YANIVB

“Of making many NIV Bibles there seems to be no end, and a lack of TNIV Bibles wearies my soul.”

(With apologies to Qoheleth and Ecclesiastes 12:12)

I took an online survey from Zondervan tonight for a YANIVB. What’s a YANIVB? Well, YANIVB stands for “Yet Another NIV Bible.” While the TNIV seems to be losing ground everyday, it seems that there’s no end in sight for new NIV Bibles.

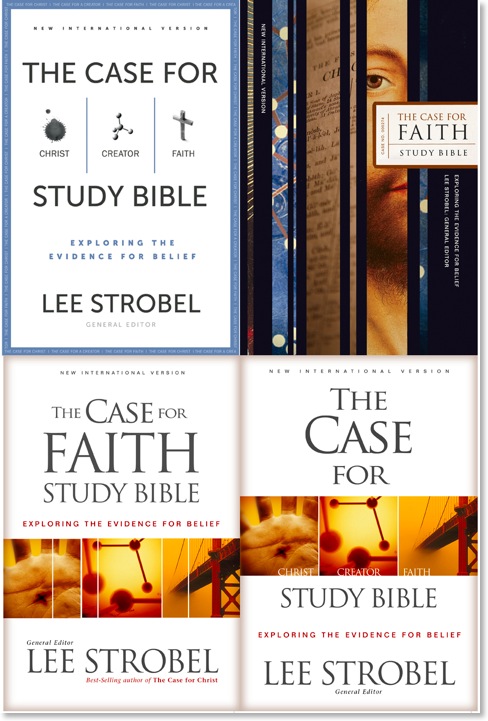

The Bible in question here? Well, it’s based upon the work of Lee Strobel and called The Case for Faith Study Bible. It’s so early in development stage that if you run a Google search on this Bible right now--even if you put quotation marks around it--you won’t get any hits. At least if you run your search within a close timeframe for my writing this post.

The main thrust of the survey was to select which cover I liked best:

Incidentally, I liked the top right cover best and the bottom left cover second best.

Of course, as you would guess, I’ve got a HUGE problem with this Bible. No, it’s not the theme. For what it’s worth, I think Lee Strobel is a great guy, and I’ve given away some of his books. My problem with this Bible is that it’s a NEW Bible released with the NIV as its text rather than the TNIV.

I really don’t understand this. The NIV continues to cannibalize sales of the TNIV and lessen the latter’s chance of acceptance. It is clearly shortsighted for Zondervan to keep the NIV as its flagship translation to the neglect of the TNIV, to continue to promote NEW products based around the NIV while new TNIV projects are few and far between. One day the NIV will slip from its spot as bestselling translation, but it won’t be the TNIV to take its place because the TNIV will have died from neglect by that time.

But do you want to know what makes creating Lee Strobel’s Bible around the NIV most egregious?

Well, if you go over to TNIV.com, click on the “Who’s Reading It” tab, and then click on the “Who Recommends It” tab, guess who appears FIRST!

Thats right! There’s Lee Strobel, front and center, stating “I’m thankful to have the TNIV as one more valuable tool in reaching the next generation.”

Well, too bad, Mr. Strobel, we’re going to make you use the Bible of the last generation: the NIV!

I’ve said over and over that Zondervan needs to put strong testimonial power behind the TNIV for people to consider it. Lee Strobel and The Case for Faith Study Bible would be a perfect match for the TNIV. And yet, before it ever even sees print, it becomes another wasted opportunity for Zondervan to move its resources behind the TNIV. YANIVB is what it becomes. When will the tide turn?

Of course, for all of Lee Strobel’s wish for the TNIV to become a valuable tool in reaching the next generation, and for all of Zondervan’s original marketing of the TNIV as a Bible for the 18 to 34 crowd, can anyone tell me why The Student Bible has been revised since the release of the TNIV, and yet still remains an NIV Bible?

Here’s a new slogan: “TNIV: The Best Bible No One Ever Read.”

HT: Jay Davis

![]()

Craig Blomberg Clarifies His Position on the NLT

I relished the chance to work on the NLT (New Living Translation) team to convert the LBP into a truly dynamic-equivalent translation, but I never recommend it to anyone except to supplement the reading of a more literal translation to generate freshness and new insights, unless they are kids or very poor adult readers. My sixteen- and twelve-year old daughters have been weaned on the NLT and have loved it, but both already on their own are now frequently turning to the NIV.

The original source for this statement is actually a review by Blomberg of Leland Ryken’s book, The Word of God in English: Criteria for Excellence in Bible Translation. The review can be found in the July, 2003, issue of the Denver Journal.

The statement quoted above is used by Michael Marlowe in his fairly critical review of the NLT. In fact, Marlowe gives the context for Blomberg’s quote as “responding to criticism of the NLT.” In Marlowe’s review of the NLT, he makes this statement before supplying the quote by Blomberg above:

Finally, we note that Craig L. Blomberg of Denver Seminary, who was the principal translator for the NLT's Gospel according to Matthew, has explicitly stated that this version is not suitable as a regular Bible for adults. Responding to criticism of the NLT, Blomberg explained that the version is for "kids or very poor adult readers," and he suggested that readers of the NLT should move on to a more accurate version when they are able:

But the context that Marlowe gives is completely wrong. Blomberg isn’t responding to criticism of the NLT at all; rather, he’s writing a review of Ryken’s book! And did Blomberg explicitly say that the NLT “is not suitable as a regular Bible for adults”? Well, not precisely. At the very least Marlowe seems to be overreaching a bit, and seems to be looking for support for the fact that he does not like the NLT. Incidentally, both Marlowe’s statement and Blomberg’s quote are repeated verbatim at the Theopedia’s article on the New Living Translation.

Considering that Blomberg’s review dated back to 2003, I was curious to know if he still held the same feelings about the NLT. Does he really only recommend it to kids or adults who are very poor readers? His statement was made a year before the NLT second edition was released, which I believe fixed a lot of problems in the first edition as well as creating a translation which is sometimes more literal and even more traditional in places than the first edition.

Dr. Blomberg and I have now exchanged a handful of emails on this subject and he has given me permission to share the content of those emails on the internet.

