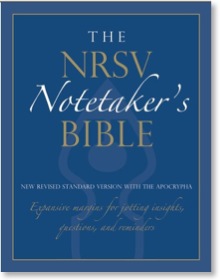

NRSV Notetaker's Bible

Product Description

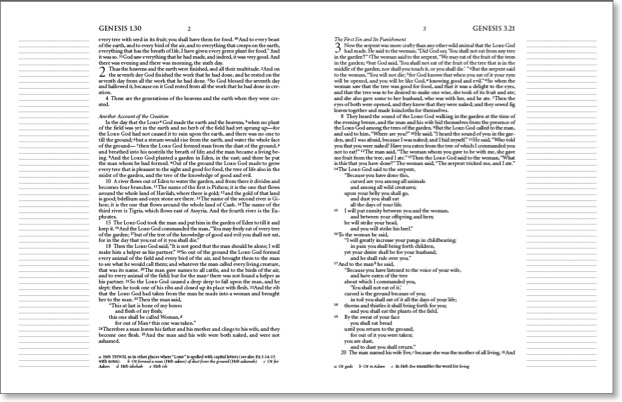

Perhaps you're one of those studious, deliberate readers who likes to underline phrases, create outlines, list cross-references, etc. Now you don't have to resort to cramped lettering or words in the gutter. This single-column text, with 2-inch wide-ruled margins, allows you ample room for making all manner of notes. 1632 pages, hardcover. Oxford University.

Publisher's Description

The Notetaker's Bible offers the perfect format for students of the Bible who wish to make their own notes--whether scholarly notations or spiritual insights--rather than rely on the words of others.

Some wide-margin Bibles have only slightly larger margins on both sides of the page. And writing in the gutter is nearly impossible. In The NRSV Notetaker's Bible, we've eliminated those frustrations by giving you an extra-wide, two-inch outside margin. And because the text is a single column, your notes are always right beside the relevant passage. Moreover, we've added rules make it even easier to keep on track. For more expansive thoughts, you can turn to the back of the Bible for additional ruled pages.

In addition, this is the only available wide-margin Bible to feature the highly-regarded New Revised Standard Version translation, the preferred translation in most academic settings, as well as many churches and homes. So whether you're a student or professor, pastor or lay person, The NRSV Notetaker's Bible will fit your Bible study needs. Its open margins are a perfect match for your open mind.

The NRSV Notetaker's Bible is available in hardcover as well as in deluxe cloth and bonded leather, ideal for presentations and gift giving.

Here is a view of a page spread (click image for actual size):

I’d prefer a page without the ruled lines, but maybe that’s just me.

HT: Jay Davis

New Journaling Bibles on the Horizon (HCSB, NRSV)

There are two new editions in the HCSB, called the HCSB Notetaker’s Bible, set for release very soon (October 8). One is referred to as a Men’s edition (ISBN 158640475X) and comes in a decorative brown hardcover. A women’s edition in mauve/olive green is also available (ISBN 1586404768).

There are no page spreads available for viewing yet, but these images of the covers are available at the CBD website (click on each image to see each Bible’s respective page):

Really, B&H should have probably avoided calling these “Men’s” and “Women’s” editions. I’m certain there will be some women who want the brown, and you never know who might want the other edition as well.

The CBD website also includes the following ad copy:

In an age when people can take notes using a variety of electronic media, there has emerged a countertrend whereby people want to journal in their won handwriting. The Notetaker's Bible features wide margins with subtle ruled lines, helpful center-column cross references, a concordance, and best of all, the largest point size among all Bibles of this kind. Handsomly bound for a man's taste. [The women’s edition says “Beautifully bound in with a woman's taste in mind.”]

Features include:

- The largest point size among Bibles of this kind

- Easy-to-navigate center-column references

- An easy-to-use concordance

- Ribbon marker

- Words of Jesus in red

- Translation footnotes, and exclusive HCSB bullet notes

Both Bibles measure 9.38 x 7.25 x 1 and contain 1280 pages. Biblical text will be presented in double columns. Personally, I feel that if a Bible of this sort uses double columns of text, there should be equal amounts of spacing for written notes for each column. We will have to see if B&H Publishing thought of this.

While I was on the CBD website, I also noticed an NRSV Notetaker’s Bible (ISBN 0195289226) to be released from Oxford University Press in 2009. There aren’t a lot of details yet, and no image that I could find even of the cover. But according to the CBD site the Bible will be paperback, contain 1296 pages, and measure 8 x 6.3 inches.

Worthy of Note 01/30/2008

Says Iyov:

So, with all that extra page space, there is plenty of room for making ample annotations. The paper is significantly thicker than typical Bible paper, so there is much less bleed through from a pen. And, I can add extra paper anytime one wants (in the fashion of Jonathan Edwards' Blank Bible). If I make a mistake, I can always remove the page and replace it with a photocopy from my bound edition of the NOAB. If I want to slip in an entire article, or a copy of a page in original languages -- there is no problem. It seems to me that this is the ultimate in flexibility.

I'm glad to see this finally released, although I doubt I'll personally buy one. Regardless, I've got a number of larger blog projects I'm working on, one of which is an update to last year's survey of wide-margin Bibles. I'm glad that I'll be able to include an entry for the NRSV this year.

But we find ourselves at a point in history when we've never had so many choices, and yet the options are mostly arrayed along a horizontal spectrum -- a thousand different flavors of the same basic thing. I'd like to see more vertical choices, and that might require a shift in perspective. Instead of speaking to end-users as consumers, we might have to start thinking of them as readers.

What is most significant in the post is Bertrand's five-point "Starting Points for Marketing High-End Bible Editions." I can only hope that publishers will pay attention.

My esteem for White dropped significantly a few years ago due to the way he handled a theological disagreement with another individual whom I respect very much. I felt his approach to the issue was uncharitable, far too public, and lacking in the kind of collegiality that should characterize Christian scholarship. Nevertheless, White is usually in natural form when he is engaged in formal debate. However, I often believe that White is rarely pitted in his debates against opponents who are equally skilled. At the very least, Ehrman should provide a worthy opponent to White and this is a subject in which both are well-versed.

Christianity Today has released its list of the "10 Most Redeeming Films of 2007." Some entries on the list may surprise you, but it's a very good list. I remember when we used to do more movie reviews and discussion around here.

Finally, in the I JUST DON'T GET IT DEPARTMENT: 2008 marks the 30th anniversary of the New International Version of the Bible. I've seen references on two other blogs (see here and here; oh, and also here) that Zondervan is planning a special wide-margin, high-end leather edition of the NIV Study Bible as one of the many ways that the NIV's 30th anniversary will be celebrated.

This is in spite of the fact that so many of us have asked for one decent wide-margin edition of the TNIV (the so-called TNIV Square Bible is flawed in three areas: (1) it's paper is too thin for annotations because it is a thinline, (2) the user doesn't have wide margin access to the inner column of text, and (3) the binding is subpar). If the TNIV is truly an improvement to the NIV (which I honestly believe it is), then why does Zondervan (and IBS, Cambridge, and Hodder) keep pushing the NIV and publishing new editions? If in ten years the TNIV turns out to be an also-ran translation, it will only be because publishers didn't know how to fully transition away from the NIV.

My suggestion for celebrating the NIV's 30 year anniversary? Retire it. (My apologies to everyone I just offended, including my friends at Zondervan.)

I would like to find simply ONE decent wide-margin, high quality (see Bertrand's post above for the meaning of high-quality) Bible in a contemporary 21st century translation (HCSB, NLTse, TNIV, or NET). I'm still writing down notes in my wide margin NASB95, but the first translation of those I've listed that is released in a single-column, non-thinline, wide-margin edition, I will make my primary translation for preaching and teaching for the next decade. You heard it here first.

Top Ten Bible Versions: The Honorable Mentions

In hindsight, I don't know if the "Top Ten" designation was all that accurate because these aren't the ten Bibles I use the most. But in addition to the first few which I actually do use a good bit, I also wanted to introduce a few other translations that have stood out to me over the past couple of decades since I began collecting them. There are a few other Bibles that were contenders for such a list. I thought that I could briefly mention them in this follow up post.

King James Version.

I would imagine that if most people put together a top ten list, the KJV would be on it. I almost included it, but it seemed too predictable. Plus, I'm in no position to necessarily write anything new on the KJV (not that my other posts were wholly original either). Nevertheless, the KJV does deserve recognition because no other English translation has held the place of prominence that it has in the history of translations. It is still used today as a primary Bible by millions of Christians, still ranks somewhere in the top three positions of sales in CBA rankings, and even for those who have moved onto something newer, it is still the translation that verses have been memorized in like no other version.

