Industry Insider: Bible Translation Rankings Are Faulty

Well despite the fact that we don't get the full picture, the reality of the system in place for CBA stores is even worse.

This morning, I received an email from an industry insider who asked to remain anonymous, but agreed to let me summarize/paraphrase the content of the email.

According to this person--who has been tracking Bible sales for four years--ECPA/STATS figures, which are reported by the CBA, has been having problems with their Bible market share numbers for quite some time. A number of publishers, including the "market leader," have complained for a while now that the numbers simply don't add up to their own calculations--something my emailer confirmed since this person has been tracking these numbers for some time, too.

And my emailer also told me that even if the numbers were correct, the rankings would still be deceptive because two of the Bible market's bestsellers, the Nelson Million Bible Challenge [$1] and the ESV Outreach NT [50¢] are sold primarily based on price and not translation choice. Bibles such as these serve to skew the rankings based on the way the current system works. Evidently, if these two products were eliminated from the stats OR if rankings were based in pure dollar sells, the top ten list would look quite different.

This same person told me that a better system of ranking is coming soon. Stay tuned because I'll let you know more about it as soon as I'm able.

Bible Translation Awareness Survey Results

This was actually the third week I'd carried the survey with me as I was waiting for an ideal representation of our roll to respond. Yesterday we had 35 class members in attendance, no visitors, and about 10 of our regular attenders were absent. I handed out 35 surveys, but only got back 26. We are in a Southern Baptist church, and our class uses Southern Baptist curriculum.

Here is how I introduced the survey on the form I handed out to everyone:

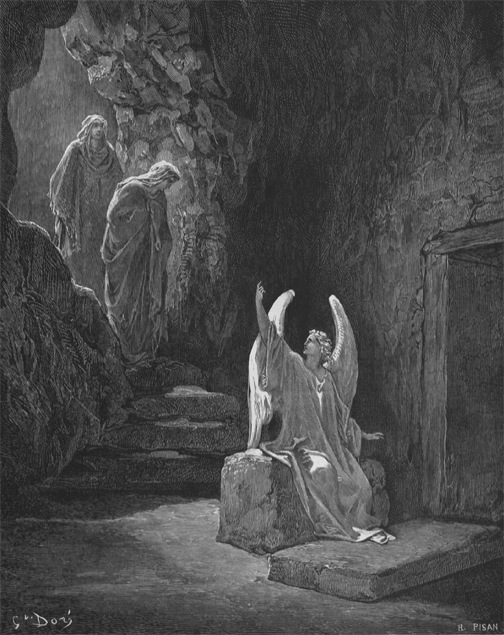

Augustine said that it was profitable to study the Bible with parallel translations. On any given Sunday morning, there are multiple translations of the Bible represented in our Quest Bible Study—and that’s a good thing! This survey will help your teacher in his preparation by knowing what translations are in use in the class by what percentages of learners. Also, it will help him gauge your awareness of translations. Please answer the questions as honestly as possible.

Here are the results of the survey:

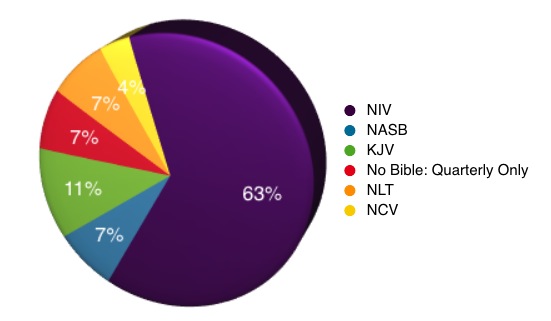

Q1. What translation of the Bible are you using this morning? [I had a list of translations to choose from including an option for other and an option for the Sunday School quarterly instead of a Bible]

- 2 said they didn't bring a Bible, but were using a quarterly. This means they had access to the HCSB and KJV.

- 17 members were using the NIV. Our pastor preaches from the NIV, and of course, the NIV is the most popular translation in the US, so it no surprise that almost 2/3 of the class were using this version.

- 3 were using the KJV.

- 2 were using the NASB.