In general, Dr. Blomberg told me that does not recommend the NLT as a primary Bible for adults, but he does recommend it as a supplement to reading other Bibles. However, in another email he offered three contexts for choosing the NLT. I have broken up his statement and added numbers to delineate his three options more clearly:

- I very much approve of it for people who want a second (third, fourth, or whatever) take on the text,

- or who want to hear it in a fresh way,

- or who simply for whatever reason want a dynamically equivalent rather than a formally equivalent (or hybrid) translation.

Dr. Blomberg said that the evaluation immediately above is one he held to

I will send Dr. Blomberg a link to this post. If you would like to leave your thoughts in the comments, perhaps he may take the opportunity to respond if he has time.

Also, I highly recommend for your reading Dr. Blomberg’s post last year on the Koinonia Blog: “Demystifying Bible Translation and Where Our Culture Is with Inclusive Language.”

*This paragraph was added after the initial posting of this blog entry.

Loose Loins Sink Kings (Isaiah 45:1)

I’ve read through the book of Isaiah quite a few times, but I’ve discovered over the years that when I prepare to teach a passage, I always find new elements of the text I hadn’t seen before. One of these insights came from a phrase I came across in Isaiah 45:1, which is part of Isaiah’s prophecy to Cyrus.

In the Hebrew, the phrase is simply וּמָתְנֵי מְלָכִים אֲפַתֵּחַ which translates somewhat literally as “and loins of kings I will loosen/open.”

The context revolves around Cyrus of Persia, the king who would allow the Israelites to return to their homeland and rebuild Jerusalem and the Temple as chronicled in 2 Chronicles 36 and Ezra. Cyrus is an interesting individual. He was a pagan king, comparable to Nebuchadnezzar who, in spite of his foreign religion, was called God’s servant (Jer 25:9; 27:6; 43:10). Like Nebuchadnezzar, God chose to work through this non-Israelite as part of his divine purposes, demonstrating his sovereignty even upon those who do not acknowledge him.

There are allusions to David in God’s depiction of Cyrus. He calls him “my shepherd” (רֹעִי) in Isa 44:28 and perhaps more startlingly his “anointed one” (מָשִׁיחַ, /māšiyaḥ). Thus Cyrus is the only individual in the Bible to be called “anointed one” (or messiah) outside of Israelite kings, priests and Jesus Christ. Cyrus had also been raised by a shepherd. Further, there seems to be imagery related to Moses as well as Cyrus becomes the one who leads (by decree) God’s people out of their captivity to the Promised Land.

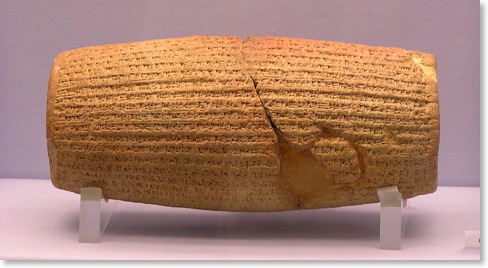

Above: The Cyrus Cylinder which includes detail of the king’s granting expatiates permission to return to their homelands.

Source: Bible Lands Photo Guide, version 3 (Accordance)

I try very hard when I’m preparing a lesson to attempt interpretation by myself first before consulting commentaries. I had to admit (although it seems somewhat obvious now) that I was stumped by this reference to God loosening the loins of Cyrus’ rival kings. I’ve begun teaching from the New Living Translation on Sundays, and I consulted Isa 45:1 in the NLT:

This is what the LORD says to Cyrus, his anointed one,

whose right hand he will empower.

Before him, mighty kings will be paralyzed with fear.

Their fortress gates will be opened,

never to shut again.

Most formal translations simply translate the phrase literally, “loose the loins of kings” or something similar. The NLT certainly gets the end result across. I understood that. None of the kings who went before Cyrus would be able to stand before him. But what did the phrase actually mean? I wondered if it meant that foreign kings would be impotent before Cyrus, or perhaps it meant they would wet themselves. The problem, as I would later discover, was that my focus was too literally loin-centered.

Incidentally, when I taught the lesson Sunday and was relaying Cyrus’ rather colorful history, one person in the class asked whether Cyrus came “before or after ‘that guy’ in 300.” I told him that Cyrus came before Xerxes who was featured (rather outlandishly) in the movie 300. But I pointed out that the incredibly large army depicted in that movie had not been built by Xerxes (for the most part), but rather by Cyrus much earlier before him.

Using Accordance, I tried running searches for the exact phrase and then similar phrases, but to my knowledge (feel free to correct me if I’m wrong), there are no other occurrences of loins being loosened, only tightened up, or more appropriately girded up. And then suddenly it made sense! My problem was that I had not been thinking in terms of Hebrew and ANE culture.

At this point, thinking I’d figured it out, I went ahead and consulted a number of commentaries that confirmed my hunch. In the Bible, to “gird up one’s loins” (see Exod 12:11; 1 Kgs 18:46; 20:32; 2 Kgs 1:8; 4:29; 9:1; Job 12:18; 38:3; 40:7; Jer 1:17, esp. in more formal translations) was to tuck the ends of one’s garments into one’s belt so as to be ready for any kind of action, whether fight or flight. What was being described in Isa 45:1 was just the opposite.

Thus, before Cyrus, God would immobilize any king or king’s army who would oppose him. Their readiness for battle would come to nothing. The TNIV renders the phrase “strip kings of their armor” which nicely captures the military aspects just as the NLT’s rendering above relates the psychological end result. The ESV translates the phrase as “to loose the belts of kings,” but that sounds a bit too much like the aftereffects of a Thanksgiving meal.

Regardless, it’s clear in the passage that the God of the Bible is sovereign, choosing to use whom he will when he will, often despite the objections of those who feel themselves to be part of the “in group” (Isa 45:9-13). To those who first objected, God had this message:

“I will raise up Cyrus to fulfill my righteous purpose,

and I will guide his actions.

He will restore my city and free my captive people—

without seeking a reward!

I, the LORD of Heaven’s Armies, have spoken!”” (Isa 45:13, NLT)

And as history records, that’s exactly what happened.

The Shack: A Review (sorry I couldn't think of a more clever title, but all the good ones have already been used)

One day Abraham was sitting at the entrance to his tent during the hottest part of the day. He looked up and noticed three men standing nearby. When he saw them, he ran to meet them and welcomed them, bowing low to the ground.

