HCSB Minister's Bible to Receive Updated Text in Early 2010

This post has been relocated here:

http://thislamp.com/?p=1315

Please continue any discussion at the new location.

"Revised" HCSB Printed Texts Slated for 2010

http://thislamp.com/?p=1548

Please continue any discussion and redirect any known links to the above URL.

A Comparison of the HCSB with Other Major Translations [Edwin Blum]

A Comparison of the HCSB with Other Major Translations

Abstract: Dr. Edwin Blum

The Holman Christian Standard Bible is a new modern translation based on the latest Hebrew and Greek texts. It was produced with the Accordance Bible software program and widespread use of the internet. Electronic editions of BDAG, K-B, reference tools, and translations greatly aided the development of the HCSB. Over one hundred scholars participated in the translation. The HCSB uses what we call an optimal equivalence translation philosophy and seeks to be gender accurate. In comparison with existing translations, the HCSB has improvements in accuracy, vocabulary choices, formatting, and style. It is the leanest modern translation with a word count of 718,943. It has more footnotes and textual information than any major translation and has a system of Bullet Notes to aid the reader. Yahweh is used in passages where the name of God is discussed in the OT, and Messiah is used in NT passages for the translation of christos where the subject is the Israelite deliverer. The result is a Bible that is accurate for study and reads well for personal use and corporate worship.

Introduction

To compare the HCSB with other major translations, we must define the term. What is a major translation? If this were a paper read at SBL, the major translations considered would be NRSV, REB, NAB, and NJB. These are highly esteemed but are not widely used by evangelical Bible students. For our purposes, the major translations we are using as comparisons are the NIV, NLT (second edition of 2004), and ESV. William Tyndale’s (1494?-1536) tradition, which includes the KJV, NKJV, NASB, RSV, and NRSV, will be represented by the ESV. Some may not be aware of Tyndale’s legacy to the 1611 KJV. Eighty-three percent of the KJV New Testament can be attributed to him. Of the books that Tyndale completed, the KJV Old Testament represents about 76% of his work. The NIV, NLT, and HCSB represent different translation streams. The TNIV, NET, and The Message are omitted from this comparison as they do not have a large market share at this time.

The HCSB was not “planned and sponsored by the Sunday School Board of the Southern Baptist Convention in 1998” as one website claims. The origin of this translation goes back to Dr. Art Farstad, who was the Executive Editor of the NKJV. On his own, he began working on a modern language edition based on the Majority Text, which he first called Tyndale 21 and later Logos 21. From 1995-1998 this project was funded by a foundation called Absolutely Free. Holman Bible Publishers purchased the rights to Logos 21 and hired Dr. Art Farstad as General Editor in April 1998. However, the translation Art was asked to oversee was not a majority text translation but a new translation based on the critical text. He died in September 1998, and Dr. Edwin Blum was named as his successor. The goals, purposes, and translation philosophy are outlined in the introduction to the HCSB, which can be found in every printed product.

The HCSB was completed in 2004. The NT of the NIV was finished in 1972 and the OT in 1977. This means that the NIV was completed before the days of the personal computer. It was completed before the internet was used to transmit documents between scholars and editors. It also means that the NIV represents the state of scholarship at the time of 1972-77. For example, the standard Hebrew lexicon in use was the Brown, Driver, and Briggs lexicon published in 1906. HCSB was able to use the new 5-volume Koehler, Baumgartner, and Stamm lexicon (HALOT, 1967-1996).

The theological word books such as Jenni-Westermann’s TLOT, the 15-volume TDOT, the Dictionary of Classical Hebrew, NIDNTT, and NIDOTT had not been published when the NIV was produced. Many major commentaries were also published in the interval between 1977 and 2004. For example, many volumes in the Anchor Bible were finished during this period. Milgrom’s three-volume work on Leviticus in the AB, which represents a lifetime of Jewish scholarship on this book, was completed in 2000.

The NIV translation committee changed 7% of the NIV text when they made the TNIV revision. While many of the changes made were gender changes (1.68% according to the TNIV committee), this means the scholars felt that 5.32% of the NIV needed an improvement. This 5.32% included changes that were “textual, programmatic, clarity issues, sentence structure & grammar, and footnotes & headings.” This is according to the TNIV website. So more than 5% of the NIV needed an improvement since 1977. Some of these changes reflect what can be seen in the HCSB.

Translation Philosophy

In practice translations are seldom, if ever, based purely on formal or dynamic/functional equivalence. Rather they are mixed, with a tendency in one direction or the other. Optimal equivalence is our attempt to describe a translation philosophy recognizing that form cannot be neatly separated from meaning and should not be disregarded. It should not be changed unless comprehension demands it. For example, nouns should not be changed to verbs or the third person “they” to second person “you” unless the original sense cannot otherwise be clearly conveyed. The primary goal of translation is to convey the sense of the original with as much clarity as the original text and the target language permit. Optimal equivalence appreciates the goals of formal equivalence but also recognizes its limitations.

Gender Issues

Since 1977 the gender controversy has become a major issue among Bible translators. The goal is to accurately translate Scripture. The ESV and HCSB follow the Evangelical Guidelines of May 27, 1997 for translation of gender-related language in Scripture. The NIV was done before there was a lot of gender sensitivity. One estimate is that there are 800 places in the NT of the NIV that use masculine language where the Greek text would allow a more generic or neutral translation. A classic example is Romans 12:6-8. In this passage, the NIV has inserted nine male pronouns or the word “man” where the Greek text does not require it. The NIV reads, “We have different gifts, according to the grace given us. If a man’s gift is prophesying, let him use it in proportion to his faith . . .” The HCSB is gender accurate and has no male language inserted in this passage. The HCSB reads, “According to the grace given to us, we have different gifts: If prophecy, use it according to the standard of one’s faith . . .” The TNIV has gone overboard to avoid gender insensitivity and is more gender neutral. We would claim that the NIV is gender biased, the TNIV attempts to be gender neutral, and the HCSB is gender accurate.

The NLT shares to a lesser degree the gender neutrality of the TNIV. Comparing 17 English translations in 115 gender-sensitive passages, involving various kinds of grammatical constructions, yields the following percentage of gender inclusive translations:

KJV 8%, RSV 10%, NKJV 13%, NASB 14%, NIV 17%, ESV 24%, HCSB 25%, NLT ’04 67%, TNIV 79%, NRSV 84%, CEV 96%. Clearly we believe a gender inclusive translation is correct 25% of the time—more than the KJV, but much less than the TNIV.

The result of a bias toward gender inclusivity is that many masculine terms are removed, muted, or changed. The Greek NT has anthropos 548 times and aner 216 times. Anthropos has a larger semantic field and should be translated as “human” in many contexts, but aner refers to a male person. Of the 216 times it occurs in the NT, NLT has removed, replaced, or changed it 43 times, eg. Ac 27:25 and Rm 11:4.

In the OT there are five major words for humanity. Adam means a man or human, and it occurs 546 times. Ish means male, man, or husband, and it occurs 2,199 times. (The female form is ishshah and occurs 775 times.) The Hb enosh occurs 42 times, and the Aramaic enash occurs 25 times, making a total of 67 occurrences. Gebher means manly or vigorous, and it occurs 66 times. So the total number of Hebrew words for men, males, or man is 2,878. If we only look at the word ish, which is the clearest term for male, it occurs 2,199 times. Yet the NLT only has the words “man, man’s, men, and men’s” a total of 1,617 times. For example, in Lv 20:2-5 ish occurs five times, but they change it to the plural words “they” or “them” instead of using the word “man.”

In many places, the more gender inclusive translations change “fathers” to “parents.” The book of Proverbs is no longer a father’s instruction to his “son”; instead, it’s written to his “children.” The HCSB and ESV have not followed this trend and have translated the text more accurately than the TNIV or the NLT.

Accuracy or Translations of Certain Problematic Words

The following words are representative of the accuracy of the HCSB.