- 2 were using the NLT (I didn't specify which edition in the survey).

- We had one person respond saying he was using the NCV. I know of one other person in the class who uses the NCV, but he wasn't there today.

Q2. Did you know what translation you were using, or did you have to look at your Bible to double-check? [This was my awareness test. Assuming they answered truthfully, more folks are aware of their translation than what I would have imagined.]

Twenty-two answered "I knew"; three answered "I had to double-check."

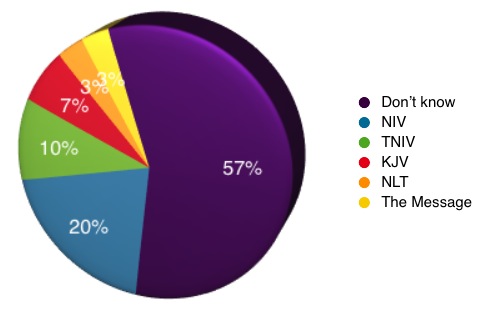

Q3. What translation of the Bible does your teacher use? Don't guess. If you don't know, write, "I don't know."

- 15 respondents said they didn't know what translation I was using.

- 6 said that I was using the NIV.

- 3 said I was using the TNIV.

- 2 guessed I was using the KJV!

- 1 suggested the NLT

- 1 thought I was using the Message.

The correct answer is that I use the TNIV. When we started the class last March with less than a dozen members, I was teaching from the HCSB because it is the primary translation in the Sunday School quarterly. However, last fall while teaching through Hebrews, I switched to the TNIV, so I've been using that for about six months. I did use the Message one time a few weeks ago to read through an extended passage in Esther. I mentioned that I was reading from that version, and that name must've stuck with someone. I have never and would never use the KJV to teach a regular Sunday School class. I've used the KJV occasionally in other venues, especially when speaking to senior adults.

I mention now and then that I am reading from the TNIV, but I don't make a big deal out of it.

Q4. When you study your Bible at home, do you ever use another translation? If so, list what you would consider your primary translation, and what you would consider any secondary translation(s). If you never study your Bible at home, simply write, “I never study my Bible at home” (this survey IS anonymous!).

One person admitted that no Bible study ever takes place at home. Here are the rest of the results:

Primary translations:

- NIV: 17

- NLT: 2

- KJV: 2

- NASB: 1

Secondary translations:

- KJV: 6

- NIV: 2

- NASB: 2

- HCSB 1

- NCV: 1

- NKJV: 1

- Amplified: 1

- Phillips NT: 1

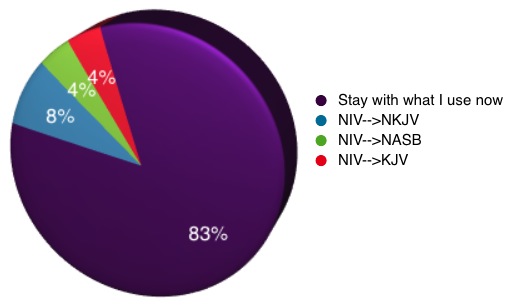

Q5. If you lost your main Bible and had to buy a new one this week, would you buy the same translation you checked in question #1 or would you get a different one? If you would get a different one, what would it be?

- 20 of those surveyed said that if they had to replace their Bibles, they would stick with the translation they currently use.

- Two said they would switch from the NIV to the NKJV.

- One indicated a switch from the NIV to the NASB.

- One said a switch from the NIV to KJV would take place.

Again, for anyone else, these results are simply anecdotal. But the majority of my class using the NIV reflects national trends. Further, if there're any broader implications to be drawn, question #5 would indicate that people don't change translations very often or very easily. Most importantly, my choice to teach from the TNIV is a good one with most of the class' members reading from the NIV. They can follow easily enough when I read from the TNIV as there is much continuity from their version, but at the same time the TNIV offers a more accurate and up-to-date option over the NIV.

One last thought... to my knowledge, there's been no recent class at our church about the history of English translations and the differences between them. I wonder if any of the questions would be answered differently if such a discussion took place prior to such a survey?