“My lord,” he said, “if it pleases you, stop here for a while. Rest in the shade of this tree while water is brought to wash your feet. And since you’ve honored your servant with this visit, let me prepare some food to refresh you before you continue on your journey.” “All right,” they said. “Do as you have said.”

Then a few verses later (13), in the story, the reader learns unexpectedly that one of the three visitors is God when reading “Then the LORD said to Abraham.” The all-caps designation stands in place of the divine name for God, (יהוה / Yahweh), leaving no doubt to the reader that one of the strangers is God, the same God who will appear to Moses in Exodus 3.

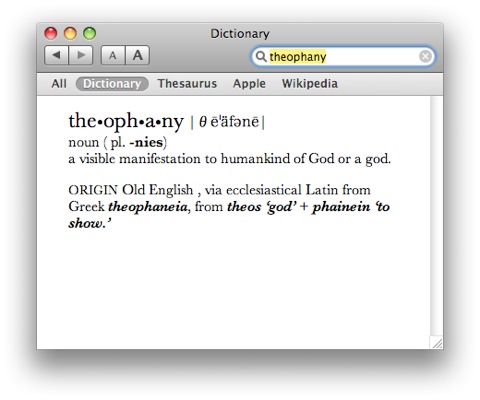

Ever since the early Christians began to work out the relationship of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in what would come to be known as the Trinity, many Christian writers, teachers, and preachers over the last two millennia have looked at Genesis 18 and have suggested that the three individuals who visited Abraham and his family at the Oaks of Mamre were, in fact, the three persons of the Trinity in physical manifestations. This is what is known in theological terms as a theophany, a physical manifestation of God for the purpose of relating to human beings.

The problem is that the Genesis text never specifically states the identity of the two other than beyond the one of them already identified as Yahweh. While some would like to equate Yahweh with God the Father exclusively, traditional Christian doctrine doesn’t make this claim either. In fact, from a Christian perspective, Yahweh is not limited to one person of the Trinity. See for example John 8:58, where Jesus essentially tells the Jewish leaders that they are in the presence of the same “person” who appeared to Moses at the burning bush in Exodus 3, but that doesn’t imply that the Father and Holy Spirit weren’t there, too.

The passage with Abraham in Genesis 18 is subtle. When encountering it for the first time, the reader/hearer may not expect initially that God is one of the visitors, although it is foreshadowed at the beginning of v. 1. Whether the other men who were present with Abraham were theophanies of the other persons of the Trinity or whether they were angels or even someone else, we simply don’t know because we weren’t privy to the entire conversation. And that’s the way the Bible generally works--less is more, if you will.

That’s a very brief synopsis of the book, and my hunch is--since I’m so late to the game with this review--that most readers of This Lamp know all this anyway. I’m writing this review because I’ve received questions and emails since last Fall asking what I think of The Shack. By simply being able to point people to this page, I won’t have to repeat myself so much.

Kathy and I listened to the unabridged audio version of The Shack in December while we were traveling to Louisiana and back for Christmas. I don’t own a physical copy of the book, so I won’t be able to quote it verbatim, but it doesn’t really matter. I can still offer my general impression and point readers to other sources.

You need to know, up front, that I don’t think very highly of The Shack on multiple levels. I am certain that some of you will think I’m just being theologically picky, that I’ve let formal study of the Bible make me into some kind of doctrinal do gooder who can’t allow my imagination to see God in creative ways. If you think that, you simply don’t know me well. But don’t just ask me about this book, ask my wife Kathy. She may be less charitable than me.

But let me start by being charitable. Let me start by saying that William P. Young seems to be a really great fellow. At the end of our audio version of The Shack we were able to listen to an extended interview with Young. His motives seem to be nothing more than sincere. At the very least, he is certainly the benefactor of fortunate circumstances with the sale of The Shack into the millions of copies at this point, and no doubt many of the publishers who turned him down greatly regret doing so.

Furthermore, I don’t think that Young was attempting to be unbiblical, let alone introduce heresy into his novel. Nevertheless, he did.

So much has been written about the doctrinal error in The Shack, I started not to even comment on it. One can easily run a Google search for “The Shack” and “heresy” and find a multitude of pages, so I doubt I could top what has already been done. However, let me reproduce here three of Norman Geisler’s fourteen errors in The Shack. Geisler may not win an award for best webpage layout, but he offers a strong theological critique for Young’s work.