1. The Greek word doulos occurs 124 times in the Greek NT. Many Bibles have translated it as “servant” or “bondservant.” ESV uses servant in the text, but they attach a footnote that reads, “Greek bondservant.” NIV and NLT alternate between “servant” and “slave.” The translation of doulos as servant is faulty (cf. BDAG, p. 260) and causes people to miss a significant Pauline metaphor. HCSB uses slave. There is a significant difference between a servant and a slave. Paul says, “. . . You are not your own, for you were bought at a price . . . ” (1Co 6:19b-20)

2. The key term torah occurs 223 times in the Hebrew Bible. Most Christian Bibles consistently translate it as law. Most Jewish Bibles normally use instruction or teaching. “The majority of present day exegetes translate tora as instruction, education, teaching” (TDOT, XV: 615). If we compare the translation of torah in Ps 1:2; 19:7, and 37:31 in the major Bibles we note the following:

• ESV – law

• NIV – law

• NLT – law and instruction

• HCSB - instruction

3. God’s personal name, YHWH, occurs 6,828 times in the Hebrew Bible. In English Bibles LORD is commonly used following the LXX tradition of rendering it with kurios. However, LORD is not a name; it is a title. It has been argued that the use of YHWH (or Yahweh) will offend Jewish people. Very orthodox Jews will not even vocalize the word “God,” preferring the use of “G-D.” However, some modern Jewish translations have used YHWH. French Protestants as well as the Moffatt translation have used “The Eternal” as a name. B. Waltke prefers to translate the name as “I AM” (OTT, p. 365.) If we compare the translation of YHWH in major translations we see the following:

• KJV – Jehovah 4 times

• RV (1881) – Jehovah 10 times

• ASV (1901) – Jehovah 6,777 times

• NJB – Yahweh 6,342 times

• NLT – Yahweh 7 times (all in Exodus)

• REB, NASB, NIV, NKJV, TNIV, ESV – all use LORD

• HCSB – Yahweh 75 times (first printing); currently 467 times; the 467 uses are where the name of God is praised or discussed. For example:

“I am Yahweh, that is My name; I will not give My glory to another or My praise to idols.” Is 42:8

“Yahweh is the God of Hosts; Yahweh is His name.” Hs 12:5

“May they know that You alone—whose name is Yahweh—are the Most High over all the earth.” Ps 83:18

4. In the HCSB NT, christos is translated Messiah where there is a Jewish context (cf. BDAG, p. 109). An example is, Mt 16:16, which reads “Simon Peter answered, ‘You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God!’” NLT agrees with HCSB, but ESV and NIV translate this as “the Christ.” (TNIV has changed this to “the Messiah”.)

Vocabulary Choices

The NIV, NLT, and the HCSB use a more modern and American vocabulary. The ESV retains some of its British heritage by including dated or archaic language. Here are some examples:

• ails Ps 114:5

• alms Lk 11:41 (8 total occurrences)

• barley was in the ear Ex 9:31

• bosom Ex 23:8 (12 total)

• chide Ps 103:9

• disdained 1Sm 17:1

• ears of grain Gn 41:5 (4 total)

• fodder Gn 24:25 (7 total)

• he-goat Pr 30:31

• morsel Gn 18:5 (13 total)

• she-bear Pr 17:12

• whoredom 2Ch 21:11 (13 total)

The NIV and TNIV also include some archaic or unusual word choices:

| abound |

spurn | |

| alas | strode | |

| astir | suckling | |

| befuddled | thus | |

| bosom | toil | |

| deluged | to no avail | |

| kindred | unkempt | |

| naught | unmindful | |

| profligate | unsandaled | |

| reckon | unto | |

| rend | unwary | |

| self-abasement | upon | |

| shall | vaunt | |

| slew | vilest |

When we compare six specific words among the major translations, we see the following:

1. Tithe - an old English word for a tenth.

• KJV – 40 times

• ESV – 41 times

• NLT – 22 times

• NIV – 15 times

• HCSB – 0

2. Behold

• KJV – 1,326 times

• ESV – 1,106 times

• NIV – 6 times

• NLT – 0

• HCSB – 0

3. Lepers, leprous, leprosy – should not be used today because of the confusion with Hansen’s Disease. Hansen’s Disease does not grow on clothing, walls, or other objects as mentioned in Lv 13-14.

• ESV – 68 times

• NLT – 34 times

• NIV – 33 times

• HCSB – 0

4. Shall – is fast disappearing in modern American usage (cf. B. Garner in Modern Legal Usage, 2nd ed., pp. 939-941).

• KJV – 9,838 times

• ESV – 6,389 times

• NIV – 467 times (TNIV – 480 times)

• NLT – 8 times

• HSCB – 0

5. O – is an old spelling of the word “Oh” and is considered archaic when used before a name in direct address, e.g. “O King, live forever.”

• KJV – 1,065 times

• ESV – 1,129 times

• NIV – 978 times (TNIV - 64 times!)

• NLT – 743 times

• HCSB – 0

6. Strong drink – is a 14th century term. HCSB uses the correct term beer. The average reader would understand strong drink to be a distilled product rather than a fermented one, but distillation was not discovered until the ninth century AD.

• KJV – 22 times

• ESV – 23 times

Verbose or Lean?

The word count of the Hebrew and Greek text in the standard critical editions is 545,202. Let’s compare this to some major translations.

• Original KJV |

774,746 |

• Current KJV |

790,676 |

• ESV |

757,439 |

• NLT |

747,891 |

• NIV |

726,109 |

• HCSB |

718,943 |

That means the ESV uses 38,496 more words than the HCSB to convey the source text of 545,202 words. As a side note, NASB95 is considered by some to be a fairly literal translation, yet its word count is 775,861. So it uses 56,918 more words than the HCSB.

Reader Helps

1. Bullet Notes - the HCSB has an appendix of 145 words or phrases that average readers might need some help in understanding. These words, e.g. Asherah, Ashtoreth, or atone, are marked with a bullet on their first occurrence in a chapter of the biblical text. When readers see a bullet in the text, they can refer to the appendix if they want to learn more about the term.

2. Footnotes – The HCSB has the following notes:

• 1,586 textual notes

• 5,161 alternate readings

• 843 explanatory notes

• 27,565 cross references

• 237 OT citations in the NT

The NIV and ESV have far fewer notes. For example, the NIV has no textual notes in Gl, Php, 2Tm, and Ti. HCSB has 16. The NLT does have extensive notes, but often a critical term like atone or atonement is left without explanation. In Nm 25:3 there is no help given on Baal of Peor. And in Lv 13:39, ESV uses the term leukoderma with no footnote to help the reader.

3. Formatting – In addition to special formats for poetry, dynamic prose, OT quotes, and using new paragraphs for new speakers, care has been taken in the database of the HCSB to avoid what is called widows and orphans in the typesetting process. Single words wrapping to the next line are avoided so that units of thought are kept together. This produces a Bible page that is more readable and pleasing to the eye.

In summary, the HCSB is more accurate than the NIV, ESV, or NLT. It reads well and has a modern, American vocabulary. Particular attention was devoted to clear and contemporary word order and formatting. The HCSB is more up-to-date in scholarship, and it offers more help and notes to the readers so they can understand what God is saying to them.

The most famous verse in the Bible is Jn 3:16.

NIV translates it as:

“For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.”

Similarly, ESV has:

“For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life.”

NLT uses:

“For God loved the world so much that he gave his one and only Son, so that everyone who believes in him will not perish but have eternal life.”

However, the HCSB correctly translates the Greek houtos:

“For God loved the world in this way: He gave His One and Only Son, so that everyone who believes in Him will not perish but have eternal life.”

Craig Keener in his commentary The Gospel of John, Vol. 1:556 supports our translation when he says, "Some could understand English translations (God ‘so’ loved the world) as intending, ‘God loved the world so much’; but John's language is qualitative rather than quantitative. Houtos means ‘this is how God loved the world’; the cross is the ultimate expression of his love." His footnote reads, "On the syntax in 3:16 yielding ‘in this way,’ see esp. Gundry and Howell, "Syntax."

New Journaling Bibles on the Horizon (HCSB, NRSV)

There are two new editions in the HCSB, called the HCSB Notetaker’s Bible, set for release very soon (October 8). One is referred to as a Men’s edition (ISBN 158640475X) and comes in a decorative brown hardcover. A women’s edition in mauve/olive green is also available (ISBN 1586404768).

There are no page spreads available for viewing yet, but these images of the covers are available at the CBD website (click on each image to see each Bible’s respective page):

Really, B&H should have probably avoided calling these “Men’s” and “Women’s” editions. I’m certain there will be some women who want the brown, and you never know who might want the other edition as well.