I predict this is the last generation in which the KJV will still receive so much attention, but I have no trouble saying I may be wrong. It's difficult to say that one can be reasonably culturally literate--especially when it comes to the standards of American literature--without a familiarity of the KJV. Nevertheless, I cannot in good judgment recommend the KJV as a primary translation for study or proclamation because its use of language is too far removed from current usage. I don't mean that it's entirely unintelligible--not at all. But a primary Bible should communicate clear and understandable English in keeping with the spirit of the Koiné Greek that the New Testament was written in. I also cannot recommend it as a primary Bible because of the manuscript tradition upon which it rests. There's simply too much that has been added to the text. It was certainly the most accurate Bible in its day, but this is no longer true. My exception to this, however, is that I do find the KJV acceptable for public use with audiences made up primarily of senior citizens since this was exclusively their Bible. And the KJV still seems to be appropriate for use in formal ceremonies including churches and weddings--although I have not recently used it for such.

There is some confusion on what is actually the true King James version. Most do not realize that the average KJV picked up at the local book store is not the 1611 edition, but rather a 1769 fifth edition. And the reality is that there are numerous variations of this out there. For those who want a true and unadulterated KJV, the recently released New Cambridge Paragraph Edition seems to be the one worth getting.

The NET Bible.

The NET Bible is one of about four translations (including the ESV, NRSV, and KJV) of which I received the most emails asking why it wasn't included in my top ten. The primary initial reason for the NET Bible's exclusion was simply that I had not spent enough time with it. I made the unfortunate decision to purchase a "2nd beta edition" only a few weeks before the final first edition came out (of which I recently obtained a copy).

Everyone I've heard speak about the NET Bible has high remarks about the 60K+ notes that come with the standard edition. And I can honestly say that these notes have become a regular resource for me when I study a passage. I don't hear as much high praise for the translation itself, though I don't hear anything particularly negative about it either. In general, though, I do recommend the NET Bible. I really like the editions I've seen made available--not just the standard edition, but also the reader's edition, and the Greek/English diglot which I'm very impressed with. The notes in the diglot are a slightly different set than what is in the standard edition. The "ministry first" copyright policy and the ability to download the NET Bible for free from the internet are very commendable on the part of its handlers.

I'd like to see the NET Bible get more attention, and I'd like to see more people introduced to it. I'm not sure it will get the widespread attention it deserves as long as it can only be obtained through Bible.org. In spite of the fact that my top ten series is over, I am going to continue to review translations, and the NET Bible will probably receive my attention next. But we have to spend some quality time together first.

The Cotton Patch Version.

I decided not to include a colloquial translation in my top ten, but if I had, the Cotton Patch Version of the New Testament would have held the category. Most colloquial translations are fun, but a bit gimmicky. The Cotton Patch Version rendered from the Greek by Clarence Jordan was anything but gimmicky. During the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960's, Jordan recast the events of the New Testament in the Southern United States. Replacing Jew and Gentile with "white" and "negro," and status quo Judaism with Southern Baptists (of which he was one), Jordan clearly brought the radical message of the New Testament into current contexts. The Cotton Patch Version is certainly fun reading if you are familiar with Bible Belt southern locales, but more importantly, the message is gripping as well.

The New Revised Standard Version.

The NRSV is an honorable mention I've added since I first announced the series. Originally, I felt like the NASB represented both the Tyndale tradition and formal equivalent translations well enough, plus at the time my use of the NRSV had become quite rare. Then my little NASB vs. NRSV comparison that I wrote with Larry revived my interest in the NRSV, and I now even have a copy sitting on my desk.

A year ago, I would have thought that the NRSV had seen its last day in the Bible version spotlight--except for academic use, but it seems to have had a bit of a renaissance with new attention and even new editions being published. It is still the translation of choice for the larger biblical academic community, primarily in my opinion because it has the widest selection of deutero-canonical books available of any translation. In its early days the NRSV was also embraced by many in the evangelical community but such enthusiasm seems to have waned. I think than rather than fears of theological bias, evangelical readers simply have too many other versions to choose from since the release of the NRSV.

Yes, the NRSV may be a few shades to the left of evangelical translations, but I've spent enough time with it to state clearly that it is not a liberal Bible. Don't let sponsorship from the National Counsel of Churches drive you away. If that were the only factor in its origin, I'd be skeptical, too, but the fact that Bruce Metzger was the editorial head of the translation committee gives me enough confidence to recommend it--if for nothing else, a translation to be read in parallel with others.

Well, is the series done? Not quite yet. I'll come back later this week with a few concluding thoughts about the list and the current state of Bible translations in general.

GUEST REVIEW: The New Oxford Annotated Study Bible (3rd Edition)

Below is a guest review from This Lamp reader, "Larry."

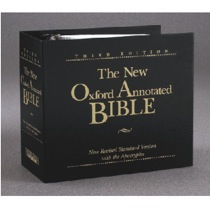

The Benchmark: the New Oxford Annotated Study Bible (3rd Augmented Edition)

A recent post by Rick described the debate in Muscogee County, Georgia over which translation to use in a public high school Bible class. The superintendent of the school was described as leaning towards the New King James Version – an odd choice for a secular setting, an odd choice for a setting desiring the latest scholarship, an odd choice for a high school class. But imagine that you were designing a college course to be taught in a secular school on the Bible. Which version would you use?

The New Oxford Annotated Study Bible (NOAB) aims to fulfill this role by being (as declared on the cover) an “ecumenical study Bible.” (An unfortunately ambiguous phrase – the Bible does not advocate ecumenicism, but rather is meant to be used equally by the various Protestant, Catholic, other Christian, and even in Hebrew Scriptures, by Jewish readers.) It includes not only annotations and book introductions, but a variety of helps (brief essays, maps, and glossary) appropriate to an academic audience. Although it is printed on bible paper and has rather better binding than a typical textbook, this book otherwise screams I am a college textbook in one’s hand. And as such, it was wildly successful, quickly becoming the standard text for academic Bible classes. And it became something of a standard reference for those interested in academic-style self study.

But does the NOAB deserve this praise? This pioneer has come under attack from all directions: there are a variety of new, more heavily annotated study Bibles available; it has been attacked for a leftward turn in its most recent editions; and it no longer seem as ubiquitous as it once was. What has happened to the NOAB? This review will explore the most recent edition, the Third Augmented, of the New Oxford Annotated Bible.

Acronyms

This is the second of my reviews of academic (and a few faith-oriented) study Bibles. Here is a brief list of versions I plan to cover together with acronyms I use.

JSB: Jewish Study Bible (Oxford 2004) [NJPS]

NOAB: New Oxford Annotated Study Bible (3rd Augmented Edition) (Oxford 2007) [NRSV]

NISB: New Interpreter’s Study Bible (Abingdon 2003) [NRSV]

HSB: HarperCollins Study Bible (2nd edition) (Harper San Francisco 2006) [NRSV]

CSB: Catholic Study Bible (2nd edition) (Oxford 2006) [NAB]

OSB: Oxford Study Bible (Oxford 1992) [REB]

WSP: Writings of St. Paul (2nd edition) (Norton 2007) [TNIV]

ECR: Early Christian Reader (Hendrickson 2004) [NRSV]

TSB: TNIV Study Bible (Zondervan 2006) [TNIV]

OSBNT: Orthodox Study Bible: New Testament and Psalms (Conciliar Press Edition) (Conciliar Press 1997) [NKJV]

Readers may want to look back at my first review in which I discussed the framework for analysis and specifically mentioned that I find the terms “liberal” and “conservative” unhelpful and ambiguous when evaluating study Bibles.

An overview of the NOAB

The New Oxford Annotated Study Bible, 3rd Augmented Edition

Michael Coogan, editor

Marc Z. Brettler, Carol A. Newsom, Pheme Perkins, Associate Editors

Translation: New Revised Standard Version

Hebrew Scriptures: yes

Deuterocanon: yes

Christian Scriptures: yes

Current Amazon price: $28.35

xxvii + 1375 Hebrew Bible + 383 Apocrypha +640 New Testament & extras + 2181 + 32 map pages

Extras:

Medium length introduction to books and major sections

60 black and white diagrams and maps

32 page color map section, with 14 large color maps.