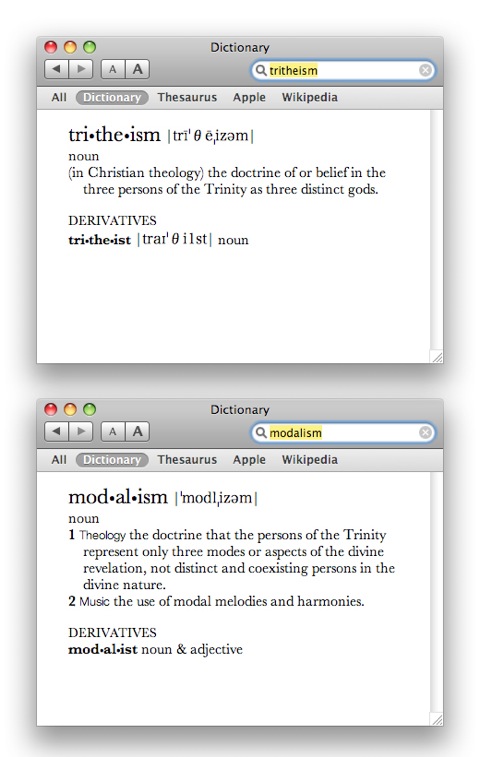

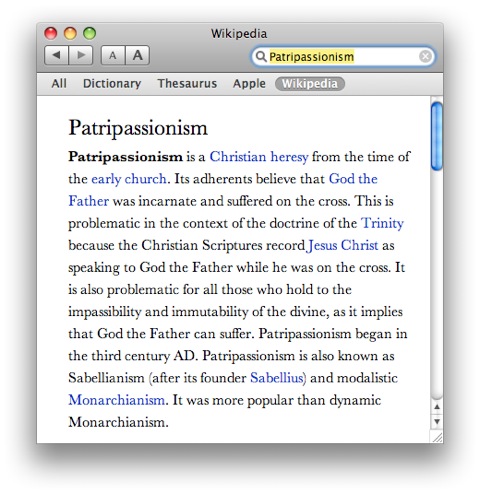

In addition to an errant view of Scripture, The Shack has an unorthodox view of the Trinity. God appears as three separate persons (in three separate bodies) which seems to support Tritheism in spite of the fact that the author denies Tritheism (“We are not three gods” ) and Modalism (“We are not talking about One God with three attitudes”—p. 100). Nonetheless, Young departs from the essential nature of God for a social relationship among the members of the Trinity. He wrongly stresses the plurality of God as three separate persons: God the Father appears as an “African American woman” (80); Jesus appears as a Middle Eastern worker (82). The Holy Spirit is represented as “a small, distinctively Asian woman” (82). And according to Young, the unity of God is not in one essence (nature), as the orthodox view holds. Rather, it is a social union of three separate persons. Besides the false teaching that God the Father and the Holy Spirit have physical bodies (since “God is spirit”—Jn. 4:24), the members of the Trinity are not separate persons (as The Shack portrays them); they are only distinct persons in one divine nature. Just as a triangle has three distinct corners, yet is one triangle. It is not three separate corners (for then it would not be a triangle if the corners were separated from it), Even so, God is one in essence but has three distinct (but inseparable) Persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Problem Five: An Unbiblical View of Punishing Sin

Another claim is that God does not need to punish sin. He states, “At that, Papa stopped her preparations and turned toward Mack. He could see a deep sadness in her eyes. ‘I am not who you think I am, Mackenzie. I don’t need to punish people for sin. Sin is its own punishment, devouring you from the inside. It is not my purpose to punish it; it’s my joy to cure it’” (119). As welcoming as this message may be, it at best reveals a dangerously imbalanced understanding of God. For in addition to being loving and kind, God is also holy and just. Indeed, because He is just He must punish sin. The Bible explicitly says that” the soul that sins shall die” (Eze. 18:2). “I am holy, says the Lord” (Lev. 11:44). He is so holy that Habakkuk says of God, “You…are of purer eyes than to see evil and cannot look at wrong…” (Hab. 1:13). Romans 6:23 declares: “The wages of sin is death….” And Paul added, “‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay’ says the Lord” (Rom. 12:19).

In short, The Shack presents lop-sided view of God as love but not justice. This view of a God who will not punish sin undermines the central message of Christianity—that Christ died for our sins (1 Cor. 15:1f.) and rose from the dead. Indeed, some emergent Church leaders have given a more frontal and near blasphemous attack on the sacrificial atonement of Christ, calling it a “form of cosmic child abuse—a vengeful father, punishing his son for offences he has not even committed” (Steve Chalke, The Lost Message of Jesus, 184). Such is the end of the logic that denies an awesomely holy God who cannot tolerate sin was satisfied (propitiated) on behalf of our sin (1 Jn. 2:1). For Christ paid the penalty for us, “being made sin for us that we might be made the righteousness of God through him” (2 Cor. 5:21), “suffering the just for the unjust that He might bring us to God” (1 Pet. 3:18).

Problem Six: A False View of the Incarnation

Another area of concern is a false view of the person and work of Christ. The book states, “When we three spoke ourself into human existence as the Son of God, we became fully human. We also chose to embrace all the limitations that this entailed. Even though we have always been present in this universe, we now became flesh and blood” (98). However, this is a serious misunderstanding of the Incarnation of Christ. The whole Trinity was not incarnated. Only the Son was (Jn. 1:14), and in His case deity did not become humanity but the Second Person of the Godhead assumed a human nature in addition to His divine nature. Neither the Father nor Holy Spirit (who are pure spirit--John 4:24) became human, only the Son did.

On a completely different level, The Shack doesn’t work for me simply because overall, it’s not good literature. Let me qualify that statement. I’ll admit up front that everything leading up to Mack’s entering the shack where his dialogue with God begins kept my keen attention. It was a tragic story about the loss of his daughter and his estrangement from God, and one that I was really interested in. And I would also point to Mack’s vision (or whatever you want to call it) in which he was reconciled to his earthly father--powerful stuff.

Unfortunately, it’s the most significant part of the book--his encounter and dialogue with the persons of the Godhead--which not only are full of bad theology, but really are the weakest narrative parts of the whole story. The dialogue is overblown, repetitive, and pretentious. If you want good theological dialogue, I recommend Peter Kreeft (see here

and here

Besides that, there is too much content in the story that’s just plain weird or cheesy. The ongoing joke about Mack’s potential flatulence causing Papa (God the Father, as you’ll remember) to refuse him any more greens at dinner was more weird than humorous to both Kathy and me. Papa laughing at Jesus and calling him “Butterfingers” when he let slip a casserole dish, letting it come crashing to the floor seemed not only odd, but also introduced another doctrinal error. Essentially Young has Jesus err, something the Bible says he was incapable of doing. Would this also mean that Jesus occasionally smashed his thumb during carpentry work in Nazareth? Such a thought or question might not even matter to most reading this, but the implications start to get unsettling.

I had to grimace and shake my head when Mack opened his nightstand drawer in his bedroom at the shack and found a Gideon’s Bible. Ha ha ha. To me, that’s the kind of “gimmick” that distracts more than adds to the story. Further, when Jesus and Mack needed to walk to the other side of the lake, I knew it was coming before Young said it--sure enough, they would walk across the water! What else would you do if you were with Jesus? It’s these kind of gee whiz moments that I felt were bordering on immature and simply not needed in the story.

And should I even go into how Mack’s conversations with Papa in the kitchen while she was cooking was a blatant rip-off of Neo in The Matrix conversing with the Oracle in her kitchen while she made cookies? Should I question how Mack’s character, who was supposedly seminary trained, could ask the most inane questions of God, that any student who went to an institution worth its salt, or for that matter, any laymen who’d spent any decent amount of time with the Bible should know?