The CBD website also includes the following ad copy:

In an age when people can take notes using a variety of electronic media, there has emerged a countertrend whereby people want to journal in their won handwriting. The Notetaker's Bible features wide margins with subtle ruled lines, helpful center-column cross references, a concordance, and best of all, the largest point size among all Bibles of this kind. Handsomly bound for a man's taste. [The women’s edition says “Beautifully bound in with a woman's taste in mind.”]

Features include:

- The largest point size among Bibles of this kind

- Easy-to-navigate center-column references

- An easy-to-use concordance

- Ribbon marker

- Words of Jesus in red

- Translation footnotes, and exclusive HCSB bullet notes

Both Bibles measure 9.38 x 7.25 x 1 and contain 1280 pages. Biblical text will be presented in double columns. Personally, I feel that if a Bible of this sort uses double columns of text, there should be equal amounts of spacing for written notes for each column. We will have to see if B&H Publishing thought of this.

While I was on the CBD website, I also noticed an NRSV Notetaker’s Bible (ISBN 0195289226) to be released from Oxford University Press in 2009. There aren’t a lot of details yet, and no image that I could find even of the cover. But according to the CBD site the Bible will be paperback, contain 1296 pages, and measure 8 x 6.3 inches.

The Return of the Disciple's Study Bible, Now in HCSB

The Disciple’s Study Bible was a project from Holman Bible Publishers two decades ago that took the NIV text and added study notes based around a core set of doctrines. Although there was enough content in the Disciple’s Study Bible to make it a self-contained resource on its own, the real value of it could be found when using it in conjunction with the accompanying workbook and leader’s guide. The workbook itself had 65 individual lessons for use in private or group settings.

After seeing the Bible on eBay, I looked on Amazon to only confirm that the Disciple’s Study Bible is now out of print. I wasn’t overly surprised to learn this as I had not seen it on store shelves for quite some time. It is still available used on Amazon ranging in asking price from $35 to $250 according to the edition.

I pulled my copy of the Disciple’s Study Bible off the shelf along with the workbook and flipped through both. Honestly, it’s been years since I looked through either, but as I surveyed the content, I thought to myself that it would be very useful in a church discipleship context. And then it struck me that the Disciple’s Study Bible would be a perfect fit for Lifeway’s in-house translation, the Holman Christian Standard Bible. This would mean that B&H could produce the Bible without having to pay licensing fees to another company as had been done when it was based on the NIV.

So I shot off a message to B&H Publishing customer service and suggested that the Disciple’s Study Bible be retooled for the HCSB. Evidently great minds think alike because I got a response back this morning letting me know that there are indeed plans to re-publish the Disciple’s Study Bible in the HCSB, and it is slated to be released late in 2009.

Since there is a revision to the HCSB slated for 2009, I would assume that the new edition of the Disciple’s Study Bible will contain the newest text.

Blum on the HCSB at Anwoth

Blum is incredibly transparent about disagreements among the translators and even the publishers. Also, Blum goes to great length to distinguish the HCSB from other translations and combat the notion that this is a "Baptist Bible" (Blum himself is not Baptist). You must read the entire interview, but here are some of the more surprising elements about the HCSB and Blum that were revealed:

- A second edition of the HCSB will be released in 2009.

- Why "beer" is used instead of "strong drink."

- When the project first started by Arthur Farstad, there were parallel tracks for the HCSB in which there were to be two New Testaments, one based on the Majority Text and one based on the Nestle-Aland text. The Majority Text project was dropped after the death of Farstad.

- Southern Baptists (does he mean Lifeway here?) tried to BUY the NASB from the Lockman Foundation three times--and it almost went through!

- We finally get a better understanding of the relationship of the HCSB to the Logos21/Living Water Gospel of John.

- Blum explains the complicated history behind the name "Holman Christian Standard Bible" and reveals other names considered. Every name including the current one has legal issues, though.

- According to Blum, "Holman" is already being downplayed in the logo and will soon disappear altogether leaving the designation simply "CSB."

- Mounce sent Blum an email stating that the HCSB is the first translation to get John 3:16 right. (I think I said that, too, a while back!)

- Currently, the HCSB uses the designation "Yahweh" instead of the traditional "LORD" (all caps) 75 times. In the 2009 revision, that number will grow to 400.

- Awkward terms like "deluge" and "atmospheric domains" will NOT appear in the 2009 revision.

- Blum explains the decision to go with the half brackets around some words that are added for clarity, but admits he was not in favor of doing it.

- The HCSB translators hate red-letter editions, but publishers love it.

- Farstad was not a Baptist but was a Brethren. Blum is Presbyterian. Only about 1/3 of the translators were Southern Baptist. This hardly justifies the HCSB's reputation as the "Baptist Bible."

- Blum claims that the HCSB is outselling the ESV two to one.

- Agrees that the HCSB website is hard to use.

Good stuff. Really good stuff.

Missing My Wide Margin NASB

Frequent readers of This Lamp will remember that although I've always been an aficionado of Bible translations, I used the NASB for almost two decades in teaching and preaching settings until I became convicted a couple of years ago that the formality and literalness of the translation itself was getting in the way of what I was trying to teach. Since then, I have primarily used the TNIV in public, but I've also used the HCSB and NLT to a certain extent as well. And often even when needing to carry a translation to a setting where I wasn't presenting, I tended to pick up my TNIV.

But yesterday is a good example of this "change" in my habits. I've been meeting a friend of mine for breakfast for a couple of years now, and we usually read a book together and discuss it over bagels. Over the last few weeks we've been reading Bonhoeffer's Cost of Discipleship. Yesterday as I was heading out the door to meet for breakfast, I grabbed a Bible as I always do. But instead of grabbing the TNIV Study Bible which has been my practice for a few months, I picked up my wide margin NASB.

Doesn't the TNIV Study Bible have notes? Sure it does. But the notes in my NASB are my notes. These notes are the facts and insights that stuck out to me. These notes are the triggers I used to discuss the text when I was teaching it last. The TNIV Study Bible is the first study Bible that I have ever consistently carried with me. It's notes are helpful, but I find that I don't automatically turn to them. I look at them if I need to look something up and hope that the information I need is there.

After using other Bibles for over a year and a half now, I have to admit that i really miss my wide margin NASB. And I don't think it's the NASB that I miss so much, although I will always have a great familiarity with it. What I miss is the ability to refer to my notes, to refer to a tangible experience of having spent time--studied and wrestled--with a particular passage before. I don't have notes on every page of my Bible. But the notes that I do have are footprints that I was there, evidence that I stopped and camped out a while, as opposed to merely passing by.

I stay in a continuing conundrum. I really do feel committed to public use of a contemporary translation. And I would prefer a gender-accurate, non-Tyndale translation when presenting in front of mixed audiences. But no usable wide margin edition of a contemporary translation exists that meets these factors. There is no wide margin NLT and the only wide margin TNIV offering limits writing space to one column on a two column page and has paper too thin for extensive use. I might be willing to settle for the HCSB even though it is not gender accurate, but the pages in its only wide margin offering are so thin that they curl when writing on them.

At this point, I would like a new wide margin Bible (leather, of course) in a contemporary translation--any translation. I'm willing to transcribe my notes even a third time. TNIV? NLT? NET? HCSB? Something else? At this point, I'm not even overly concerned with the exact translation, in spite of the fact that I have my personal favorites and feel some are better suited for teaching than others. Whichever publisher first delivers a wide margin edition in one of these translation wins--at least with me.

Every Sunday morning when I leave for church, I push aside my wide margin NASB in favor of the TNIV Study Bible. Despite the fact that as I've studied a passage that I will be teaching I've taken diligent notes in the margins of my NASB, I've been forced to create a subset of these notes in the anemic margins of the TNIV Study Bible or in whatever white space I can manage. But the temptation to grab my trusty NASB and run remains. And I wonder if this temptation is growing stronger?

Comparing Apples to Pupils: Zechariah 2:8 in the HCSB, NET, and NLT

also all Hebrew below has been transliterated as RapidWeaver seems to continue to have difficulties correctly rendering Unicode Hebrew]

I've stated on a number of occasions how much I respect the HCSB translators' decision to regard accuracy over tradition in many of the translation's renderings. In my review last year of the HCSB, I remarked that although the HCSB courageously breaks with traditional wording of a favorite verse like John 3:16, it does so strictly for the sake of better communicating the meaning of that verse which is easily misunderstood in most translations.

