The NASB & the Rejection of Markan Priority

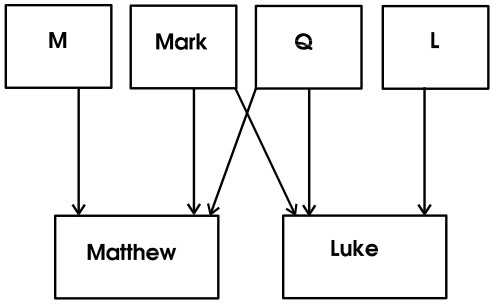

Markan priority--the idea Matthew and Luke independently used Mark's gospel as a starting point, along with the so-called Q source and their own independent traditions--is almost universally accepted in biblical scholarship across almost all theological persuasions.

Consider the late F. F. Bruce on the subject in his article on the Gospels in The New Bible Dictionary:

This finding [the idea of Markan priority], which is commonly said to have been placed on a stable basis by C. Lachmann in 1835, depends not merely on the formal evidence that Matthew and Mark sometimes agree in order against Luke; Mark and Luke more frequently against Matthew; but Matthew and Luke never against Mark (which could be explained otherwise), but rather on the detailed comparative examination of the way in which common material is reproduced in the three Gospels, section by section. In the overwhelming majority of sections the situation can best be understood if Mark’s account was used as a source by one or both of the others. Few have ever considered Luke as a possible source of the other two, but the view that Mark is an abridgment of Matthew was held for a long time, largely through the influence of Augustine. But where Matthew and Mark have material in common Mark is fuller than Matthew, and by no means an abridgment; and time after time the two parallel accounts can be much better explained by supposing that Matthew condenses Mark than by supposing that Mark amplifies Matthew. While Matthew and Luke never agree in order against Mark, they do occasionally exhibit verbal agreement against him, but such instances mainly represent grammatical or stylistic improvements of Mark, and are neither numerous nor significant enough to be offset against the general weight of the evidence for Mark’s priority.

In seeking to confirm Wilkin's statements from 1995, I have been in correspondence with a person at the Lockman Foundation over the past couple of weeks in regard to this subject. Although I was not given permission to quote any of the statements from the representative of the Foundation as they consider them private correspondence only to me, I am allowed to confirm that the rejection of Markan priority is indeed a conviction on the part of the NASB translators.

What difference would it make whether a translator holds to Markan priority or not? Well, I have to walk a bit of a discretionary tightrope here regarding the exact nature of the explanation given to me by the representative of the Lockman Foundation. Suffice it to say, at the very least, it involves (according to them) how a translator might view parallel accounts between the synoptics that contain conflicting information. Are they the same event with actual conflicting details or are they two separate, but similar events? This, evidently, is the issue to the translators. Also, there is concern on the translators part that adherence to Markan priority may affect one's view of inspiration. I can't say much more than that as I may have already relayed more than what is appropriate in the request given to me for confidentiality, although I have attempted to be vague in the statements immediately above. I wish I could be more specific regarding the explanation given to me by the Lockman Foundation.

But I have a few questions for the readers of This Lamp. (1) Am I late to this information, or has anyone else ever heard of the rejection of Markan Priority by the NASB translators? (2) Granted the early church held to a position of Matthean priority, but as far as I know, most biblical scholarship--including Evangelical scholarship--rejects the traditional position in favor of Markan priority. Therefore, how widespread is a rejection of of Markan priority among respected scholarship? (3) As I look at the list of other translators for versions such as the ESV, NLT, TNIV, NET, HCSB, etc., I cannot imagine a unanimous rejection of Markan priority on any of these other committees. Am I simply mistaken? And finally and most importantly, (4) would acceptance or rejection of something like Markan priority truly make a difference in the accurate translation of the Synoptic gospels? Would not an honest translator simply render the text as it is?

For the record, I believe Markan priority is the best offered explanation of the so-called synoptic problem. Frankly, I'm surprised that the entire committee of a modern translation would have unanimous and wholesale rejection of it. Your thoughts are welcome and encouraged in the comments.