What boggles my mind is that a number of well-respected individuals do consider The Shack to be good literature. One endorsement comes from Eugene Peterson, an individual I admire very much and happen to be reading currently. Of The Shack, Peterson says this:

When the imagination of a writer and the passion of a theologian cross-fertilize the result is a novel on the order of The Shack. This book has the potential to do for our generation what John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress did for his. It's that good!

The Shack equated to Pilgrim’s Progress? Really? Seriously? I read that and it makes me wonder if Peterson actually read the book. I don’t mean that as an insult against him. Regularly, well known individuals are approached by publishers, given a synopsis of a book, and then an already written endorsement for the individual to sign. Most of the endorsements you see on the back covers of books are handled this way. Endorsements should be evaluated with more than a grain of salt.

Yet, I could see why someone like Peterson would appreciate the concept of The Shack simply because of the way he sees the communal nature of the Trinity. In Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places

Trinity understands God as three-personed: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, God in community, each “person” in active communion with others. We are given an understanding of God that is most emphatically personal and interpersonal. God is nothing if not personal. If God is revealed as personal, the only way that God can be known is in personal response. We need to know this. It is the easiest thing in the world to use words as a kind of abstract truth or principle, to deal with the gospel as information. Trinity prevents us from doing this.

The premise of The Shack promises what Peterson describes above; unfortunately it does not satisfyingly deliver. And that’s the key question--does The Shack really satisfy? Ask yourself that if you really liked the book. Strip away the way the persons of the Godhead were presented in very likable portrayals. Strip away the meal time conversations, the walking on water across the lake, and ask yourself if you really know God better.

Here’s the problem: ultimately we are not given real answers by God in The Shack. Rather we are given answers as best as William P. Young understands God and can speak for God. See, in any work of fiction, the writer is ultimately God. The writer sets the events in an absolute predetermined way, and all characters--even God himself as a character--will speak and behave only in how the true god of the story (the writer) thinks they should. I’m not trying to be harsh here, but I’m trying to remind readers of this very important fact: The Shack does not contain a message from God; it contains a message about God from the writer--a writer whom to my knowledge hasn’t received any more revelation from the real God than you or me. This writer did the best job he knew how, but ultimately, he doesn’t really give us anything new and certainly nothing revelatory about God and our relationship to him.

And frankly, it saddens me that so many have so uncritically embraced the book. You don’t have to be a theologian to see problems in The Shack. Kathy does not consider herself a theologian at all, but as we were listening to the audio version, she offered a blow by blow commentary of its weaknesses as we listened. The book right now has almost 3000 reviews on Amazon.com. One reviewer, who said he liked the book, but gave it only three out of five stars noted that he was very concerned by the “book being embraced with nothing but naive, uncritical, and untempered enthusiasm.” This concerns me as well.

My friend Todd Benkert has written about the popularity of The Shack, trying to figure out why it’s been so very popular for a self-published book. In his blog post, “One More Post about The Shack with ‘Something Else’ to Consider,” Todd offers this theory:

The Shack offers people what the church, by and large, does not--hope for and acceptance of messed up people.

Mack is a messed up person. He has real hurts. He has experienced real pain. He does not act and think the way a Christian ought to act and think. In fact, he questions and even blames God for what has happened to him. People relate to Mack. They relate to the pain and hurt and struggle and questions Mack has. And they find from Papa, Jesus, and Sarayu the kind of understanding and acceptance that is, for whatever reason, missing in the church.

Todd may very well be on to something. My concern is that while the Church does indeed need to get its act together in regard to people who are hurting, The Shack is not really a solution. It’s a band aid for a much more serious kind of wound. Think about this really-- if you knew someone who had lost a child through murder or some other tragic means, would you really consider giving The Shack to a hurting person to read? I cannot fathom that idea.

And I know that many people who’ve appreciated The Shack feel as if they can relate to God better after reading the book. But if someone wants to know what God is like, rather than handing them a copy of The Shack, (and pardon me if this sounds unnecessarily church) I’d give them a copy of the New Testament. In the Gospels, we learn how God “became human and made his home among us.” In doing so, not only did he provide a way for us to be reconciled to him, he also “put on a face” in the person of Jesus. You want to know what God is like? Read the Gospels. Do you want to know specifically what the Father and Son are like and how they interrelate? Engage in a good study of Jesus’ parables. If you’re curious to know how to relate to the Holy Spirit, read the Book of Acts. God has revealed himself already through his Son and through his written Word. If you still cannot relate, it may be your translation of the Bible. Be sure you are reading something translated in the last decade or so in normal, contemporary English.

I have no trouble recommending the New Testament as a way of relating to God. That’s one of its major functions. But sadly, I cannot recommend The Shack under any circumstances or in any contexts.

For Further Reading:

• “The Shack: Helpful or Heretical? A Critical Review by Norman Geisler and Bill Roach”

Geisler and Roach outline 14 primary theological blunders made in The Shack. Some of these are more significant than others, but they still make a compelling case.

• “A Look at The Shack” (The Albert Mohler Radio Program)

You can download this MP3 file and listen to it on your iPod or iPhone while driving to work.

Lest anyone accuse me of not giving equal time, here are two reviews a little more positive worth considering:

• “Reading in Good Faith” by Derek Keefe

Acknowledging there are problems in the book, Derek Keefe finds some value in The Shack that the church can benefit from.

• “The Shack by King David” by Gordon MacDonald

MacDonald wonders if anyone took offense when David portrayed God as a smelly, dirty shepherd in Psalm 23.

The NLT and the Language of Atonement

Todd Benkert is a pastor in Indiana and a friend of mine I’ve known for quite a while. Over the years, we’ve had a number of discussions including ones about what what translations are beneficial for teaching and preaching. As I’ve been contemplating making the NLT my primary public use Bible in the church (I’ve already been using it with college classes that I teach), Todd has been thinking about using the NLT from the pulpit. Currently, he uses the ESV, but he recognizes its deficiencies.

In a recent post on Todd’s website Be My Witnesses, we got into a discussion about whether or not the NLT would work in certain public settings. In the comments, Todd wrote the following:

My main qualm, which I can't decide if its a strength or weakness of the NLT, is that is removes justification terminology from the text (see, e.g., Rom 3). On the one hand, it is helpful because the concept is now accessible to the reader. On the other hand, the systematic theologian in me want to retain the word and then explain it. If I can get over that, then I'm all in with the NLT.