And so it is with Zech 2:8 which was part of our Bible study yesterday at church.

Zechariah 2:8 |

|

Traditional Renderings |

Accurate Renderings |

| For thus saith the LORD of hosts; After the glory hath he sent me unto the nations which spoiled you: for he that toucheth you toucheth the apple of his eye. (KJV) | For the LORD of Hosts says this: “He has sent Me for |His| glory against the nations who are plundering you, for anyone who touches you touches the pupil of His eye. (HCSB) |

| For this is what the LORD Almighty says: “After the Glorious One has sent me against the nations that have plundered you—for whoever touches you touches the apple of his eye— (TNIV) | For the LORD who rules over all says to me that for his own glory he has sent me to the nations that plundered you–for anyone who touches you touches the pupil of his eye. (NET) |

Using Accordance, I scanned the KJV to determine that this translation uses the English word apple for four separate Hebrew words in the OT:

- ’ishwon: Deut 32:10; Ps 17:8; Prov 7:2

- tappuach: Song 2:3; 8:5; Joel 1:12

- vat: Lam 2:18

- vava: Zech 2:8

If anything, "apple of his eye" seems to communicate something slightly different in our culture than what was intended in the text. I did a quick survey of my class yesterday as to the meaning of "apple of his/my eye" and most responses were of the "cutesy" variety, often noting the idea of a daughter being the apple of her father's eye.

In Zech 2:8, vava literally means "gate" of the eye; but ultimately, that's too literal for understanding in English. The meaning here is essentially the pupil as the HCSB and NET correctly translate it. McComiskey notes:

In this analogy, the eye is Yahweh's [...] As the eye is extremely sensitive to touch, so God is sensitive to what threatens his people. The statement develops further the important postexilic theme that God will protect his people and allow no hostile intervention. (The Minor Prophets, vol. 3, p. 1061)

In other words, to mess with God's people is like poking a stick in God's eye, so watch out!

One more note: the NLTse translation of Zech 2:8 bypasses the apple/pupil issue to focus on the meaning of the phrase:

After a period of glory, the LORD of Heaven’s Armies sent me against the nations who plundered you. For he said, “Anyone who harms you harms my most precious possession.

But more important than that, of all the most recent translations, only the NLT attempts to correct the tiqqune soferim found in this verse. That is, the ancient Hebrew scribes were offended at the idea of poking a stick in God's eye, so the wording was changed from "my eye" to "his eye." Thus, in the end, according to one's opinion and evaluation of the dynamic rendering "my most precious possession," the NLT may turn out to be the most accurate translation of Zech 2:8 of those surveyed here.

For another look at a tiqqune soferim, see my post on Hab 1:12.

Hands On with the HCSB Minister's Bible

The box cover pictured here describes The Minister's Bible as a single-column/wide margin Bible. I'll go through some of the other features listed on the box and offer a few comments:

Genuine Leather Cover. I'm not certain of the exact grade of genuine leather for this Bible, but it certainly feels like good quality to me. It's a muted black and is quite flexible allowing this Bible to balance nicely, Billy-Graham-style, in one hand. Considering the HCSB Minister's Bible (HMB from this point forward) has a lifetime guarantee, the publisher obviously considers this to be a quality product. I've no doubt that the leather will hold up to the test of time, but I'm not so sure about the actual pages. More on that below.

Large, Easy-to-Read Typeface. Technically the main text uses a 9.8 point typeface. This isn't exactly large print, but it's clear and legible and I can use this Bible in public without my reading glasses, which is always helpful. Also, there's strictly black letters in this Bible. None of that red-letter nonsense.

Two Ribbon Markers. Why doesn't every Bible include two markers? This is quite handy. One is black; the other is red.

Single-Column Format. Any regular reader of this blog knows that a single-column of text is my preferred format in a Bible. The layout here is clean and open and there's no indication of "rushing" the text as in some Bibles to make for fewer pages. There are no cross references to clutter the page and get in the way of note-taking. Textual notes are laid out at the bottom in a smaller typeface.

Extra Wide Margins for Taking Notes. In my opinion, this description is a bit misleading. I imagine the marketing folks simply meant that this Bible's margins are wider than other Bibles. But when I think of a wide margin Bible, I generally see that as a designation of at least an inch of space for note-taking. Therefore, an extra wide margin should be considerably wider--one and a half to two inches perhaps. The one inch margin in this Bible is adequate in most places. There's even much more room for annotations in poetic sections, but longer prose passages, especially in the NT epistles, will leave the person who likes to add notations wishing for more space.

Gilded Page Edges. I liked the shade of gold that was on this Bible when I first bought it. It was a less bright gold color, a bit muted perhaps. However, now after one year's use--and I don't even use it all that regularly--the gold has faded quite a bit. Of course if you want a new Bible that doesn't look new, I suppose this would be a good thing.

Ministerial Helps Section. Perhaps this is one of the HMB's strongest points. In the back of the Bible comes the "minister's manual" with quite a few resources, some of which are actually quite helpful. Here is a list of the features with an occasional comment from myself:

- Pastoral Care: Where to Turn. This is a standard, "When you feel _________, turn to this Bible passage" supposedly for use when counseling those with problems. I suppose this kind of resource is helpful at some level, but really, I hope that most ministers can reference this kind of information off the top of their head.

- "21 Essentials of Authentic Ministry" by James T. Draper. These are helpful reminders from a seasoned pastor and denominational leader. "Never make a decision when you are discouraged or depressed." "Always return your phone calls and answer your mail." "Always be prepared to preach." "Don't flirt with temptation." "Give credit to other people." "When you are wrong, admit it." As the title suggests, there are 21 of these admonitions with explanations. This is probably the kind of wisdom the average pastor should read once a year. I've known some who should read it once a month.

- "Weddings: Guidelines for Premarital Counseling" by Jim Henry. A lot of the wedding/marriage information in the HMB comes from Jim Henry's The Pastor's Wedding Manual (ISBN 0805423133), including these guidelines. Although this information is produced elsewhere, it is still a valuable set of guidelines for what could actually be multiple sessions of premarital counseling with engaged couples.

- Guidelines for Planning Wedding Ceremonies.

- Couples Commitment Form

- "The Kingdom Family Commitment" by Tom Elliff.

- A Classical Wedding Ceremony

- A Contemporary Wedding Ceremony

- "Funerals: When the Death Bell Rings" by Jim Henry. This is handy little resource, primarily for the inexperienced minister on responsibilities and what to do from the beginning of a death notification to the funeral services. It is excerpted from A Minister's Treasury of Funeral and Memorial Messages(ISBN 0805425756) also by Henry.

- Funeral Sermon: "The Teacher Called Death" by Jim Henry. This is the only funeral sermon in the HMB. I suppose it might be handy for extremely short notice.

- "The Invitation or Altar Call" by Roger Willmore

- Commitment Counseling. Topics covered: salvation, baptism, church membership, assurance of salvation, rededication to grow toward spiritual maturity, and commitment to vocational Christian Ministry.

- "The Pastor's Concern for Children" by W. A. Criswell.

- "Reaching Students with the Gospel" by Lynn H. Pryor.

- How to Lean an Effective Parent-Child Dedication Service

- How to Conduct a Worker Commitment Service

- How to Dedicate a Building

- The Christian Year and Church Calendar. I find this interesting because it includes the more traditional calendar dates such as those for the Lenten Season like Ash Wednesday and Maundy Thursday. Obviously, it's primary market for the HMB is Baptist and most Baptist churches do not celebrate the traditional church calendar days--although some do. Intermixed with these dates are specific Southern Baptist dates that are promoted yearly such as Sanctity of Human Life Sunday, Racial Reconciliation Sunday, Citizenship and Religious Liberty Sunday, and World Hunger Sunday among others.

- The Apostles and their History. In my opinion, this is really an odd choice to include with these other items. I really don't know how often in pastoral ministry, a minister will need quick access to a table of facts about the 12 apostles of the Gospels.

- Principles of an Orderly Business Meeting. Unfortunately, this particular guide is only one page long whereas entire books have been written on the subject. I don't know how helpful it will be to have this brief treatment at one's fingertips.