Listing of biblical canons

Index and map index

Hebrew calendar discussion

Timeline (Egypt/Israel/Syria-Palestine/Mesopotamia)

Chronology of rulers in Egypt/Assyria/Syria/Babylonia/Persia/Roman Empire/Israel

Table of weights and measures

Listing of parallel texts (synoptic passages) in the Hebrew Scriptures, Apocrypha, and New Testament

Glossary of terms (15 pages)

Bibliography of translations of primary sources

Concordance (66 pages)

72 pages of additional essays

The editors of the volume are

- Michael Coogan (Stonehill Coll.) a former faculty member at Harvard, Michael Coogan for many years served as the director of the Semitic Museum’s publication program. He still maintains a relationship with Harvard Museum. He is well known as a biblical archaeologist. He was involved as a critical reviewer of both the 1991 and 1999 editions of the Catholic New American Bible (whose translation team includes some Protestant scholars.)

- Marc Zvi Brettler (Brandeis) who holds a named chair and chairs the Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies. He was co-editor of the JSB, the author of a major textbook on Biblical Hebrew, and is well known for his teaching, which is reflected in a very nice volume he wrote called How to Read the Bible. He is a strong advocate of what he calls “Jewish sensitive” readings of the Bible.

- Carol Newsom (Emory) a faculty member at the Candler School of Theology, the author of several commentaries on Job, and co-editor of the Women’s Bible Commentary. She also actively participates in the Episcopalian Church USA.

- Pheme Perkins (Boston Coll.) is best known for her work in early Christianity. She is a former president of the Catholic Bible Association and is also active in the Society for Biblical Literature.

Notes on the NRSV translation

The NOAB, like many leading academic study Bibles (HSB, NISB, ECR) uses the NRSV translation – a translation that is probably familiar to most of the readers of this blog. The NRSV is popular because it is a moderately formal translation, has the widest degree of acceptability among different denominations, is derived from the dominant strand of English Bible translations (the Tyndale/KJV tradition), and includes the Catholic and Orthodox deuterocanon/apocrypha. The translation is strikingly different in how it treats the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures – the Hebrew Scriptures are translated into more formal language than the Christian Scriptures, reflecting their different source material. The translators explain,

The NRSV also attempts, particularly in the Christian portions, to use inclusive language when context dictates that was the original meaning in the Greek. The translators explain,“Another aspect of style will be detected by readers who compare the more stately English rendering of the Old Testament with the less formal rendering adopted for the New Testament. For example, the traditional distinction between shall and will in English has been retained in the Old Testament as appropriate in rendering a document that embodies what may be termed the classic form of Hebrew, while in the New Testament the abandonment of such distinctions in the usage of the future tense in English reflects the more colloquial nature of the koine Greek used by most New Testament authors except when they are quoting the Old Testament.”

“Paraphrastic renderings have been adopted only sparingly, and then chiefly to compensate for a deficiency in the English language—the lack of a common gender third person singular pronoun. . . . The mandates from the Division [of Education and Ministry of the sponsoring organization, the National Council of Churches] specified that, in references to men and women, masculine-oriented language should be eliminated as far as this can be done without altering passages that reflect the historical situation of ancient patriarchal culture. As can be appreciated, more than once the Committee found that the several mandates stood in tension and even in conflict. The various concerns had to be balanced case by case in order to provide a faithful and acceptable rendering without using contrived English. Only very occasionally has the pronoun “he” or “him” been retained in passages where the reference may have been to a woman as well as to a man; for example, in several legal texts in Leviticus and Deuteronomy. In such instances of formal, legal language, the options of either putting the passage in the plural or of introducing additional nouns to avoid masculine pronouns in English seemed to the Committee to obscure the historic structure and literary character of the original. In the vast majority of cases, however, inclusiveness has been attained by simple rephrasing or by introducing plural forms when this does not distort the meaning of the passage. Of course, in narrative and in parable no attempt was made to generalize the sex of individual persons.”

In part because of this practice, a number of traditionalists prefer the use of the NRSV’s predecessor, the RSV – and Oxford has accordingly kept older editions of the New Oxford Annotated Bible based on the RSV in print.

Publication History of the NOAB

The NOAB is the latest in a long line of editions:

- 1962: The original Oxford Annotated Bible. Editors: Herbert May (Oberlin/Vanderbilt) and Bruce Metzger (Princeton). The version had the flavor of an “official annotated” version of the RSV – May and Metzger were the Chair and Vice-Chair of the RSV contributions were received from the chair of the RSV committee (Luther Weigle, Yale). Metzger was a leading Evangelical figure of his time.

- 1965: Revised edition of The Oxford Annotated Bible with Apocrypha. Editors: May and Metzger. This edition – not just the translation – but the annotated edition – received the imprimatur from Richard Cardinal Cushing of Boston.

- 1973: A major revision – (first edition of) The New Oxford Annotated Bible [editions appeared with and without Apocrypha.] Editors: May and Metzger. The contributors stayed the same as in the 1965 edition.

- 1977: The New Oxford Annotated Bible with Apocrypha, Augmented Edition. Editors: May and Metzger. This version included the newly translated 3 and 4 Maccabees and Psalm 151. This version received the approval of approval of Athenagoras (Greek Orthdox Archbishop of Thyateira and Great Britain, and a well-known supporter of the ecumenical movement). For many traditionalists, this was the high point of this series.

- 1991: The New Oxford Annotated Bible, Second Edition [editions appeared with and without Apocrypha.] Editors: Metzger and Roland Murphy (Duke). Roland Murphy, a Catholic priest, was well known for a variety of contributions to Biblical Studies. This edition featured a major change – it was based on the NRSV. The notes were moderately revised from the 1977 edition. A concordance was added. More controversially, the traditional two-column translation/one-column note format was abandoned for a two-column translation/two-column note format. And unfortunately, the various accents and pronunciation guides found for proper nouns in the earlier edition were abandoned, a feature that was not reappear in later editions.

- 2001: The New Oxford Annotated Bible, Third Edition [editions appeared with and without Apocrypha]. Editors: Coogan, Brettler, Newsom, Perkins. This was far beyond an ordinary revision of the Second Edition – it was a largely new rewrite. Almost every sentence was changed (except the underlying NRSV translation). A concordance was added, and the volume was larger than previous editions in every dimension. The typesetting was improved (and the format reverted to the older two-column translation/one-column note format was used). By this point, the edition was facing serious competition in the college market from the first edition of the HSB; and Oxford production team made a serious effort to fight back, and made the most easily readable version in the series to date (striking at the one of the HSB’s main weakness – its terrible physical design). Book introductions were much longer; annotations were longer (and featured more complete sentences); and far more contributors participated in the notes.

- 2007: The New Oxford Annotated Bible, Third Augmented Edition [so far only the edition with Apocrypha has appeared, although an edition without Apocrypha is promised.] Editors: Coogan, Brettler, Newsom, Perkins. This was a very minor update to the Third Edition; a few new black and white maps, charts and diagrams were included (put in at the end of books so the pagination remains the same), the book and section introductions had minor rewritings, and a useful glossary was added (which drew heavily on the glossary that had previously appeared in the JSB). Amusingly, the Oxford production team forgot to update the copyright page correctly (at least in the first printing.)

Review of the NOAB

As I begin to review the NOAB’s annotations think an academic study Bible is likely to see three major uses:

- As a classroom text (here my advice is least meaningful, since a student is likely to have to choose the study Bible chosen by the class instructor)

- For self-study As a reference source.

Now, I will reveal my punchline in advance: in this review and my next two reviews, I will rank the three NRSV study Bibles as follows

- Best for classroom use: NOAB

- Best for self-study: NISB

- Best for reference: HSB

Where did the annotations come from? The NOAB involves a much broader group of people involving much wider range of opinions than previous editions. The diversity can be seen from the range of different annotators – who reflect participants from a variety of theological backgrounds (Jewish, Mormon, Evangelical, Episcopalian, Mainline Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox) and a variety of different cultural backgrounds. This sort of diversity is in line with contemporary academic trends, and reflects the widely held belief that the academy – even in theological studies, should mirror society at large.