Todd gave me permission to reproduce my reply here which I’ve cleaned up a little bit and reproduced below:

Let's take for instance Romans 3:25, which in the ESV reads:

whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood, to be received by faith. This was to show God’s righteousness, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over former sins.

Now, I chose the above verse because it is from Rom 3, which you referred to as a chapter in the NLT which "removes justification terminology from the text." I also made bold propitiation because it is certainly a prime example of "justification terminology."

Propitiation is one of those heavily loaded theological words which carries a lot of meaning in a very small label. Now, as you know fully well, the underlying Greek word is ἱλαστήριον. When a word like propitiation is used in a verse like this, really it acts more as a placeholder for the larger context. In other words, the average person in the pew--in your pew--is probably not going to walk around with a fully developed theology of propitiation in his or her head. Some will, but realistically, most won't.

What this means is that regardless of what word is used here, whether it is propitiation orhg the phrase "sacrifice of atonement" (NIV, NRSV), it will still require some amount of explanation by you. Incidentally, the word atonement was coined by Tyndale for use in his OT translation because he couldn't find a suitable English word for כָּפַר.

The question remains whether it is better to have that theologically loaded word (really just a label, a placeholder) propitiation in the text or is something else just as suitable or even better?

I've seen people evaluate translations of the Bible (and I think I used to do it myself) based on whether the word propitiation was used or not in the New Testament, specifically in Rom 3:25; Heb 2:17; 1 John 2:2; and 4:10 (although technically, the last two references use ἱλασμός in the Greek).

What's interesting is that although the word propitiation was used in the King James Version, it was not used in William Tyndale's translation upon which the KJV was primarily based.

The Tyndale NT reads this way (with emphasis added) in Rom 3:25

whom God hath made a seate of mercy thorow faith in his bloud to shewe ye rightewesnes which before him is of valoure in yt he forgeveth ye synnes yt are passed which God dyd suffre

So where did the KJV translators get the word propitiation from? Why, straight out of the Latin Vulgate! Here is Rom 3:25 in Latin:

quem proposuit Deus propitiationem per fidem in sanguine ipsius ad ostensionem iustitiae suae propter remissionem praecedentium delictorum

What is inescapable, regardless of how one looks at it, is the KJV translators, rather than trying to actually translate ἱλαστήριον into an English equivalent, instead "cheated" and just grabbed the Latin word (this, of course, is not much different than what was done by simply transliterating βαπτίζω as baptize, rather than correctly translating it as "immerse," but now the real "Baptist" [pun intended] is coming out in me).

So, what does ἱλαστήριον actually mean (I know you know what it means, but bear with me for sake of discussion)? Or what is it that Jesus actually did for us on the cross (the real question)? I'm not going to try to answer the second question just yet, but I will say that when NT writers, especially in the epistles, try to answer that question, their answer at the most basic level is some kind of common analogy for what took place on a spiritual level. This is true, regardless of whether Paul is speaking of ἱλαστήριον in Rom 3:25 or ἀντίλυτρον ("ransom") in 1 Tim 2:6. In the Reformation, emphasis came back upon ἱλαστήριον as a primary image (which I completely affirm), but in the early church, made up of the poor and in many cases, freed slaves, the idea of ἀντίλυτρον was favored. The reality is we need all of the images the NT provides to try to understand what Jesus did for us on the cross.

But back to my original question in regard to what ἱλαστήριον actually means-- When Paul uses this word, he is borrowing it from two arenas. On one hand, it's a pagan word used to describe the appeasement of a foreign god in their sacrificial ceremonies. The word meant this throughout ancient Greek literature, especially in regard to appeasing the wrath of the pagan God through sacrifice. On the other hand, the word ἱλαστήριον had been "co-opted" a couple of centuries earlier by the writers of the Septuagint to refer to the Old Testament mercy seat--the place above the ark of the covenant where sacrificial blood was sprinkled by the high priest to make atonement (thank you, William Tyndale) for Israel's sins; that is, to restore the people of Israel into fellowship with God.

So what did Jesus do on the cross (if I can take a stab at the second question now)? Well, to follow the lead of the NT writers and also Tyndale, he "mercy seated" us with God.

Now, back to that Latin label/placeholder propitiation... This word sees the ἱλαστήριον as the place of atonement. Jesus was the "place" where God's anger was removed. But as you probably remember, C. H. Dodd in The Bible and the Greeks rejected Jesus as the place of atonement. He saw this as too closely tied to paganism. Furthermore, he was uncomfortable with the idea of a "wrathful" God. He said expiation was a better translation because it was God’s appointed means to deal with our situation. On the Day of Atonement, he makes the effects of sin ineffective. Emphasis is on what God does (expiation), rather than what humans do (propitiation).

And of course, C. H. Dodd influenced translations of the Bible such as the RSV and NEB that opted for the word expiation in a verse like Rom 3:25 rather than propitiation.

But then Leon Morris came along, and in New Testament Studies said that wrath was indeed present in both Old and New Testaments (contrary to Dodd). Further, Morris went on to say that ἱλαστήριον is not an either/or in regard to expiation or propitiation, but a both/and: Morris said God expiates and is propitiated. The opposite of love is not wrath; the two are not incompatible. Anger is an appropriate reaction at times to those you love. The opposite of love is hatred—something into which anger can turn. Morris saw wrath as a positive angry love that does many wonderful things in the world.

In the Day of Atonement, God’s anger loomed large. Sin was taken seriously. Paul’s thought was how the Day of Atonement was understood in his time, not necessarily when it was who first proclaimed in Leviticus.

Since Morris, we have seen the rise of Bible translations that opted not to use either word (propitiation or expiation), but rather simply to translate ἱλαστήριον as "sacrifice of atonement" or something similar, leaving it up to the preacher or teacher to explain further if desired.

So back to the NLT...

The 1996 NLT reading of Rom 3:25 may have simply tried to do too much:

For God sent Jesus to take the punishment for our sins and to satisfy God’s anger against us. We are made right with God when we believe that Jesus shed his blood, sacrificing his life for us. God was being entirely fair and just when he did not punish those who sinned in former times.

There's definitely the standard "propitiatory" language in there. In fact, propitiation is defined pretty clearly in that rendering, over and above what the Greek actually says.