Link: Bible Translation Awareness Survey

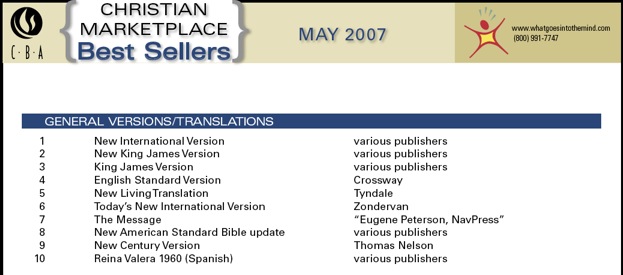

May CBA Top Selling Bible Translation Lists Posted

Of note: the NIV is back on top after a 3rd place showing below the KJV and NKJV last month. The ESV is now at #4, pushing the NLT down to #5. The TNIV is up to #6 from #10 last month. The HCSB remains nowhere to be seen for yet another month.

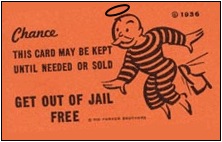

Bible Memory Pays Off: Crook Gets Out of Jail Free

Ohio Credit-Card Defendant Released on Bond After Reciting 23rd Psalm

Thursday, April 26, 2007

CINCINNATI — A man arrested Wednesday in Cincinnati got a break from a judge after passing a Bible quiz.

Eric Hine allegedly used a stolen credit card to try to buy things at a drugstore, authorities said.

When he appeared in court Wednesday morning to face a charge of receiving stolen property, his attorney described Hine as a church-goer in hopes that the judge would set a low bond.

Hamilton County Municipal Court Judge John Burlew was skeptical and asked Hine to recite the 23rd Psalm.

Hine did: all six verses. Some in the courtroom applauded.

Burlew was satisfied and released Hine on a $10,000 appearance bond, meaning he'll have to pay that amount if he doesn't show up for his next court date.

Of course, this should be even greater incentive to all those AWANA kids to memorize their verses.

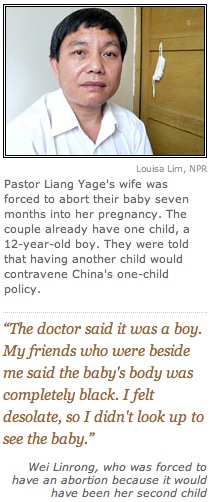

Forced Chinese Abortions Back on the Rise

Morning Edition, April 23, 2007 · During the past week, dozens of women in southwest China have been forced to have abortions even as late as nine months into the pregnancy, according to evidence uncovered by NPR.

China's strict family planning laws permit urban married couples to have only one child each, but in some of the recent cases — in Guangxi Province — women say they were forced to abort what would have been their first child because they were unmarried. The forced abortions are all the more shocking because family planning laws have generally been relaxed in China, with many families having two children.

Liang Yage and his wife Wei Linrong had one child and believed that — like many other couples — they could pay a fine and keep their second baby. Wei was 7 months pregnant when 10 family planning officials visited her at home on April 16.

Liang describes how they told her that she would have to have an abortion, "You don't have any more room for maneuver," he says they told her. "If you don't go [to the hospital], we'll carry you." The couple was then driven to Youjiang district maternity hospital in Baise city.

"I was scared," Wei told NPR. "The hospital was full of women who'd been brought in forcibly. There wasn't a single spare bed. The family planning people said forced abortions and forced sterilizations were both being carried out. We saw women being pulled in one by one."

Read the full story here. It only gets worse.

There's great irony to this story. Kathy and I sent our adoption dossier to China earlier this year. Sometime over the next two or three weeks, all of our information will have been translated and logged into the Chinese adoption database. Then we will wait somewhere close to a year and a half (the current average is 17 mos.) to receive our daughter because the demand for Chinese adoption is so very great.

TNIV Truth: Read through the TNIV in 90 Days

GUEST REVIEW: The New Oxford Annotated Study Bible (3rd Edition)

Below is a guest review from This Lamp reader, "Larry."