- Theodore Bergren (U. of Richmond): 2 Edras

- Mark Biddle (Baptist Th. Sem.): Jeremiah, Letter of Jeremiah, Baruch

- Joseph Blenkinsopp (Notre Dame): Isaiah

- M. Eugene Boring (Texas Christian U.): 1 Peter

- Sheila Briggs (USC): Galatians

- Mary Chilton Callaway (Fordham): 1 & 2 Maccabees

- David Carr (Union Th. Sem.): Genesis

- John Collins (Yale): 3 Maccabees

- Stephen Cook (Virginia Th. Sem.): Ezekiel

- Linda Day (editor, Catholic Biblical Quarterly): Judith

- F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp (Princeton): Lamentations, Song of Solomon

- Neil Elliott (adjunct faculty at United Th. Sem., Twin Cities, acquisition editor at Fortress Press): Romans

- Tamara Cohn Eskenazi (Hebrew Union Coll./Jewish Inst. Religion, Los Angeles): Ezra-Nehemiah, 1 Esdras

- Cain Hope Felder (Howard U.): James

- Obery Hendricks (New York Th. Sem.): John

- Richard Horsley (U. Mass., Boston): Mark, 1 Corinthians

- Cynthia Briggs Kittredge (Episcopal Th. Sem. Southwest): Hebrews

- Gary Knoppers (Penn. State): 1 & 2 Chronicles

- John Kselman (St. Patrick’s Sem.): Psalms, Psalm 151, Prayer of Manasseh

- Mary Joan Winn Leith (Stonehill Coll.): Ruth, Esther, Greek Esther, Jonah

- Amy-Jill Levine (Vanderbilt): Tobit, Daniel, Additions to Daniel

- Bernard Levinson (U. Minnesota): Deuteronomy

- Jennifer Maclean (Roanoke Coll.): Ephesians, Colossians

- Christopher Matthews (Weston Jesuit Sch. Th.): Acts

- Steven McKenzie (Rhodes Coll.): 1 & 2 Samuel

- Margaret Mitchell (U. Chicago): 1 & 2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon

- Gregory Mobley (Andover Newton Th. Sch.): Book of the Twelve (except Jonah)

- Carolyn Osiek (Texas Christian U.): Philippians

- Andrew Overman (Macalester Coll.): Matthew

- Pheme Perkins (Boston Coll.): 1, 2, 3 John

- Iain Provan (Regent Coll.): 1 & 2 King

- Jean-Pierre Ruiz (St. John’s U.): Revelation

- Judith Sanderson (Seattle U.): Exodus

- Leong Seow (Princeton): Job, Ecclesiastes

- Abraham Smith (): 1 & 2 Thessalonians

- Marion Soards (Louisville Presbyterian Th. Sem.): Luke

- Patrick Tiller (unaffiliated): 2 Peter, Jude

- Sze-kar Wan (Andover Newton Th. Sem.): 2 Corinthians

- Harold Washington (St. Paul Sch. Th.): Proverbs, Sirach

- Walter Wilson (Emory): Wisdom of Solomon, 4 Maccabees

- David Wright (Brandeis): Leviticus, Numbers

- Lawson Younger (Trinity Int’l U.): Joshua, Judges

While this list certainly contains many distinguished names, one cannot help but notice that the list of participants is not quite as distinguished on average as the participants in earlier editions. However, the annotations are far more detailed. As an example, consider the annotations in the NOAB of the first chapter Ezekiel (more exactly, Ezekiel 1:1-28a.) First, I’ll compare these with the first edition of the New Oxford, and then with some other study Bibles.

NRSV: [1] In the thirtieth year, in the fourth month, on the fifth day of the month, as I was among the exiles by the river Chebar, the heavens were opened, and I saw visions of God. [2] On the fifth day of the month (it was the fifth year of the exile of King Jehoiachin), [3] word of the Lord came to the priest Ezekiel son of Buzi, in the land of the Chaldeans by the river Chebar; and the hand of the Lord was on him there.

[4]As I looked, a stormy wind came out of the north: a great cloud with brightness around it and fire flashing forth continually, and in the middle of the fire, something like gleaming amber. [5] In the middle of it was something like four living creatures. This was their appearance: they were of human form. [6] Each had four faces, and each of them had four wings. [7] Their legs were straight, and the soles of their feet were like the sole of a calf’s foot; and they sparkled like burnished bronze. [8] Under their wings on their four sides they had human hands. And the four had their faces and their wings thus: [9] their wings touched one another; each of them moved straight ahead, without turning as they moved. [10] As for the appearance of their faces: the four had the face of a human being, the face of a lion on the right side, the face of an ox on the left side, and the face of an eagle; [11] such were their faces. Their wings were spread out above; each creature had two wings, each of which touched the wing of another, while two covered their bodies. [12] Each moved straight ahead; wherever the spirit would go, they went, without turning as they went. [13] In the middle of the living creatures there was something that looked like burning coals of fire, like torches moving to and fro among the living creatures; the fire was bright, and lightning issued from the fire. [14] The living creatures darted to and fro, like a flash of lightning.

[15] As I looked at the living creatures, I saw a wheel on the earth beside the living creatures, one for each of the four of them. [16] As for the appearance of the wheels and their construction: their appearance was like the gleaming of beryl; and the four had the same form, their construction being something like a wheel within a wheel. [17] When they moved, they moved in any of the four directions without veering as they moved. [18] Their rims were tall and awesome, for the rims of all four were full of eyes all around. [19] When the living creatures moved, the wheels moved beside them; and when the living creatures rose from the earth, the wheels rose. [20] Wherever the spirit would go, they went, and the wheels rose along with them; for the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels. [21] When they moved, the others moved; when they stopped, the others stopped; and when they rose from the earth, the wheels rose along with them; for the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels.

[22] Over the heads of the living creatures there was something like a dome, shining like crystal, spread out above their heads. [23] Under the dome their wings were stretched out straight, one toward another; and each of the creatures had two wings covering its body. [24] When they moved, I heard the sound of their wings like the sound of mighty waters, like the thunder of the Almighty, a sound of tumult like the sound of an army; when they stopped, they let down their wings. [25] And there came a voice from above the dome over their heads; when they stopped, they let down their wings.

[26] And above the dome over their heads there was something like a throne, in appearance like sapphire; and seated above the likeness of a throne was something that seemed like a human form. [27] Upward from what appeared like the loins I saw something like gleaming amber, something that looked like fire enclosed all around; and downward from what looked like the loins I saw something that looked like fire, and there was a splendor all around. [28] Like the bow in a cloud on a rainy day, such was the appearance of the splendor all around. This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord.

New Oxford, 1st ed.: 1:1-3:27: The call of Ezekiel. 1:1-3: Superscription. The thirtieth year, perhaps the thirtieth year after Ezekiel’s call, and if so, the date of the initial composition of the book, 563 B.C. (compare Jer. 36:1-2). Fifth day of the fourth month . . . , fifth year of the exile would be July 31, 593 B.C. This is reckoned from a lunar calendar, with the year beginning in the spring. The name Ezekiel means “God strengthens.” Chebar, a canal which is mentioned also in the Babylonian records, flowing southeast from its fork above Babylon, through Nippur, and rejoining the Euphrates near Erech. Hand of the Lord expresses Ezekiel’s sense of divine compulsion (3:14,22; 8:1; 33:22; 37:1; 40.1). 1:4-28a The throne chariot vision. Compare the imagery in 1 Kg. 22:19-22; Is. 6:1-9. 4: Out of the north, a literary figure drawn from Canaanite mythology, according to which the gods lived in the north. Stormy wind (1 Kg. 19:11), cloud (Ex. 19:16), and fire (1 Kg. 19:11-12) are all elements in the theophany (manifestation) of God. 5: The living creatures (Rev. 4:7) are cherubim, guardians of God’s throne (see Ex. 25:10-22; 1 Kg. 6:23-28), namely winged human-headed lions or oxen, symbolizing mobility, intelligence, and strength. 15-21: The four wheels (compare the four faces of the creatures) symbolize omni-direction mobility. 22: In ancient cosmology, the firmament separated the waters above the earth from the earth (Gen. 1:6-8). 26-28: Thus the Lord was enthroned above his creatures; compare the Lord enthroned above the cherubim in Ex. 37:9 (on the ark); 1 Sam. 4:4.