So what are the strengths and weaknesses of the HCSB Minister's Bible? Well, copy on Holman's product page for the HMB describes it as "like having a fine 'preaching Bible' and practical 'minister's manual' in one." And that, of course, is the goal of it. Ministers manuals abound with specific manuals on weddings, funerals, and the like. But anytime I've had to officiate a formal occasion like a wedding or a funeral, I've usually taken my text and affixed to the center of a nice-looking, black leather Bible. I'm sure that lots of folks who don't know better assume that there's some chapter in the middle of the Bible that contains wedding vows. Obviously, this is not the case. The HMB would theoretically allow a person to use one Bible for teaching, preaching, and administering the great services of life. It's a great idea, but it falls short in some areas.

For teaching and preaching. As far as having a nice looking black leather Bible, with a single-column format with clear and readable text, the HMB can't be beat. However, my greatest complaint in this category is its thin pages. While not exactly a thinline Bible, the HMB has well over 1800 pages and yet is only 1.55" thick! To create a Bible with so much content and yet to keep it so thin, Holman had to use incredibly thin paper. In fact, this has to be some of the thinnest paper I've yet to see in a Bible (and I've seen lots of Bibles!). Bleed through is a problem not only with the text, but also with any notes written in the margins. Even ink from Pigma Micron pens which are generally perfect for writing in Bibles shows through the page. Even worse, the pages are so thin that they have a tendency to curl when written upon or even when laid open to a passage for long enough time. If the Bible is closed long enough this curling will eventually go away, but it can be very distracting while trying to stay focused on a particular passage. Further, it makes it very easy to accidently fold the corners of pages, and afterwards, even if they are straightened out, any passages where you've spent a good amount of time will have a slightly worn look to them. Thicker paper would have gone quite a way to making this an excellent note-taking Bible. As an aside, for HCSB aficionados, this is the ONLY wide-margin Bible available in this version as of this writing.

For funerals, weddings, and other services. In regard to funerals, a minister will be better served by obtaining one or two good funeral manuals. It's no secret that ministers don't always create funeral messages from scratch. Often there's very little advance notice for such an occasion. However, a skillful minister can take a generic funeral message and personalize it based on his knowledge of the deceased. And therefore, having access to a variety of these kinds of messages is helpful as a minister might officiate a number of services in any year's time based on a church's population. Therefore, the inclusion of simply one message (although it is a very good message) in the HMB is not going to be all that helpful in the long run.

I used the HMB when I officiated my friend Andrew's funeral last year. But I did not use the sermon included in the Bible. And because of the nature of the accommodations of the funeral home, I was able to take the text of my message in a binder, and the HMB made a very nice Bible with readable type for use in that kind of setting (although in hindsight, Andrew was traditional enough in some areas that he might've preferred the KJV). However, when it came to the graveside service, I found myself using the old trick of paperclipping my text into the middle of the Bible.

So perhaps here is where the HMB could be improved. Graveside services tend to be very short and basic. Why not include a handful of different graveside services in a resource like this? I believe that would be more helpful than one token sermon.

On the other hand, the two wedding services included in the HMB are very good selections. The classical service has the very traditional "I plight thee my troth" and "With this ring I thee wed, and with all my worldly goods I thee endow." But at the same time, the contemporary service has more up-to-date language: "I promise to honor you, to love you, and to cherish you until death do us part." Although it would still be beneficial to have a full wedding manual with a variety of services to choose from, the two included in the HMB would probably serve the majority of services in which the minister would be engaged (no pun intended).

On Saturday, I performed a wedding service for a former student of mine, and I used the HMB and the contemporary wedding service found in it. Overall, the experience was good, and the contemporary service served the needs of the day well. I didn't stick to the outline in the HMB 100%, but I did stay pretty close to it so as not to add any unnecessary bloopers to the wedding video. In that regard, the HMB was very helpful.

At the same time, after utilizing the HMB in actual use during a wedding, I would offer some suggestions for improvement, and in fact, I wonder how well this product was field tested. First, one of my biggest complaints of this Bible from the beginning is that all of these minister's helps are placed in the back. Think about that for a minute. This is an 1800+ page resource, and all of the primary resources are in the last 10% or so of it. What that means is that for public use, the minister will be turned to the very back of the Bible for the entire time. Not only would it look better to an audience to work from somewhere more in the middle, but there's also a practical issue regarding the way the Bible is weighted. If you've ever been in a wedding in any role, you know that standing in front of the church, having to remain perfectly still for possibly an hour or more can be grueling. Now think about the minister for a moment. When I teach or preach, I can move around and pace and stay reasonably active. However, in a wedding service like the one on Saturday, I had to remain perfectly still for well over 40 minutes with my Bible held out before me in my bent arms--no podium. You might think it's not big deal to hold a Bible out in front of yourself, but try it for 40 minutes, and be sure to keep your feet perfectly planted in one position since you've already been informed by the videographer that if you move your left foot off the tape on the floor, you won't be seen in the video. This can be extremely tiring. As we got further along in the service, the fact that I had my Bible opened to around p. 1690 and following gave me a real concern that in a moment of inattention, it could simply fall out of my hand because the weight was so lopsided.

The very simple solution here would be to simply move all the ministerial helps to a section between the Old and New Testaments. Obviously, that's not going to be the direct center of the Bible, but it would help balance the Bible a bit better when using it, especially in formal settings. This seems like a no-brainer after actually using the HMB as it was intended, and this is why I wonder how well it was field tested. I certainly can't imagine anyone suggesting that such placement might confuse some into thinking this material is actually scripture.

Another issue I had during the service was the placement of text on the page. This wasn't an issue when I sat at my desk the day before and read through everything out loud. However, holding the Bible in front of myself, reading from the text, while at the same time attempting to keep good eye contact became a challenge with the text that was at the bottom of the page. Part of the vows and the dedication of marriage itself was right at the bottom which created more of a strain as I tried to look all the way down to the bottom of the page and maintain frequent eye contact. A better solution might be to keep the bottom third to half blank with the service itself in the top portion of the page. This would allow for any post-it notes for reminders or penciled-in information. As it was, I had a tiny order of service for the entire wedding posted to the page facing the first part of the contemporary service. And I had frequent notes throughout in pencil. A spot at the bottom of the page to write some of this would certainly be helpful.

Final thoughts. Ultimately the HMB may suffer from trying to be too many things at once. It's not the greatest Bible for teaching and preaching for the person who wants to write notes because of the thinness of it's paper. And the ministerial helps ultimately seem more representative of a minister's manual than a final solution. These resources are not going to replace the need for one or more good pastoral manuals.

Nevertheless, the idea itself is a good one. Perhaps rather than trying to include all the information found in the HMB, the publishers could concentrate on specific services such as weddings, funerals and dedications. Yesterday, at our church we had a baby dedication. I noticed that our pastor read the charge to the parents and the church from a single sheet of paper. Now, there's certainly nothing wrong with that, and our service went fine. But I thought to myself that there's an almost exact same service and words included in the HMB. Maybe it's just me, but there seems to be something authoritative about holding a Bible--or at least a black leather book--when conducting formal services such as these. To me, this would be the ideal use of a Bible such as this. And it wouldn't hurt to have it in other translations as well. Note: Hendrickson publishes a number of Minister's Bibles in the KJV, NKJV, and NASB, but I don't believe they cover quite the same content. I've heard rumors that Holman might release the Minister's Bible in another translation, perhaps the NKJV. I ran a search on Zondervan's website and found a similar minister's Bible in Spanish, but not English!?

Another idea might be to have a 1000+ page minister's manual covered in black leather with multiple wedding and funeral sermons, dedication services, and other ministerial helps such as the ones found in the HMB. Such a resource might even have room for the New Testament and Psalms to be included as well.

I'll continue to use my HMB now and then, but it's not the primary Bible that I thought it would be when I got it 15 months ago. Nevertheless, it's a useful, although flawed resource. Now if I could just get something like this in the TNIV...