The Benchmark: the New Oxford Annotated Study Bible (3rd Augmented Edition)

A recent post by Rick described the debate in Muscogee County, Georgia over which translation to use in a public high school Bible class. The superintendent of the school was described as leaning towards the New King James Version – an odd choice for a secular setting, an odd choice for a setting desiring the latest scholarship, an odd choice for a high school class. But imagine that you were designing a college course to be taught in a secular school on the Bible. Which version would you use?

The New Oxford Annotated Study Bible (NOAB) aims to fulfill this role by being (as declared on the cover) an “ecumenical study Bible.” (An unfortunately ambiguous phrase – the Bible does not advocate ecumenicism, but rather is meant to be used equally by the various Protestant, Catholic, other Christian, and even in Hebrew Scriptures, by Jewish readers.) It includes not only annotations and book introductions, but a variety of helps (brief essays, maps, and glossary) appropriate to an academic audience. Although it is printed on bible paper and has rather better binding than a typical textbook, this book otherwise screams I am a college textbook in one’s hand. And as such, it was wildly successful, quickly becoming the standard text for academic Bible classes. And it became something of a standard reference for those interested in academic-style self study.

But does the NOAB deserve this praise? This pioneer has come under attack from all directions: there are a variety of new, more heavily annotated study Bibles available; it has been attacked for a leftward turn in its most recent editions; and it no longer seem as ubiquitous as it once was. What has happened to the NOAB? This review will explore the most recent edition, the Third Augmented, of the New Oxford Annotated Bible.

Acronyms

This is the second of my reviews of academic (and a few faith-oriented) study Bibles. Here is a brief list of versions I plan to cover together with acronyms I use.

JSB: Jewish Study Bible (Oxford 2004) [NJPS]

NOAB: New Oxford Annotated Study Bible (3rd Augmented Edition) (Oxford 2007) [NRSV]

NISB: New Interpreter’s Study Bible (Abingdon 2003) [NRSV]

HSB: HarperCollins Study Bible (2nd edition) (Harper San Francisco 2006) [NRSV]

CSB: Catholic Study Bible (2nd edition) (Oxford 2006) [NAB]

OSB: Oxford Study Bible (Oxford 1992) [REB]

WSP: Writings of St. Paul (2nd edition) (Norton 2007) [TNIV]

ECR: Early Christian Reader (Hendrickson 2004) [NRSV]

TSB: TNIV Study Bible (Zondervan 2006) [TNIV]

OSBNT: Orthodox Study Bible: New Testament and Psalms (Conciliar Press Edition) (Conciliar Press 1997) [NKJV]

Readers may want to look back at my first review in which I discussed the framework for analysis and specifically mentioned that I find the terms “liberal” and “conservative” unhelpful and ambiguous when evaluating study Bibles.

An overview of the NOAB

The New Oxford Annotated Study Bible, 3rd Augmented Edition

Michael Coogan, editor

Marc Z. Brettler, Carol A. Newsom, Pheme Perkins, Associate Editors

Translation: New Revised Standard Version

Hebrew Scriptures: yes

Deuterocanon: yes

Christian Scriptures: yes

Current Amazon price: $28.35

xxvii + 1375 Hebrew Bible + 383 Apocrypha +640 New Testament & extras + 2181 + 32 map pages

Extras:

Medium length introduction to books and major sections

60 black and white diagrams and maps

32 page color map section, with 14 large color maps.

Listing of biblical canons

Index and map index

Hebrew calendar discussion

Timeline (Egypt/Israel/Syria-Palestine/Mesopotamia)

Chronology of rulers in Egypt/Assyria/Syria/Babylonia/Persia/Roman Empire/Israel

Table of weights and measures

Listing of parallel texts (synoptic passages) in the Hebrew Scriptures, Apocrypha, and New Testament

Glossary of terms (15 pages)

Bibliography of translations of primary sources

Concordance (66 pages)

72 pages of additional essays

The editors of the volume are

- Michael Coogan (Stonehill Coll.) a former faculty member at Harvard, Michael Coogan for many years served as the director of the Semitic Museum’s publication program. He still maintains a relationship with Harvard Museum. He is well known as a biblical archaeologist. He was involved as a critical reviewer of both the 1991 and 1999 editions of the Catholic New American Bible (whose translation team includes some Protestant scholars.)