NOAB: 1:1-3:27: Part 1: The call of Ezekiel. 1:1-3: Superscription. Ezekiel was a Zadokite priest (v. 3, 44:15-31n.), steeped in the traditions of Jerusalemite royal theology (Zion theology; see Introduction). Despite his exile, he never loses his priestly role (cf. 43:12n.). The thirtieth year, probably Ezekiel’s own age. At the age for assuming his duties at the Jerusalem Temple (Num. 4:3), Ezekiel sought solitude outside his settlement (see 3:14-15) to reflect on what course his life might instead take in exile. Fifth day of the fourth month . . . fifth year of the exile would be July 31, 593 BCE. Chebar, a canal, flowing near Nippur, which is mentioned also in Babylonian documents. 3: The name Ezekiel means “God strengthens.” Hand of the LORD (3:14,22; 8:1; 33:22; 37:1; 40:1), Ezekiel undergoes the same sort of divine compulsions and ecstatic trances experienced by Israel’s early prophets, such as Elijah and Elisha (1 Kings 18:46; 2 Kings 3:15). Chaldeans, Babylonians. 1:4-28a: The throne-chariot vision. Cf. the imagery in 1 Kings 22:19-22; Isa 6:1-9. The first two-thirds of Ezekiel’s vision of God merely describes the creatures and wheels below the platform supporting God’s throne. In Ezekiel’s theology of God’s transcendence, God is clearly far removed from earthly perception. 4: Stormy wind . . . cloud . . . and fire are phenomena often associated with appearance of God in the Hebrew Bible (see Ps 18:8-12). Out of the north, because the shape of the Fertile Crescent meant that anything coming from Jerusalem arrived in Babylonia from the north. Something like, Ezekiel uses the word like to suggest the difference between his description and the transcendent reality itself. 5-14: The living creatures are identified as cherubim in a later vision (10:15,20), guardians of God’s throne (see Ex 25:18-22; 1 Kings 6:23-28), namely winged, human-headed lions or bulls. Uncharacteristically, the creatures Ezekiel sees have four faces (v. 10; cf. Rev 4:7). 13: Torches, cf. Gen 15:17. 15-21: The four . . . wheels (compare the four faces of the creatures) to God’s throne are a crucial element in Ezekiel’s reckoning of his central priestly belief that God had elected and now dwelled in Zion with the early Zion’s coming destruction by the Babylonians (see Introduction). Its wheels mean that the real, cosmic Zion-throne has omnidirectional mobility and is not tied down to earthly Jerusalem. See further 1:26-28n. 18: Full of eyes, symbolic of omniscience (10:12, Zech 4:10; cf. Rev 4:6,8) 22-25: A dome, referring to the cosmic firmament of Gen. 1:6-8, which separates earth and heaven. Jerusalem and its Temple mount symbolize the cosmic mountain where heaven and earth intersect at the dome. 26-28: Thus the Lord was still really enthroned atop the cosmos, even though Jerusalem, the symbol of God’s cosmic dwelling (Ps 26:8, 63:2, 102:16), was to be destroyed by the Babylonians. On the glory of the Lord, see 10:1-22n. Appearance of the likeness, the qualified language again emphasizes God’s transcendence and cosmic power (see 1:4n.). God’s self is three levels removed from Ezekiel’s description of God.

As we compare these two versions, we note several things. The later edition contains all the information in the former, but often explained somewhat more leisurely and simply. A few strange notes have been cleaned up (look at the notes to verse 4 – the “from the North” refers to Jerusalem, not to some Canaanite belief – the more recent version is actually the more respectful to the text. And words unlikely to be known by the average undergraduate, such as “theophany” are omitted (on the other hand, were the undergraduate using the earlier edition, she’d learn a new word.) The NOAB is much more effective at verses 26-28 at explaining some of the reasoning behind the vision of the chariot – the idea of a heavenly temple and heavenly Jerusalem. Thus rather than the earlier edition’s brief: “Thus the Lord was enthroned above his creatures,” the NOAB has a more meaningful discussion: “Thus the Lord was still really enthroned atop the cosmos, even though Jerusalem, the symbol of God’s cosmic dwelling was to be destroyed by the Babylonians.”

Recall my three evaluation criteria for academic study Bibles – as a classroom text, as a self-study guide, and as a reference. Here, I would argue that the newer edition, with its clearer explanations, was superior to the older editions as a classroom text and for self-study. But as a reference, perhaps it is a tie – the newer edition contains more material and is easier to understand, but the earlier edition included terse notes especially appropriate for someone who needs to extract information quickly and non-systematically.

Classroom value is further enhanced by the essays were written by the editors (those items in italics were section introductions)

- Brettler: Pentateuch, Historical Books, Poetical & Wisdom Books, Canons of the Bible (w/Perkins), Hebrew Bible’s Interpretation of Itself, Jewish Interpretation in the Premodern Era

- Coogan: Textual Criticism (w/Perkins), Interpretation of the Bible: From the Nineteenth to the Mid-twentieth Centuries, Geography of the Bible, Ancient Near East

- Newsom: Prophetic Books, Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, Christian Interpretation in the Premodern Era, Contemporary Methods in Biblical Study, Persian & Hellenistic Periods

- Perkins: Gospels, Letters/Epistles, Translation of the Bible into English, New Testament Interprets the Jewish Scriptures, Roman Period

An instructor can simply assign these essays, as well as the introductions to individual books, to a class – while I am not certain they would be sufficient reading for a challenging class, they certainly form a starting point. The essays are clear enough, albeit not particularly inspired.

Now, for the sake of discussion, let’s compare the NOAB’s annotations with those of the leading competitors, starting with HarperCollins Study Bible (HSB):

HSB: 1:1-3:15 Ezekiel’s inaugural vision, which may be compared with shorter, though similar, accounts in Isa 6; Jer 1. God calls Ezekiel to act as a prophet and provides him with instructions about fulfilling this task. Other vision reports are in 8:1-11:25; 37:1-14; 40:1-48:35. 1:1-3 The book’s introduction places the prophet in Babylonia and dates his activity by reference to a Judahite king, Jehoiachin, now in exile. 1:1 Thirtieth year, probably Ezekiel’s age when he experienced this vision. The river Chebar, a canal, not a natural river, near Nippur. 1:2 Jehoiachin, Ezekiel, and others were exiled to Babylon in 597 BCE. The fifth year of the exile would have been 593. This is the first of thirteen such chronological notices (1:2; 8:1; 20:1; 24:1; 26:1; 29:1; 29:17; 30:20; 31:1; 32:1; 32:17; 33:21; 40:1). 1:3 The priest, either Ezekiel or Buzi, though most probably Ezekiel. Ezekiel is defined as a priest because of his lineage, whereas he becomes a prophet because of this visionary experience. The land of the Chaldeans, the plains of southern Mesopotamia, associated with an Aramean-speaking people who had entered this area earlier in the first millennium BCE. The hand of the Lord, a phrase indicative of a spirit possession; cf. 3:14-21; 8:1; 3:22; 37:1; 40:1. This phrase is present at the beginning of each of Ezekiel’s four vision reports. 1:4-28 Ezekiel encounters God. The combination of cloud, fire, creatures, the spirit, and wheels makes it impossible to reduce this vision to some readily understandable phenomenon. 1:4-14 Ezekiel perceives strange creatures. 1:4 Fire and cloud are often associated with the appearance of the deity (e.g., Ps 18). Something like gleaming amber, also in 8:2. 1:5 The author uses like (see also vv. 22, 26, 27) to emphasize the vision is proximate. The prophet does not actually see the deity and his accoutrements. The living creatures are part animal, part human, with the latter dominant, i.e., they have two legs and stand upright. Such winged creatures with animal features are related to the seraphim in Isa 6, another “prophetic call” narrative. Ancient Near Eastern mythology knows such creatures, often minor deities, some of which support the divine or royal throne. Cf. 10:15, 20, where similar creatures are labeled cherubim. 1:7 Bronze, also in the description of a man in 40:3. 1:10 Four faces (human, lion, ox, eagle) on one head is otherwise unattested. The imagery may emphasize alertness: as the wheels turn, the creature will be able to look in any direction. 1:12 The spirit, not the deity, but the spirit of the living creatures in v. 21 (see also v. 20; 3:12.) 1:13-14 The creatures are associated fire or lightning; cf. Gen 3:24 for an analogous creature who brandishes a flaming sword; Gen 15:17, where torches symbolize the presence of the deity. 1:15-21 Crystalline wheels associated with the creatures. Although the writer mentions a wheel (v.15), there are apparently four wheels, one for each creature. Either a chariot with four wheels on one axle (two wheels on each side of the carriage) or a ceremonial cart with two axles (and two wheels per axle) may be presumed in this description. The imagery of wheels emphasizes that the glory of the Lord (v. 28) was capable of movement. The motif of wheels symbolizes the mobility of the deity who will later leave the temple (10:18-19). 1:18 Full of eyes implies the ability see everything (cf. 10:12; Zech 4:10). 1:22-25 Below the dome. 1:22 Dome, the heavenly vault (see Gen 1:7-8). 1:24 Auditory imagery (e.g., like the thunder) rather than visual imagery, fire and light, prevails. Both sound and visual imagery attend the appearance of the deity (e.g. Ex 19:16-19). The sound of mighty waters. Cf. 43:2. In Rev 14:2, the sound is further defined in association with thunder. 1:25 A voice, or “a sound,” from above the dome indicates that even the deafening roar created by the creatures’ wings under the dome is not the ultimate sound. 1:26-28 Above the dome. The throne above the heavenly vault signifies the throne or council room of the deity. The deity enthroned in the heavens truly transcends the temple. Like, used ten times in three verses to emphasize that Ezekiel does not actually see the deity. Sapphire. Cf. Ex 24:10. Like a human form begins the description of the deity above the loins (waist) like amber, below the loins like fire. 1:28 Rather than proceed with a more detailed and hence dangerous description, the author moves to an analogy, the splendor of a rainbow, and the summation This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord, which again emphasizes that the prophet did not see God directly (see note on 1:5).