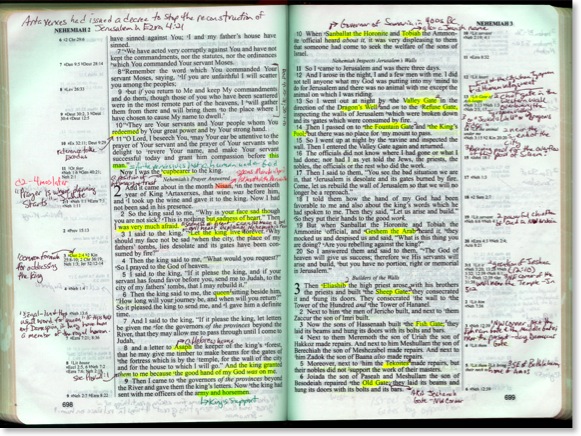

The Grantham Bible Study Method

A Guest Post by Chuck Grantham

Rick has asked me to expand a bit on how I prepare for Sunday School for those who may not read the comments section.

The first thing I should say is that I do not teach a Sunday School class. I do this primarily for myself. On the other hand, I think any group of believers studying the Bible deserve good answers when they have questions, and the Learner Guide in the Lifeway Explore the Bible series, the Southern Baptist Convention’s Sunday School quarterly, cannot possibly address all the questions that can come up in your average class.

It is also a help to the actual teacher when someone can give a quick answer to those odd, even off-topic questions that come up, so the teacher can get back on topic. You culprits know who you are….

I should also add that this is a new routine for me, and is slowly evolving as I use it. It also varies a bit depending on the genre of the biblical book we are studying. For Old Testament history I do more historical study and less textual work because my Hebrew and my resources aren’t up to it. For the Gospels I do more synoptic comparison and non-canonicals research, because that‘s a scholarly trend right now and I am fascinated by the agrapha, even if Craig Evans dismisses it.

So as they say, this is where I am at right now, in regard to Sunday School preparation. Here are the steps as I can best outline them:

1. Read the lesson passage in the Learner book.

Of course, you’ve got to read the text first. This can involve different amounts of material. The lesson starts off with a title and then two sets of verses:

A) Background passage: the length of material assumed necessary to grasp the context of the lesson.

B) Lesson passages: those verses actually studied and commented upon in the Learner book.

Sometimes the background passage and the lesson passages are the same. Sometimes the background is several chapters and the lesson passages are the highlight verses within the background passage. My strong suspicion is most folk only read the lesson passages, and even that only in the translations provided in the Sunday School book.

Yes, I said translations. The Explore The Bible Learner Guide provides the lesson passages in side by side renderings from the Holman Christian Standard Bible and of course, the King James Version. This selection leads us to my next step.

2. Check HCSB and KJV for obvious differences.

I love parallel Bibles. But they can confuse someone who does not understand the background of translations. Not only do different Bibles read differently because of different translation philosophies (mirroring the original text versus mirroring contemporary speech of the translation‘s day, to grossly simplify) but also because translations are based upon different “original” texts. Speaking strictly of the New Testament, Older Roman Catholic Bibles were based upon the Latin Vulgate, which varied in places from the King James Bible, based upon Erasmus’ Greek New Testament. And both vary again from Bibles published in the last 130 years, when discoveries of massive numbers of Greek, Latin, Coptic, Syriac and many more language new testament manuscripts have led scholars to create several “standard” Greek New Testaments, which has further led to each new translation’s translator(s) being forced to decide in numerous places which Greek wording seems more original to them.

All of which is to say that the HCSB and the KJV do not always agree, and not only because centuries separate the vocabularies of the two. The venerable old KJV is based on Greek manuscripts from the Middle Ages, which tend to be more verbose in fear of leaving something good out. The HCSB is based on the current scholarly Greek New Testament, which tends to follow the earliest well-produced manuscripts, whose scribes had not yet added wordings to make things clearer or more reverent, and thus tends to be shorter.

So, after reading the HCSB and the KJV, I do a comparison of their wording, and I take a pen and circle the differences I see, either in vocabulary or in text. That gives me a series of verses which I can then use as a guide for the next step.

3. Check NET diglot for textual notes.

This is the first step where level of education rears its head. I personally have what might be described as “word study Greek.” I can read Greek letters and I know a lot of root words in the vocabulary. Thus I can use certain tools an English-only reader cannot. There are tools for the Greek-impaired to do these sort of things, too, though.

For those with Greek or without, the NET Bible First Edition is a great help, if you don’t let yourself be intimidated. With over 60,000 notes (compared to many study Bibles’ 20,000 notes) the NET is either a study Bible on steroids or an emaciated commentary. Besides the inevitable complaints about its translation philosophy, the NET’s chief strength is its greatest weakness: it has notes for every level of user. Simple definitions of terms sit alongside lengthy discussions of textual critical issues using manuscript numbers and Greek wording. Transliterations are provided as well as notes with “literal” translations of phrases, though.

My preferred edition of the NET when dealing with the New Testament (and we Christians usually are) is the NET Diglot. That is, a parallel Bible with the Nestle-Aland 27th (NA27) edition of the Greek New Testament combined with the NET English translation and notes. Why? Because I am a hopeless New Testament textual criticism geek. Reading the New Testament in Greek for most will simply confirm how careful most translations are to get things as right as they can. And because inevitably translators use

the same reference books and read each other’s translations, a good parallel English New Testament will reveal strong similarity in most Bible passages. But when they do differ, there is no better one stop resource than the NET diglot, which combines the mini-encyclopedia of the NET with the second mini-encyclopedia of the NA27, which endlessly footnotes even minor variations in the wording of NA27’s Greek text by citing which important manuscripts differ from the NA27, then which ones agree with NA27, then which important previous editions of the Greek New Testament agree or disagree with NA27. All of this together with an appendix citing the approximate age of the important manuscripts and what text of which New Testament books they contain.

All this can make for information overload, and the chief complaint against NA27 is that it requires one to learn practically another language in the form of NA27’s symbols and abbreviations to truly use it well. There are two solutions to this:

a) NET Diglot comes with a little foldout containing the witnesses, signs and abbreviations used in the NA27 that will be constantly in readers’ hand.

b) NET footnotes on the opposite page contain English sentences stating as simply as possible much the same information as abbreviated in the NA27 footnotes.

So, having found out what the NET Diglot says about the differences between HCSB and KJV, I will usually circle or underline the variation in the Learner book, draw a line out to the margin of the page, and write out a transliteration of the Greek, together with the earliest manuscript or two supporting each variation with rough date.

At this point I will also be mulling over other things I have learned from the footnotes on the NET side of the diglot, which I will have noticed mentions literal translations, other text critical issues, or even translation issues. But now it is time to go back to the Learner Guide for the next step.

4. Read the passage overview in lesson book, noting where the author keys on words, provides definitions or parallel verses.

In other words, grill the author on the assertions he makes. If he defines a word, I’ll circle it, find the Greek term in the diglot, see how NET translates it, and if I’m at all suspicious of the English term, walk over to my book case and pull out my copy of The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology: Abridged Edition

Key words and parallel verses require more work and more tools. I will cross check the English against the Greek so I get one term, then for the key words simply see how often they are repeated in the Greek text. I do this with E-sword, the excellent FREE (mostly) Bible software. By simply highlighting the Greek word and clicking, I can run a search on the word in the current book or the New Testament. With a copy, a switch to the LXX, and a paste, I can further search for the word in the Old Testament. Even with my poor Greek, I can flip through English versions in E-sword and get a sense of the range of meaning for the word, and very often discover parallels to my New Testament text.

If this doesn’t satisfy me (and by now you realize I’m not easily satisfied) I can hit the books again. Specifically Goodrick, Kohlenberger and Swanson’s The Exhaustive Concordance to the Greek New Testament

This is the point scratch paper comes in handy. Among these many verses I will make note of the parallels quoted in the Learner book and my search I find significant. That leads me to the next step.

5. Significant parallels I paste together and print out in Greek and English, particularly where outright quotes from LXX or a usage determining a discussed word meaning occurs.

Simply put, I’ll cross check my scratch list, pick the most important, then make a file of the New Testament and Old Testament parallels in Greek and English which I resize as small as readable, then print up double-sided to be folded up and stuffed in my now bulging Leaner Guide, along with that possible article from NIDNTT.

6. I print out Robertson's Word Pictures in the New Testament

Because I need all the Greek help I can get, and because, to borrow from Rick Brannan, A.T. Robertson was a stud. Or to be more technical, because Robertson wrote a still highly regarded Greek grammar and he published Word Pictures after the papyri boom of the 1900s which changed forever our understanding of New Testament Greek.