The 2004 revision is less overt:

For God presented Jesus as the sacrifice for sin. People are made right with God when they believe that Jesus sacrificed his life, shedding his blood. This sacrifice shows that God was being fair when he held back and did not punish those who sinned in times past

"Jesus as the sacrifice for sin" is probably closer to that non-specific "sacrifice of atonement" in the NRSV & NIV.

And for point of reference, the translators for Romans in the NLT are Gerald Borchert, Douglas Moo and Thom Schreiner -- a pretty good mix of scholarship and viewpoint.

So, finally, back to your original concern, regardless of how it's worded, I believe there's still PLENTY for you as pastor/teacher to explain. I really wouldn't let lack of formal theological language--especially those which are simply Latin loan words--hold you back.

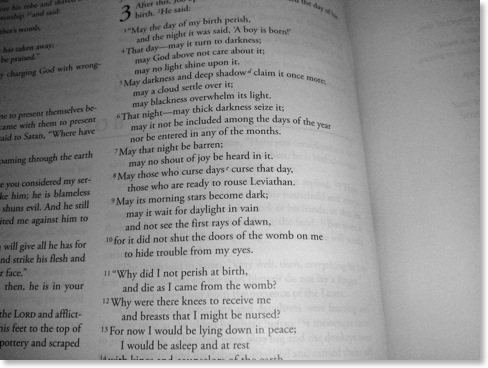

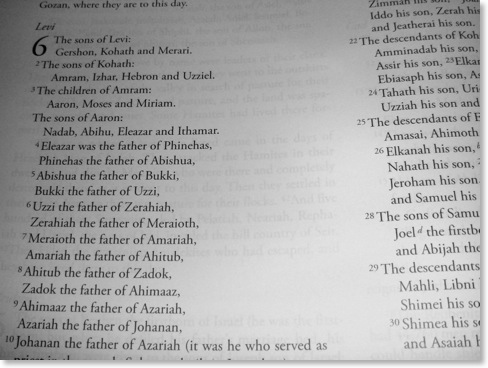

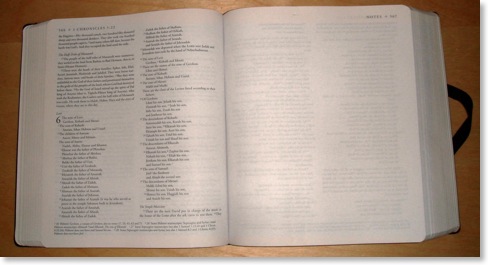

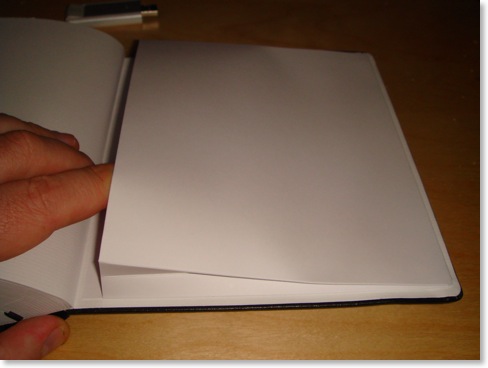

First Look: Zondervan's NoteWorthy Bible

The official Zondervan description reads as follows:

Bible users, take note! With its unique design featuring blank right-hand pages, this Bible offers plenty of room for note taking. An accordion pocket inside provides added storage for loose notes. And an elastic band provides closure so you can keep everything securely in place.

Here are Theophrastus’ comments on the NIV Noteworthy Bible:

(a) Don't use this edition for taking notes. The bleed-through on the paper is so bad I can see down three pages. Since this is not a true interleaved edition (with a double-sided blank page of paper between each double-sided printed page of paper) your ink marks will mar right through the other side.

(b) Tiny font. The font size of the Little Oxford Bible is just five point, but the font size of the Noteworthy NIV appears to be slightly smaller than that. Thanks to my near-sightedness, I can read the Little Oxford Bible without magnifying glass, but I can't say the same Noteworthy NIV.

(c) Relatively generous inter-line spacing. Double column. Square size.

(d) Binding claims to be bonded leather but feels like slightly stiff paperback to me. No one would confuse this with a moleskin notebook.

(e) The elastic on the the outside binding makes it look like this binding is designed to fail! It also give the bible a slight fetishistic look -- maybe it is designed for folks who like to wear latex and elastic.

(f) The internal paper pocket on mine is already failing and I haven't put anything in it.

(g) The left top margin has the page number, an ugly 4-fold diamond mark, the book, name and chapter/verse, but the right top margin only says "notes", the diamond mark, and the page number, making it somewhat more difficult to find sections than one might desire. On the other hand, bleed-through on the Bible is so bad that one can simply read the mirror-image of text on the next page.

(h) No bonuses (no maps, no concordance, no cross-references, no book introductions) except for a half-page table of weights and measures.

All-in-all, I can see no use for this volume except as a fashion accessory among the Goth set.

A Horse Bible? Really?

What girl doesn’t love horses? Filled with beautiful features and photographs, horse lovers will be inspired by this NIV Bible

Really?

Note that I’m posting this on April 7, not April 1. Seriously.

The Wild About Horses Bible is aimed at girls ages 9-12. So, let’s get this straight: we have soldiers’ Bibles, nurses’ Bibles, firemen’s Bibles. And now we have little-girls-who-love-horses Bibles.

Really?

And yet, after four years, I still can’t get a wide-margin TNIV!

Is the niche for a horse Bible really greater than the one for a wide margin TNIV Bible? Really?

I mean, I’ve asked for a wide-margin TNIV for a number of times. I know lots of other people who have, too. But we’ve always been told the potential market for such a Bible simply isn’t big enough. So do you mean to tell me that a larger number of girls ages 9-12 have been beating down Zondervan’s doors for a horse Bible? Really?

Maybe there’s warrant for a Bible like this. Technically horses occur 200 times in the NIV. Of course, goats occur 173 times and sheep show up 208 times. When will we get a sheep Bible, too? Seriously?

Thanks to Jay Davis for alerting me to this.