- Marc Zvi Brettler (Brandeis) who holds a named chair and chairs the Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies. He was co-editor of the JSB, the author of a major textbook on Biblical Hebrew, and is well known for his teaching, which is reflected in a very nice volume he wrote called How to Read the Bible. He is a strong advocate of what he calls “Jewish sensitive” readings of the Bible.

- Carol Newsom (Emory) a faculty member at the Candler School of Theology, the author of several commentaries on Job, and co-editor of the Women’s Bible Commentary. She also actively participates in the Episcopalian Church USA.

- Pheme Perkins (Boston Coll.) is best known for her work in early Christianity. She is a former president of the Catholic Bible Association and is also active in the Society for Biblical Literature.

Notes on the NRSV translation

The NOAB, like many leading academic study Bibles (HSB, NISB, ECR) uses the NRSV translation – a translation that is probably familiar to most of the readers of this blog. The NRSV is popular because it is a moderately formal translation, has the widest degree of acceptability among different denominations, is derived from the dominant strand of English Bible translations (the Tyndale/KJV tradition), and includes the Catholic and Orthodox deuterocanon/apocrypha. The translation is strikingly different in how it treats the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures – the Hebrew Scriptures are translated into more formal language than the Christian Scriptures, reflecting their different source material. The translators explain,

The NRSV also attempts, particularly in the Christian portions, to use inclusive language when context dictates that was the original meaning in the Greek. The translators explain,“Another aspect of style will be detected by readers who compare the more stately English rendering of the Old Testament with the less formal rendering adopted for the New Testament. For example, the traditional distinction between shall and will in English has been retained in the Old Testament as appropriate in rendering a document that embodies what may be termed the classic form of Hebrew, while in the New Testament the abandonment of such distinctions in the usage of the future tense in English reflects the more colloquial nature of the koine Greek used by most New Testament authors except when they are quoting the Old Testament.”

“Paraphrastic renderings have been adopted only sparingly, and then chiefly to compensate for a deficiency in the English language—the lack of a common gender third person singular pronoun. . . . The mandates from the Division [of Education and Ministry of the sponsoring organization, the National Council of Churches] specified that, in references to men and women, masculine-oriented language should be eliminated as far as this can be done without altering passages that reflect the historical situation of ancient patriarchal culture. As can be appreciated, more than once the Committee found that the several mandates stood in tension and even in conflict. The various concerns had to be balanced case by case in order to provide a faithful and acceptable rendering without using contrived English. Only very occasionally has the pronoun “he” or “him” been retained in passages where the reference may have been to a woman as well as to a man; for example, in several legal texts in Leviticus and Deuteronomy. In such instances of formal, legal language, the options of either putting the passage in the plural or of introducing additional nouns to avoid masculine pronouns in English seemed to the Committee to obscure the historic structure and literary character of the original. In the vast majority of cases, however, inclusiveness has been attained by simple rephrasing or by introducing plural forms when this does not distort the meaning of the passage. Of course, in narrative and in parable no attempt was made to generalize the sex of individual persons.”

In part because of this practice, a number of traditionalists prefer the use of the NRSV’s predecessor, the RSV – and Oxford has accordingly kept older editions of the New Oxford Annotated Bible based on the RSV in print.

Publication History of the NOAB

The NOAB is the latest in a long line of editions:

- 1962: The original Oxford Annotated Bible. Editors: Herbert May (Oberlin/Vanderbilt) and Bruce Metzger (Princeton). The version had the flavor of an “official annotated” version of the RSV – May and Metzger were the Chair and Vice-Chair of the RSV contributions were received from the chair of the RSV committee (Luther Weigle, Yale). Metzger was a leading Evangelical figure of his time.

- 1965: Revised edition of The Oxford Annotated Bible with Apocrypha. Editors: May and Metzger. This edition – not just the translation – but the annotated edition – received the imprimatur from Richard Cardinal Cushing of Boston.

- 1973: A major revision – (first edition of) The New Oxford Annotated Bible [editions appeared with and without Apocrypha.] Editors: May and Metzger. The contributors stayed the same as in the 1965 edition.