7. I read Barclay's Daily Study Bible

Yes, it is only here I get to the commentaries proper. Unless I am cheating a bit. Which lately I am. I bought a copy of Thomas Schreiner’s 1 Peter, 2 Peter, and Jude in the NAC series)

Anyway, by this time I know enough about the lesson passage that I can run through the commentaries pretty quickly. Mostly I am looking for different material: cultural background, classical references, historical information. Besides the cultural, most of this will not likely come up in Sunday School. I make notes on my scratch paper, which is at least two sides of paper or two sheets by now.

8. I run off the appropriate page(s) from Bruce Metzger’s Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament

Because I’m a textual criticism geek, but also because Metzger sometimes has odd little sidelines and Omanson discusses how segmentation can affect translation. And of course, Metzger is still THE Man.

9. I sit down with all these pages and put short notes in my Learner book.

Basically, I select what I find important, interesting, and/or easy to write briefly and write it up in the book where I will easily remember it. That usually includes Greek transliteration of key words or confusing terms in KJV along with definitions, notations of words not in the Greek supplied for English clarity, parallel verse notations, occasional flow charts of the author’s argument, and almost always questions about multiple interpretations of a phrase or verse. That’s a fair amount of black ink

scribbled in the book, along with that now sizeable sheaf of printouts in the center of the Learner Guide.

10. After a break of a day or two, I go back and review what I've compiled.

Like preparing for a test, I check to see what I remember and what I need to review. I will also likely scratch out some notes and add some new ones, because I see things more clearly after a break.

11. I go to Sunday School and never use ninety percent of what I've learned.

Because I’m not the teacher, and because I want to help my fellow members learn, not confuse them.

12. I come home from Church and after lunch start the process over again for the next week's Sunday School lesson.

Because I really enjoy all this study.

Thanks Chuck for sharing all this. I've heard it said (and I agree) that sincere study of the scriptures is just as valid of a style of worship as any other. I know many of This Lamp readers will relate to Chuck's enthusiasm for understanding the scriptures even if they have slightly different steps of their own. I can relate to Chuck because I've always said that I feel most alive when learning, and I feel most in God's will when I am teaching what I've learned.

Chuck Grantham can be reached at chuckgrantham@cableone.net, and I know he would appreciate your feedback in the comments.

Worthy of Note 3/19/2007

1. The new TNIV Truth blog. Ben Irwin, former employee of Zondervan, has a must-read post: "TNIV: Basic Idea or Details of Meaning?"

2. Kevin Sam's thoughts on the New Living Translation.

3. Gary at "A Friend of Christ" blog has begun to rethink his position on the TNIV.

4. ElShaddai Edwards examines Genesis 1:28 in the NLTse, HCSB, TNIV, and REB.

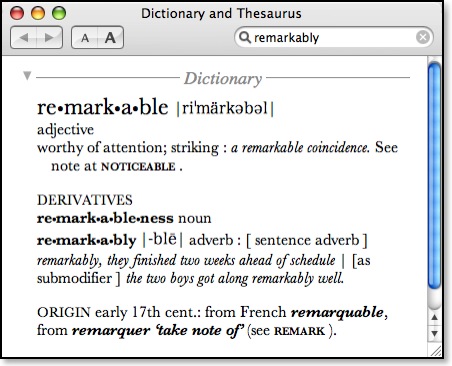

Remarkably and Wonderfully Made

“For it was You who created my inward parts;

You knit me together in my mother’s womb.”

(Psalm 139:13 HCSB)

Our passage of study in Sunday School tomorrow is Psalm 139. As I was reading through the leader's guide to the curriculum tonight, a couple of paragraphs related to v. 13 stood out:

The second line in this verse is an example of a common characteristic of Hebrew poetry. The second line repeats the first line, but it does so by the use of synonyms. Hence knit me together is a synonym for created in the previous line. In light of the complexity of the human body the verb knit me together generates a mental picture that fits the context as well. Inside the womb, God wove tissue, bone, and sinew to form a living being.

The average adult body consists of approximately 650 muscles, 50,000 miles of blood vessels, and 206 bones. About 20 square feet of skin tissue covers these components in males and about 17 square feet is required in females. A baby at birth is even more complex than an adult. The infant has 300 bones. During childhood 94 of these fuse together.

Contemplating such complexities of the human body and God's awesome creative ability makes one truly exclaim with the psalmist the next verse:

“I will praise You,

because I have been remarkably and wonderfully made.

Your works are wonderful,

and I know |this| very well.”

(Psalm 139:14 HCSB)

This Is Why

I'll admit that at least as far as five or six years ago from my own study, I realized that the NASB, while technically literal, was somewhat lacking in some places--especially in Old Testament poetic sections--when it came to bridging the language gap between the biblical culture and context and ours. Literal translations have difficulty communicating metaphors and symbolic imagery. It's easy for the meaning to become lost. But I continued teaching from the NASB nonetheless. Then my confidence in the NASB was completely shattered in early 2005 when in the middle of a half-year study on Romans I was teaching at my church, I realized that the translation itself was getting in the way. This was a study separate from any curriculum. It was all me. The problem arose, however, when I found I was having to explain the English of the NASB in order to explain the meaning of the biblical text. That was clearly an unnecessary step. Communication was impeded by the translation itself. Did that make sense? Translations are supposed to be bridges, but what if the bridges themselves are in disrepair?

I knew that there were two primary philosophies of translation: formal equivalent (word-for-word) and dynamic equivalent (thought-for-thought or meaning-driven). At the very least I knew that I needed to move a bit further down the spectrum toward dynamic equivalence. But how far? After spending weeks considering various translations, I settled on the Holman Christian Standard Bible for my Sunday morning translation of choice. It was a good bridge as a translation between the two methods because it was literal when it could be literal, but dynamic when that didn't work quite as well. Plus, our Sunday School literature uses HCSB. So I was teaching from the translation used in my class' quarterly.

And now we're in Hebrews. And I'm using curriculum this time. But sometimes I don't like certain turns the curriculum makes. Today's frustration came from the curriculum writer's decision to leave out nearly half of the verses in ch. 7. Hebrews itself is a complicated book in my opinion which may explain why very few ever touch it outside of the eleventh chapter. In my understanding, the writer is developing a carefully crafted, but complicated argument of why Jesus is better than the angels, the prophets, Moses, the High Priest, the Levitical priesthood, etc., and there's no possible way to go back to an earlier form of faith pre-Messiah.. I suppose that the curriculum writer chose to simplify things for the readers by leaving out a large section of the chapter. But in my opinion, he short-circuited the biblical author's argument in the process.

So I saw my task this morning as one of making my class understand the writer of Hebrews' argument--without leaving out any verses--and in the end creating room for some kind of practical application they could leave with. It's easy to get bogged down in Hebrews and forget that last part. I wrote in this blog a few weeks back that the KJV rendering of Hebrews seems unintelligible in places. I believe this is probably due to the difficulty of the Greek. And while the HCSB was good, and certainly better than the KJV or even the NASB would have been, I was still having some doubts, even as late as this morning about whether I was using a translation that made Heb 7 crystal clear. Somehow between the translation, my teaching ability, and the power of God's Holy Spirit, I wanted my class to have a clear understanding of Hebrews ch. 7 by the time they left the study. And so at the last minute--right around 8:30, a half hour before we had to be at church--I switched translations. I grabbed my TNIV, a translation that I although I have promoted on this blog, I have only used in public for devotional purposes.

Don't tell my pastor, but in the middle of his sermon on Romans 6, I stole over to Hebrews 7 and familiarized myself with the TNIV text. I had looked at it during my preparation, but I had not originally been planning to teach from it. Then when we got to our class after the sermon I began walking my class (the best metaphor for it) through the end of Hebrews 6 and into the seventh chapter. The fact that I was using the TNIV didn't really become a factor until the end when I read the last passage of our study, Heb 7:20-28, myself because we were short on time. Now, it was probably because of momentum built from our journey through the text thus far (I believe they were understanding), but as I read from the TNIV, I felt like they were extremely engaged and fully understanding the words--which in the latter part of ch. 7 do serve as a powerful summation and application of the writer's arguments.