This excerpt makes clear why the HSB was such a threat to the dominance of the NOAB – it contains substantially more detail and explanation. Still, the explanation is better at the verse level than at the passage level: it is highly repetitive (the annotator mentions repeatedly that Ezekiel did not actually see God) and still misses the main point of the vision (as explained in the NOAB) – namely the enthronement of God above the dome while Jerusalem falls. For these and other reasons which I will detail in my next installment, this study Bible is perhaps not quite as well suited for classroom use; although it is certainly a highly useful reference. (I should also mention that there were two typographical errors in the HSB annotations that I corrected in my extended quotation above – it is not a particularly carefully proofread edition.)

Next, I turn to the version in yet another competitor to the NOAB, the New Interpreter’s Study Bible (NISB), not to be confused with the well-known multi-volume set. Let’s see how it handles this passage. However, because of the great length of the NISB, I only quote here from the sections dealing up to verse 3:

NISB: 1:1-3:27 Ezekiel’s prophetic call stands boldly at the beginning of the book, declaring the Lord as the agent of history and Ezekiel as the responsive steward of the divine word. After a short introduction that sets Ezekiel firmly in time and space (1:1-3), the first chapter offers glimpses of Ezekiel’s enigmatic vision (1:4-28a). Ezekiel’s response (1:28b) leads to his commissioning, which unfolds in several divinely scripted scenes: commissioning (1:28b-3:11), preparation (3:12-15), instructions (3:16-21), and inauguration (3:22-27). 1:1-3 The double introduction (vv. 1, 2-3) answers several implied questions: Where are we? What is wrong? What is the remedy? The Lord provides a vision and speaks a word to a refugee community in the enemy’s land that challenges their cherished theological assumptions and empowers them to re-imagine their identity and mission. In the NT, 1 Pet 1:1, 2:11 reinterprets exile as a disengagement from dominant culture. 1:1 This autobiographical narrative reports on visions of God (only in Ezekiel; see also 8:3; 40:2). The divine perspective is opened as Ezekiel sees behind the scenes to glimpse the mystery of divine presence and absence. The thirtieth year refers either to Ezekiel’s birth (see also the induction of priests in their thirtieth year, Num 4:30) or to Josiah’s discovery of the scroll in the temple (2 Kgs 22). 1:2-3 A third-person narrator now identifies Ezekiel as a priest controlled by God’s hand. In 593 BCE, Ezekiel is commissioned to mediate the divine word that comes to him in a land considered unclean and, through him, to those who have lost everything.

This passage illustrates well the strengths and weaknesses of the NISB. On the one hand, the annotations are written in a much more conversational style than those of the NOAB or the HSB. On the positive side, one can simply read this study Bible as if it were the transcript of a lecture of a friendly instructor. But on the other hand, it speaks throughout (especially in this passage) in the language of social justice, which may be somewhat disconcerting to many readers; and it sounds more than a little like an excerpt from a sermon (e.g., the gratuitous reference to 1 Peter.) In fact, this particular passage is not representative of the annotations of the NISB – the politics are somewhat more dilute in the full text, although they are there. But the overall effect is somewhat anachronistic – and surprisingly applied – this is clearly a Christian reading of the Bible – seeking to answer the question “what is the relevance of this passage to us today?” If one is comfortable with the framework in which these annotations teach, then this is an ideal study Bible for self-study, since it considers simultaneously thematic issues as well as issues at the verse level.

One thing which surprises me about all of the above study Bibles is that they interpret this highly mystical of passages in terms of allegory – or, in the case of the NISB, in terms of societal needs. This surprises me, since a mystical experience is by definition that of an individual – here, as much as any place in the Bible, we have the experience of mysticism from the viewpoint of a prophet himself. The NISB’s reading here is most dissonant with this mystical aspect – it reads what is ultimately an individual (psychological) experience in sociological terms. However, the NISB also reflects the better angels of the Christian tradition, in refusing to miss a chance to learn a moral lesson from a Biblical verse, and ultimately showing the selflessness of the pure Christian worldview.

I will mention here briefly one additional study Bible: Oxford’s Jewish Study Bible (JSB) – see my previous review. This version has such extensive annotations that the annotations for this passage exceed in length the annotations for the NOAB, HSB, and NISB combined, so I will not quote from it here. Instead, I will simply mention that it discusses, alone among these study Bibles, the mystical aspects of Ezekiel’s vision, and also relates it to non-canonical works such as 3 Enoch, as well as covering both the connections with Ancient Near Eastern traditions as well as its allegorical meaning.

Layout and physical design: Oxford University Press produces excellent Bibles – perhaps among major publishers only Cambridge University Press produces nicer Bibles. One of my old editions in this series stayed with me for years, suffering daily abuse, and it stood up surprisingly well to such regular use. The newer NOAB is larger, and has a glossy hardcover (it is also available in bonded leather edition) but the binding is excellent. The typography and print has never been clearer than it is in the third edition – the print is relatively large – larger than any of its NRSV competitors and the spacing in the notes is wide enough to make them easily readable. The paper is slightly translucent, but bleed through is limited and does not cause a problem (unlike the HSB).

A Leftward Turn?

There is something about Bibles that causes a certain sort of person to mutter about heresy. The NOAB has been criticized for being different than the Second Edition, and these charges rose to such a degree that Oxford University Press was forced to make a response :

What criticism in particular has been made against the NOAB? Well, a summary of the criticism can be found an article published by a conservative group. While the tone of the article speaks for itself, we can examine the claims it puts forwards:“This third edition of the classic New Oxford Annotated Bible represents not only a revision of a classic textbook and biblical reference work for the general reader, but nearly an entirely new book. . . . More Catholic scholars, a new group of Jewish scholars, more women, and scholars from a wider diversity of backgrounds (African-American, Latino, and Asian-American), joined the distinguished roster of contributors. The variety of interpretations, liberal and conservative, was increased. . . .

“There has been a focus in certain circles of Christian comment on these changes from traditional understanding. It is important to recognize that Oxford University Press is not aiming at influencing any current social or political trends, whether within secular society or within any church or denomination. The annotators and authors of the essays were given general instructions to guide them in writing their study materials, but except for specific indications of the length of their submissions, and the format in which they were to be submitted, they were left free to determine what they would comment on and how those comments would be shaped. The editorial board and Oxford staff reviewed every submission, and suggested numerous changes, but every revised version went back to the original author for acceptance or adjustment of the changes. No contributor was made to say anything with which he or she disagreed. It would have been impossible for one editor to impose a personal view or agenda on this process, and no editor attempted to do so. The views expressed in any of the annotations are the scholar's own, as that scholar understands the research of colleagues on the particular book of the Bible being commented on.”

- Claim: The NOAB is soft on homosexuality. I have found no passage in the notes that suggests that Bible permits homosexuality; indeed, the cited annotations make clear that homosexual behavior is unacceptable [Genesis 19:5 “disapproval of male homosexual rape is assumed here”; Romans 1:26-27 “Torah forbids a male ‘lying with a male as with a woman'"]. The comment on 1 Corinthians 6:9-11 appears to be making the same point (in a fashion appropriate for a textbook) that Rick made in this post.