- 1977: The New Oxford Annotated Bible with Apocrypha, Augmented Edition. Editors: May and Metzger. This version included the newly translated 3 and 4 Maccabees and Psalm 151. This version received the approval of approval of Athenagoras (Greek Orthdox Archbishop of Thyateira and Great Britain, and a well-known supporter of the ecumenical movement). For many traditionalists, this was the high point of this series.

- 1991: The New Oxford Annotated Bible, Second Edition [editions appeared with and without Apocrypha.] Editors: Metzger and Roland Murphy (Duke). Roland Murphy, a Catholic priest, was well known for a variety of contributions to Biblical Studies. This edition featured a major change – it was based on the NRSV. The notes were moderately revised from the 1977 edition. A concordance was added. More controversially, the traditional two-column translation/one-column note format was abandoned for a two-column translation/two-column note format. And unfortunately, the various accents and pronunciation guides found for proper nouns in the earlier edition were abandoned, a feature that was not reappear in later editions.

- 2001: The New Oxford Annotated Bible, Third Edition [editions appeared with and without Apocrypha]. Editors: Coogan, Brettler, Newsom, Perkins. This was far beyond an ordinary revision of the Second Edition – it was a largely new rewrite. Almost every sentence was changed (except the underlying NRSV translation). A concordance was added, and the volume was larger than previous editions in every dimension. The typesetting was improved (and the format reverted to the older two-column translation/one-column note format was used). By this point, the edition was facing serious competition in the college market from the first edition of the HSB; and Oxford production team made a serious effort to fight back, and made the most easily readable version in the series to date (striking at the one of the HSB’s main weakness – its terrible physical design). Book introductions were much longer; annotations were longer (and featured more complete sentences); and far more contributors participated in the notes.

- 2007: The New Oxford Annotated Bible, Third Augmented Edition [so far only the edition with Apocrypha has appeared, although an edition without Apocrypha is promised.] Editors: Coogan, Brettler, Newsom, Perkins. This was a very minor update to the Third Edition; a few new black and white maps, charts and diagrams were included (put in at the end of books so the pagination remains the same), the book and section introductions had minor rewritings, and a useful glossary was added (which drew heavily on the glossary that had previously appeared in the JSB). Amusingly, the Oxford production team forgot to update the copyright page correctly (at least in the first printing.)

Review of the NOAB

As I begin to review the NOAB’s annotations think an academic study Bible is likely to see three major uses:

- As a classroom text (here my advice is least meaningful, since a student is likely to have to choose the study Bible chosen by the class instructor)

- For self-study As a reference source.

Now, I will reveal my punchline in advance: in this review and my next two reviews, I will rank the three NRSV study Bibles as follows

- Best for classroom use: NOAB

- Best for self-study: NISB

- Best for reference: HSB

Where did the annotations come from? The NOAB involves a much broader group of people involving much wider range of opinions than previous editions. The diversity can be seen from the range of different annotators – who reflect participants from a variety of theological backgrounds (Jewish, Mormon, Evangelical, Episcopalian, Mainline Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox) and a variety of different cultural backgrounds. This sort of diversity is in line with contemporary academic trends, and reflects the widely held belief that the academy – even in theological studies, should mirror society at large.

- Theodore Bergren (U. of Richmond): 2 Edras

- Mark Biddle (Baptist Th. Sem.): Jeremiah, Letter of Jeremiah, Baruch

- Joseph Blenkinsopp (Notre Dame): Isaiah

- M. Eugene Boring (Texas Christian U.): 1 Peter

- Sheila Briggs (USC): Galatians

- Mary Chilton Callaway (Fordham): 1 & 2 Maccabees

- David Carr (Union Th. Sem.): Genesis

- John Collins (Yale): 3 Maccabees

- Stephen Cook (Virginia Th. Sem.): Ezekiel

- Linda Day (editor, Catholic Biblical Quarterly): Judith

- F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp (Princeton): Lamentations, Song of Solomon

- Neil Elliott (adjunct faculty at United Th. Sem., Twin Cities, acquisition editor at Fortress Press): Romans