I actually heard amens and other verbal affirmations while I was merely reading the biblical text (with enthusiasm, mind you). There was an excitement in the room simply as I read the Scripture passage. Amazing--I don't know if I've ever had so many people in tune before with what was being read from the Bible, with only minimal comment from me. Now, while there are quite a few factors involved, I have to think that the translation itself--the TNIV--was a primary contribution to my class' understanding of Hebrews today.“And it was not without an oath! Others became priests without any oath, but he became a priest with an oath when God said to him:

“The Lord has sworn

and will not change his mind:

‘You are a priest forever.’”

Because of this oath, Jesus has become the guarantor of a better covenant.

Now there have been many of those priests, since death prevented them from continuing in office; but because Jesus lives forever, he has a permanent priesthood. Therefore he is able to save completely those who come to God through him, because he always lives to intercede for them.

Such a high priest truly meets our need—one who is holy, blameless, pure, set apart from sinners, exalted above the heavens. Unlike the other high priests, he does not need to offer sacrifices day after day, first for his own sins, and then for the sins of the people. He sacrificed for their sins once for all when he offered himself. For the law appoints as high priests men in all their weakness; but the oath, which came after the law, appointed the Son, who has been made perfect forever.”

(Heb 7:20-28, TNIV)

And I didn't plan to write about any of this, although it's been on my mind and heart all day. Then I read Richard Rhodes' post tonight on Better Bible Blogs, titled "What's the Joke?" In this wonderful blog entry, he skillfully demonstrates why literal word-for-word translation is not always the best means for communicating meaning from one culture to another. He does this merely by trying to translate a newspaper cartoon from German to English. The entire article is well worth your time and demonstrates succinctly what's taken me a few years to learn through my experience teaching: literalness ≠ good translation.

Again, please read his entire post, but I must at least repeat his final thoughts here:

Our long use of translations that only approximate the meaning of the Greek (or Hebrew) has dulled our senses. It’s only in live cross-linguistic situations that we are confronted with the fact that language is regularly used with a precision we fail to appreciate from the inside. And it’s that precision that gets washed away in most Bible translations by our preference for literalness. Ironically, that preference all but guarantees that we will get it wrong.

If I think I'm teaching God's Word, but my students can't understand me, ultimately it's my fault. I have not actually taught; I've merely performed, and I've performed poorly at that. A Bible translation is like a tool. Certain jobs demand different tools, and some tools are right for the job while others aren't. I still recommend students of the Bible study in parallel with both formal and dynamic translations. But perhaps, for me, it's again time to go a little bit further down that translation spectrum regarding the

Hebrews 4:8 in the KJV

The Lifeway Explore the Bible curriculum uses two translations as its base, the HCSB and the KJV and normally reproduces the verses side by side. Any quick look at Heb 4:8 in these two translations immediately demonstrates a problem:

| HEBREWS 4:8 | |

|---|---|

HCSB |

KJV |

| For if Joshua had given them rest, He would not have spoken later about another day. | For if Jesus had given them rest, then would he not afterward have spoken of another day. |

Obviously, there's going to be a big difference in the meaning of the passage based on whether the writer is speaking of Joshua or Jesus. What?! You don't remember the Old Testament story about Jesus leading the Israelites into the Promised Land?

For sake of comparison, here are a few other translations of the verse:

"For if Joshua had given them rest, God would not have spoken later about another day." (NIV/TNIV)

"Now if Joshua had succeeded in giving them this rest, God would not have spoken about another day of rest still to come." (NLT)

"For if Joshua had given them rest, He would not have spoken of another day after that." (NASB)

"For if Joshua had given them rest, God would not speak later about another day." (NRSV)

"For if Joshua had given them rest, God* would not have spoken of another day later on." (ESV)

Obviously, the majority consensus is for Joshua, not Jesus. And it certainly makes sense because the context of the writer's argument is an analogy that he's drawing from the Israelite's entrance into the Promised Land. So why the difference in the KJV?

Well, part of the problem with the King James Version is that in the New Testament the translators chose to transliterate the Greek versions of the names of Old Testament characters rather than matching up the spellings with what was used in the KJV Old Testament. So in Matt 24:37, Noah is represented as "Noe," Elijah becomes "Elias" in Matt 11:14, Isaiah becomes "Esaias" in Matt 3:3 and so on. Some of these the reader will catch, but such inconsistency between the testaments can and certainly has created confusion and even misinterpretation in the past. [Consider for example, the blunder made by Mormon "prophet" Joseph Smith in Doctrine & Covenants 76:100, where he writes, "These are they who say they are some of one and some of another—some of Christ and some of John, and some of Moses, and some of Elias, and some of Esaias, and some of Isaiah, and some of Enoch...." It hardly seems fitting for a so-called "prophet" to make such an error that would become part of their sacred and "inspired" writings, wouldn't you think?]

That brings us to Jesus and Joshua. The two have the same name. Jesus is the Greek form (Ἰησοῦς/Iesous) and Joshua is the Hebrew form (יהושע/Yehoshua) of the same name. So, technically, the KJV translators were being consistent in their method of keeping the Greek form of the names of the Old Testament characters when it came to Heb 4:8. But surely anyone can see the confusion that such a practice causes. The same kind of misreading is caused in Acts 7:45 which again reads "Jesus," when the context is obviously referring to Joshua.

Every major modern translation today has gone to keeping the names consistent between the testaments. And the TNIV has gone a step further in that the translators have chosen to update the spellings of certain names to bring them closer to their Hebrew originals. A chart of such spelling changes is in the back of every TNIV Bible.

Hebrews 4:8 is a perfect example of why I never recommend the KJV as a primary translation for serious study. Even the student who can plow through the Elizabethan English fairly well has a strong possibility of misinterpreting a verse like Heb 4:8 or Acts 7:45. Further, I've noted since beginning our study in Hebrews, as I've been translating some of it, that the Greek is more difficult in this book than most other places in the New Testament. And that is reflected in the KJV rendering of many of the passages in Hebrews which come across as nearly unintelligible (see, for instance Heb 3:16-18 in the KJV).

I suppose it would be controversial for some to hear that the KJV can lead to misunderstandings and misinterpretations of the text in a verse like Heb 4:13 or Acts 7:45. Maybe that's why the editors at Lifeway decided to simply leave that verse out of the study. But v. 8 is an essential part of the writer's argument. Plus, for the one or two KJV users in my class, bringing up the issue was a way to gently encourage them to use a newer translation. Therefore, we covered v. 8, and everyone understood that the reference was to Joshua.

The Problem with Capitalized Pronouns

And isn't it downright odd to use capitalized pronouns in the words of Jesus' enemies such as in John 19:6, "This man is not from God, because He does not keep the Sabbath" (NASB)?

On Sunday mornings, I usually teach from the Holman Christian Standard Bible which also capitalizes pronouns, but this has often caused problems such as the issue I described when I wrote my review on the HCSB:

Another problem with the HCSB is that the translators chose to capitalize pronouns referring to deity. In most passages, the pronouns are pretty clear, but not in all. A case in point is Micah 7:14 which was part of a larger passage covered in the Lifeway Explore the Bible Curriculum for May 28. The HCSB capitalizes the pronouns, rendering the text, "Shepherd Your people with Your staff, the flock that is Your possession." Thus, the way the pronouns are capitalized, it would lead one to believe that this is a prayer to God from the prophet Micah. But is this the case? Ironically, in the actual SBC curriculum, the writer took the passage much differently suggesting that this was God's commands to earthly kings. Therefore, the curriculum writer disagreed with the HCSB, both of which are from the same publisher. I agree with the writer, but the translators' decision to use capitalized pronouns creates unnecessary problems.

My personal opinion is that all translations should abandon the practice of capital letters for pronouns referring to deity. In doing so, they remain faithful to the original text and they prevent unnecessary confusion.

Be sure to read Jeremy's post.

Who's "This Guy"?

Previously, I blogged about the HCSB's use of "slacker" in certain verses. While some thought this too informal, or perhaps might even date the HCSB, I found it to be the perfect alternative to sluggard which is used in most translations. Further, since the word "slacker" has been in use for a century and is probably here to stay, I didn't feel like the HCSB's use of the word would date it as a translation at all. And of course, it also gives me the excuse to use the word "slacker" in public contexts now and then. I really like that.