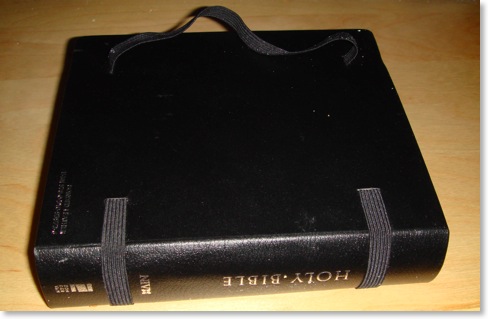

Sometimes You Just Can't Go Back...So Much for the NASB

And such is life.

Kathy sat me down on the couch this morning, and in no uncertain terms told me, “You can’t teach with whatever translation you’ve used the last two Sundays anymore!”

“Why not?” I sheepishly asked. Although I knew better. I had read the word “booty” from that Bible in front of forty people in our Bible study to the snicker of some and to the red face of my wife. Who uses that word anyway--pirates?

She went on to tell me that every time I read anything from my Bible, it was hard to understand and too different from anything anyone else was reading from. She said, “No one could even follow you!”

I reached for the Bible to which she was referring. I opened it up and showed it to her. “But I like this Bible. It has wide margins. I teach better when I use it.”

“Better for you, maybe, but not for anyone else. So you have to decide--are you going to teach in a way that’s easier for you or easier for those listening to you?”

Here’s what happened: two weeks ago, I did the unthinkable--I went back to my NASB for teaching our Sunday morning Bible study. I taught from the NASB for almost two decades, and then in 2005, while teaching a half year study on Romans, I realized I was spending more time explaining the English of the NASB than explaining what Paul actually said in Romans. I have always been an advocate of modern language translation, but I always felt that in a teaching setting, I would be able to use something a bit more formal. I quit doing that in 2005.

Since then I’ve used a variety of translations--going first to the HCSB and then the TNIV as my primary teaching Bible, but also using the NLT quite a bit and even the NET Bible.

...But I was frustrated. Part of my method all those years involved taking notes in a wide margin edition, and then using that edition when I’m teaching. I carried notes on paper, too, but the subset in my margins were little reminders of the most important information to get across.

Two decades ago, my goal had been to study biblical languages to the point that I no longer needed translations at all. I always carry at least my Greek New Testament with me, but I have two problems with totally abandoning English translations: (1) I simply don’t have every word in the NT in my working vocabulary. Yes, I can prepare a passage beforehand to teach from. But the first time I think of another passage to look at, or the first time someone says, “What about this verse?” I look at that and can translate everything except those two words. So it’s never been practical on the fly to try do that exclusively--at least not yet. And (2), I’m hopefully a bit humbler now, but I recognize that my “on the fly” translation, even if I know every word, is not necessarily better than a standard translation produced by a committee made up of people who are surely smarter than me.

So I continue to use both, using a translation as a primary text when I’m in front of others.

After abandoning the NASB, the translation I’d used since I was thirteen-years-old, I assumed I’d be able to get one of these more modern translations in a wide-margin edition. No such luck. So I thought I’d be patient and wait, but now after three and a half years, still no luck.

Sunday before last, I did what I had been tempted to do many times before, I taught from my trusty old Foundation Press wide-margin NASB. It felt good. I felt like I was spending time with an old friend. And even teaching from Isaiah 38-39, I managed to get away with it, partly by letting people in my class read sections that were...what can I say...a bit awkward sounding. But I made it, I felt like I was a better teacher, and I planned to go on and use my trusty NASB for a second week.

Then this past Sunday, we were running short of time as is often the case. With only a couple of minutes to go, I offered to read vv. 11-12 of Isaiah 53. As I begin to read...As a result of the anguish of His soul...I can already see it upcoming in v. 12 in my peripheral vision. My Servant, will justify the many, As He will bear their iniquities... This is what I noted in my preparation that I absolutely must not read publicly...Therefore, I will allot Him a a\portion with the great... I tried to think of all the other translations that I looked at ahead of time. What word did they use for שָׁלָל? Spoil (HCSB, ESV, JPS, NKJV, NRSV, REB), spoils (TNIV, NET)...it was right there swimming about my brain, but I couldn’t remember. And then I read it... aloud:

And He will divide the booty with the strong

I heard chuckles. I could see heads lifting up, including my wife’s. I knew what they were thinking. Did he just say... ? Surely not. No one except for teenagers and pirates say that.

So, the heart-to-heart talk this morning came as no surprise. She had all the conviction of Sarah telling Abraham that Hagar had to go, so who was I to argue with her?

So, I’ll go back to my non-wide-margin Bibles, and wait hopefully that one day, I’ll get a wide margin Bible in a modern translation. But what do I use this Sunday? For the last couple of years, I’ve used TNIV on Sundays mostly, and the NLT during the week. But sadly, I have doubts about the staying power of the TNIV. So maybe this is simply the time to switch.

I use the NLT with my college students midweek because not all of them are believers, and the NLT has the most natural conversational English of any major translation. As I used it tonight with a class, I had to ask myself why I couldn’t use it on Sunday mornings, too? And I don’t have a good answer for that. So maybe this is the crossroads in which I simply need to make the NLT my primary public use Bible. I may have been held back by nothing more than my own traditionalism, but after listening this past week to Eugene Peterson’s Eat This Book, I’m more convicted than ever to present the Scriptures in common, ordinary language, and not the language of heavenly-portals-loud-with-hosannas-ring.

But what do I use? There’s still no wide-margin NLT. I’d certainly want the 2007 edition. So what are my options?

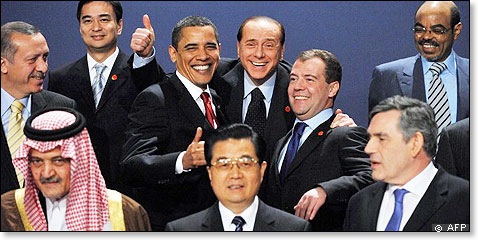

Breaking News from the G20 Summit: The Presidential Gang Sign Is Back

Also seen in the above picture giving the PGS is Italy’s Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi.

Sadly, look at poor Russian President Dmitry Medvedev on the far right:

Obviously, he’s not a full member yet.

What? You aren’t familiar with the Presidential Gang Sign? Well then, click here to read my post on the subject dating all the way back to 2004.