father already knows what you need before you ask him. | 1 “Beware of practicing your righteousness before men to be noticed by them; otherwise you have no reward with your Father who is in heaven. 2 “So when you give to the poor, do not sound a trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, so that they may be honored by men. Truly I say to you, they have their reward in full. 3 “But when you give to the poor, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, 4 so that your giving will be in secret; and your Father who sees what is done in secret will reward you. 5 “When you pray, you are not to be like the hypocrites; for they love to stand and pray in the synagogues and on the street corners so that they may be seen by men. Truly I say to you, they have their reward in full. 6 “But you, when you pray, go into your inner room, close your door and pray to your Father who is in secret, and your Father who sees what is done in secret will reward you. 7 “And when you are praying, do not use meaningless repetition as the Gentiles do, for they suppose that they will be heard for their many words. 8 “So do not be like them; for your Father knows what you need before you ask Him. |

Rom 7:15-25 |

|

GNT |

NASB |