- Claim: The NOAB denies Christ’s divinity. Given that belief in the divinity of Jesus is a central belief of Christianity, it would be quite surprising if this claim found support. Here, a single annotation in the book of John is quoted out of context, ignoring many other annotations which indicate that Jesus is divine in the book of John (e.g., the Introduction “It demonstrates that faith in Jesus is equivalent to faith in God . . . .”; 14:20 “their relationship with the risen Jesus will reflect the union of the Son with the Father.”

- Claim: The NOAB is soft on abortion. The claim is made that Psalms 139:13 is a prooftext for anti-abortion – I am frankly unconvinced of this reading; in any case, Jeremiah 1:5 is a much stronger notion (that God knew and selected the prophet before he was formed in the womb) and the annotation here is quite strong: “Knew, connotes a profound and intimate knowledge.”

- Claim: One NOAB editor has previously worked with member of a Christian outreach group to homosexuals. A claim is made that one of the editors worked on a project with a leader of a ministry group that reaches out to homosexuals. In an academic setting, I don’t feel it is appropriate to engage in such ad hominem attacks.

- Claim: The NOAB is infecting the Christian Mainstream. The claim is made that since the NOAB is the official text of the United Methodist Church’s Disciple Bible Study program. Of course, since this essay was published, the UMC’s publishing house, Abingdon, has produced its own study Bible, the NISB. As my quotation above showed, the NISB sometimes rather explicitly reflects a political agenda. In contrast, the NOAB is a much more neutral annotated text.

A claim is also made in the article that Bruce Metzger wrote “I have read your perceptive comments about the two editions of the Oxford Annotated Bible and am in full agreement with your evaluations.” Unfortunately, we don’t know exactly what evaluations Metzger is in agreement with; this comment appears to me to be taken out of context.

The disconcerting aspect for me is that in some ways the NOAB is a more traditional understanding of the Bible than earlier editions. The passage I analyzed above has in an early edition a reduction of Ezekiel’s experience of a wind from the North to Canaanite myth; in the current edition this is clearly explained as being from Jerusalem. While earlier editions a certain detached skepticism in earlier editions, the newer edition treats the philosophy of biblical inerrancy with much greater respect.

Nonetheless, the approach of this study Bible is historical-critical and it is not designed for devotional purposes. The NOAB’s contributors do reflect a diversity of views, including traditional views. Since the NOAB no longer has a “lock” on the study Bible market, if readers feel that it offends they have many other places to go. But to return to the question I started with, I know of no other study Bible as appropriate for a (secular) college classroom.

Final thoughts

The NOAB no longer looks as special as it once did: the contributors are in some cases less distinguished than their predecessors; and there is a wealth of different study Bibles to choose among. Still, the NOAB remains the most widely used study Bible in college classrooms and with good reason: the annotations are brief and insightful. One way in which it can be measured is that it serves as a benchmark: in marketing literature, publishers measure other academic study Bibles against the NOAB. While for many readers there might be a better alternative, one can certainly do worse than the NOAB. A person who reads it will have an excellent foundation in Biblical studies.

Coming up next: “The contender” – the HarperCollins Study Bible, 2nd edition.

Review: NRSV Standard Edition with Apocrypha [updated]

My experience with the NRSV has been primarily over a decade ago. When I went to seminary in the early nineties, it was the translation in vogue at SBTS. I picked up a hardback/pew copy in the campus bookstore (published by Holman no less!), and often used it in my papers. After taking some introductory language courses, I always found that it was more impressive to create my own translation in papers for biblical studies classes. However, in all other classes, that was practically looked down upon, so I always quoted the NRSV for those papers. I learned early on that since many of my teachers and graders were using the NRSV, my use of it often seemed in general to improve my final grade. I guess I had just enough psychology classes in my undergraduate studies to tweak the system to my own advantage.

Initially, the NRSV gained quite a wide acceptance with Evangelicals. Holman Bibles (the Southern Baptist Convention's Bible publisher) was a launch company along with Zondervan, Thomas Nelson and quite a few others. I even have a purple Life Application Bible in the NRSV! But at some point, the NRSV fell out of favor with Evangelicals. Perhaps disfavor came from it's enthusiastic adoption by non-Evangelical groups and denominations that often tend to lean a bit toward the left theologically, and especially its sponsor, the National Council of Churches. Or perhaps even more likely, the boom in evangelical translations in the last few years (NLT, ESV, TNIV, etc.) simply cut into the now almost two-decade old NRSV market.

Back in the days when I was using the NRSV academically in papers, I was not using it personally that much. This was a time when the NASB remained my top choice, and I viewed it as a superior translation. But I never thought poorly of the NRSV as I often hear in some conservative circles. Granted, some of its translational decisions are not near as conservative as a NASB, ESV, or T/NIV, but I was certainly never one to label it a "liberal" Bible like I sometimes hear. Bruce Metzger was at the head of the translation committee, and he's an individual I respected very much.

Lately, with my studies, I've been doing a lot of work in second-temple period Jewish literature, including what is commonly known as the Apocrypha. Although 90% of this kind of work can be done using Accordance modules (original language texts and translations) as my working source texts, I still sometimes need a physical source in front of me. Frustrated a couple of times because I didn't have an English copy of the Apocrypha in my office (my Parallel Apocrypha is more conveniently kept at home), I decided to pick up one of the new printings of the NRSV with the Apocrypha from Harper Bibles strictly to keep at school. Below is a review of the new edition, but not so much a review of the NRSV.

From Out of Nowhere, the NRSV Makes a Comeback

Surprisingly after ongoing declining sales of the NRSV, Harper Bibles has published three new editions of the of what it is calling "Standard Bibles." All three are hardbacks, although I have to admit this is one of the best looking hardback Bibles I've ever seen. The first Standard Bible contains the regular 66 books of the Bible recognized by most Protestant denominations. A second edition, called "Standard Catholic Edition, Anglicized" (which I can't seem to find on Amazon) includes the standard set of Deuterocanonical/Apocryphal books recognized by the Cathoilic church. However, the thrid edition is the one I bought: the "Standard Bible with Apocrypha." The NRSV itself is known for having the widest reach in the Christian church for books that are recognized as canonical in some form or another. This Bible contains the widest possible selection of books recognized by the church at large. Where else can you get a contemporary translation of 3 & 4 Maccabees and Psalm 151?! Esther is translated in its entirety from both the Hebrew and Greek texts as there are some differences textually besides just the additional passages.

As I mentioned, this Bible boasts a great looking cover. The Harper Bibles page for these editions calls it "leather-like" and that's exactly right. Each Bible is two toned with a material that at first glance at least looks like a kind of leather and is soft to the touch but not padded. Stitching follows the borders of the material. There's also a ribbon marker, something that doesn't always appear in hardback Bibles.

Text is set in a large typeface, probably around 10 or 11 pt. but the website doesn't specify for certain. Although descriptions on the website boast one column text, this is primarily reserved for books that are mostly prose. Poetic books, such as the Psalms are laid out in two columns. As a fan of single-column text, I find the two-column layout in the poetic books to be a detractor. I understand why they did this as the shorter lines of poetic passages leave quite a bit of blank space and no doubt making this Bible one-column throughout would have dramatically increased the number of pages used. But what about books of the Bible that contain both poetry and prose? Well, it's a mixed bag, based, I suppose on which style is in the majority. For instance, Job which begins and ends in prose text, but is poetic in the middle is entirely in two columns. Oddly, Ecclesiastes is in single-column. Isaiah which contains both poetry and prose is in two columns, but Jeremiah is in single-column! Although this Bible is not a thinline, the pages are thin nonetheless allowing for quite a bit of bleedthrough of text from other pages. Page numbering begins fresh with each section. The Old Testament contains 1129 pages; the Apocrypha, 335; and the New Testament, 351. The concordance runs from p. 352 to p. 383 thus making the entire volume almost 1850 pages.

[This paragraph added based on comments.] Another intriguing feature of the NRSV Standard Edition is a lack of full justification for its single-column text which is a rarity in Bibles that use paragraphed text. This helps the reader because non-uniform line lengths help the eyes go down the page when reading, especially when reading aloud. Prose sections in pages that employ two columns of text still use standard full justification.

These are basic text edition without introductions or cross references, but some visual variety is arrived at through graphic symbols at the beginning of each book. Acts, for instance, begins with the symbol of a dove breathing fire, obviously representative of the coming of the Holy Spirit in the second chapter. There's also a concordance in the back, but it's too condensed in my opinion to be overly useful. There are no maps, and there's no room in the margins to include meaningful self-study notes.

These Standard Bibles are very nice hardback editions of the NRSV if you don't already have a copy. And if you don't have a complete copy of the Apocryphal books, the Standard Edition with Apocrypha is the most "complete" collection you can get. Historically, it was common for Protestant Bibles to contain a section for the Apocryphal books, often in a section between the Testaments as this Bible does. This was common practice among Bible printings up until about the end of the 19th century. Luther maintained that while he didn't consider these extra books to be canon, they were good for purposes of edification. Further, I feel one of their greatest contributions is for bridging the 400 year gap between the testaments, both historically and theologically. It's near impossible to fully understand the cultural and political context of Jesus' day without the Apocrypha as well.

NASB vs. NRSV Round 5: Epistles & Revelation

This is the final round of comparisons between the NASB and the NRSV. The fourth round was posted over a month ago, and the info below has been sitting around in the comments of a much earlier post for a while now. You'll remember that this started after I made comments about the literalness of the NASB. This Lamp reader, Larry, challenged that assertion in favor of the NRSV, one of the translations he favors. This extended series of comparisons examined 50 verses from throughout the Bible, randomly selected. Although the NASB took an early lead (as I predicted), I should remind readers that literalness does not equal accuracy. Every verse/chapter/pericope must be evaluated separately. Regardless, here is the fifth round and final results of this series.

| Reference | Rick's Evaluation | Larry's Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

Rom 10:21 |

The versions are very similar and functionally the same in these verses. I give the NASB a slight edge because ten is translated in the NASB in the phrase “all the day long” as opposed to the NRSV’s “all day long.” Also I believe “stretched out” is a better rendering of exepetasa than “held out.” | This is a fascinating verse to consider, because it is one of many verses that quote the Septuagint. To the credit of both the NASB95 and NRSV, they have translated the Hebrew independently of the Greek (although the NRSV is the superior translation of Is 65:2).

Now this passage presents a particular problem because it does not even correctly quote the Septuagint we now have. Thus, the footnote in the NASB95 is rather misleading, and because of this reason, I call this for the NRSV. |

1 Cor 3:10 |

At first I was surprised that the NRSV would use “skillful” over the NASB’s “wise” for sophos. But in looking at the BDAG, the first definition for the word is “pert. to knowing how to do someth. in a skillful manner, clever, skillful, experienced.” The second meaning is “pert. to understanding that results in wise attitudes and conduct, wise.” Thus either rendering is correct based on how the translators determined context. At this writing, I’m not sure which rendering I favor. “Wise” is certainly more traditional and also found in the KJV, but that doesn’t mean it’s more correct than “skillful.” The last sentence in this verse is interesting because at first glance, one might suppose that the NRSV’s each builder is an attempt to use inclusive language over the NASB’s each man. But that is not the case. The actual word in the Greek is hekastos which is more correctly translated “each person.” Knowing that the 1995 update of the NASB cleaned up some of the masculine oriented language in these types of verses, I’m surprised to see the NASB’s rendering. There is not a separate word for “man” in this verse, just as there is no separate word for the NRSV’s “builder.” Yet the NASB introduces masculine specificity where it is not represented in the text. The KJV uses “another” and even the ESV renders the word “someone else” (as does the NIV). Based on this, I’m giving the verse to the NRSV. | I agree with Rick. NRSV. |

2 Cor 3:4 |

Neither verse translate de. I don’t really fault the NRSV for inserting “is” although the lack of it in the NASB brings that version closer to word for word literalness. The use of “that” by the NRSV is totally unnecessary. When I teach writing classes, I tell my students that if they can eliminate the word “that” in a sentence and it still makes sense to do so. This verse goes to the NASB. | I don't understand Rick's analysis here. The NASB95 is ambiguous in English (it could be interpreted as "confidence such as this have we ..." or "[wow], such confidence!" ) while the NRSV refers clearly to the pepoithesin just expressed, namely: Paul doesn't need (no stinkin' badges) any credentials other than testimony expressed by the existence of the Corinthian church. Certainly, a translation cannot be regarded as literal if it has a meaning different than the original or unnecessarily introduces an ambiguity. I call this for the NRSV. |

Col 2:13 |

The NRSV includes the kai which the NASB removes for readability purposes. But the NRSV inserts “God” where it does not actually appear in the text. This is offset by the translational note, however. Although this is contextually correct, it does not accurately reflect the text. I don’t personally have a preference for “transgressions” vs. “trespasses” for paraptoma. I’m calling this one a tie. | Since our ground rules were to count textual notes in our analysis, I can't count the extra "God" against the NRSV. For the reasons observed by Rick, I thus weigh the factors towards the NRSV. |

Col 3:13 |

The NASB does a better job of keeping the particples in place, which the NRSV has altered to become simple imperatives. "bearing" in the NASB captures the participle anechomenoi much better than "Bear" in the NRSV just the same as "forgiving" is a closer equivalent to charizomenoi than "forgive."

The NASB fails to capture the conditional ean which the NRSV does represent with "if." However, the last phrase in the original, houtos kai humeis is literally represented in the NASB's "so also should you" as opposed to the NRSV's "so you also must forgive." Thus, overwhelmingly, this verse goes to the NASB. |

I agree, the NASB95 is more literal here. |

1 Tim 6:6 |

This verse is part of the same sentence as the previous verse (following NA27). The NRSV translators chose to create a break and make a new sentence as opposed to the NASB which follows the structure set in the NA27.

Should I even point out that the NRSV begins the verse using a pronoun that lacks an antecedent? The phrase oudeis anthropon would literally be "no one of humans." Neither version chooses to translate this phrase literally. The NASB chooses "no man" while the NRSV chooses "no one," each opting to ignore half the phrase. Of course, neither translation can be faulted as an actual literal translation would prove awkward in English. All that to say, I'm calling this verse a tie (in spite of the NRSV's questionable grammar). The NASB follows the sentence structure better, but the NRSV includes the conditional. |

I'm not sure I understand your point about the NRSV's "he" lacking an antecedent -- certainly it is present in the preceding verses. However, I'll go along with your calling it a tie. |

Clarification: |

I was referring to the NRSV's starting the sentence with it, a pronoun, actually referring to the he that comes after it--which by defintion can hardly be an antecedent to the pronoun. This is hardly good prose, but it didn't affect my scoring for that verse. | That's not ungrammatical, just awkward -- the "it" matches with the "who" clause. The NASB95 uses this sentence structure in its translation of Daniel 2:21, for example.

However, the NRSV is not very faithful here to the Greek. |

Heb 10:9 |

There's not much to functionally distinguish between the versions in this verse. However, based on the theological context of the larger passage, I like the NRSV's use of "abolishes" for anairei than the NASB's "takes away."

So, I give this verse to the NRSV. |

I disagree, and call this for the NASB95 -- largely because of the footnote which more accurately reflects the tense. |

Heb 10:19 |

I have never liked the NRSV's use of "friends" for adelphoi. In my opinion "friends" loses the familial aspect of the word in Greek. I don't know why the translators did this sometimes because in other places such as Rom 1:13, "brothers and sisters" is used which is a perfectly valid translation.

I don't think "holy place" vs. "sanctuary" is an issue for hagion since both mean the same thing. Literally the verse reads "the entrance into the holies," but neither version translates it this way. Tie. |

I also count this as a tie -- "sanctuary" is closer to the Greek, but so is brethren. |

James 2:8 |

I'm giving this to the NASB for the following reasons: (1) the NASB follows the word order more closely than the NRSV, (2) the NASB translates Ei mentoi whereas the NRSV does not, and (3) the NASB provides an alternate translation and the NRSV does not. | I agree, this goes to the NASB95. |

James 2:9 |

Umm... tie. | This is very close -- the difference is between "commit" and "are committing". Normally, I would say that "are committing" is closer, but the later translation of "are convicted" rather than "are in the state of conviction" (which doesn't sound very good in English) presents a problem. Both egarzesthe and elenchomenoi are present tense in the Greek, but I am not sure how to translate this into English using only present tense verbs. The Vulgate captures this with si autem personas accipitis, peccatum operamini, redarguti a lege quasi transgressores but in English something has to give. Given that, I think the NASB95 and NRSV are both approximately close, so I agree this is a tie. |

Final Comments: |