- Tamara Cohn Eskenazi (Hebrew Union Coll./Jewish Inst. Religion, Los Angeles): Ezra-Nehemiah, 1 Esdras

- Cain Hope Felder (Howard U.): James

- Obery Hendricks (New York Th. Sem.): John

- Richard Horsley (U. Mass., Boston): Mark, 1 Corinthians

- Cynthia Briggs Kittredge (Episcopal Th. Sem. Southwest): Hebrews

- Gary Knoppers (Penn. State): 1 & 2 Chronicles

- John Kselman (St. Patrick’s Sem.): Psalms, Psalm 151, Prayer of Manasseh

- Mary Joan Winn Leith (Stonehill Coll.): Ruth, Esther, Greek Esther, Jonah

- Amy-Jill Levine (Vanderbilt): Tobit, Daniel, Additions to Daniel

- Bernard Levinson (U. Minnesota): Deuteronomy

- Jennifer Maclean (Roanoke Coll.): Ephesians, Colossians

- Christopher Matthews (Weston Jesuit Sch. Th.): Acts

- Steven McKenzie (Rhodes Coll.): 1 & 2 Samuel

- Margaret Mitchell (U. Chicago): 1 & 2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon

- Gregory Mobley (Andover Newton Th. Sch.): Book of the Twelve (except Jonah)

- Carolyn Osiek (Texas Christian U.): Philippians

- Andrew Overman (Macalester Coll.): Matthew

- Pheme Perkins (Boston Coll.): 1, 2, 3 John

- Iain Provan (Regent Coll.): 1 & 2 King

- Jean-Pierre Ruiz (St. John’s U.): Revelation

- Judith Sanderson (Seattle U.): Exodus

- Leong Seow (Princeton): Job, Ecclesiastes

- Abraham Smith (): 1 & 2 Thessalonians

- Marion Soards (Louisville Presbyterian Th. Sem.): Luke

- Patrick Tiller (unaffiliated): 2 Peter, Jude

- Sze-kar Wan (Andover Newton Th. Sem.): 2 Corinthians

- Harold Washington (St. Paul Sch. Th.): Proverbs, Sirach

- Walter Wilson (Emory): Wisdom of Solomon, 4 Maccabees

- David Wright (Brandeis): Leviticus, Numbers

- Lawson Younger (Trinity Int’l U.): Joshua, Judges

While this list certainly contains many distinguished names, one cannot help but notice that the list of participants is not quite as distinguished on average as the participants in earlier editions. However, the annotations are far more detailed. As an example, consider the annotations in the NOAB of the first chapter Ezekiel (more exactly, Ezekiel 1:1-28a.) First, I’ll compare these with the first edition of the New Oxford, and then with some other study Bibles.

NRSV: [1] In the thirtieth year, in the fourth month, on the fifth day of the month, as I was among the exiles by the river Chebar, the heavens were opened, and I saw visions of God. [2] On the fifth day of the month (it was the fifth year of the exile of King Jehoiachin), [3] word of the Lord came to the priest Ezekiel son of Buzi, in the land of the Chaldeans by the river Chebar; and the hand of the Lord was on him there.

[4]As I looked, a stormy wind came out of the north: a great cloud with brightness around it and fire flashing forth continually, and in the middle of the fire, something like gleaming amber. [5] In the middle of it was something like four living creatures. This was their appearance: they were of human form. [6] Each had four faces, and each of them had four wings. [7] Their legs were straight, and the soles of their feet were like the sole of a calf’s foot; and they sparkled like burnished bronze. [8] Under their wings on their four sides they had human hands. And the four had their faces and their wings thus: [9] their wings touched one another; each of them moved straight ahead, without turning as they moved. [10] As for the appearance of their faces: the four had the face of a human being, the face of a lion on the right side, the face of an ox on the left side, and the face of an eagle; [11] such were their faces. Their wings were spread out above; each creature had two wings, each of which touched the wing of another, while two covered their bodies. [12] Each moved straight ahead; wherever the spirit would go, they went, without turning as they went. [13] In the middle of the living creatures there was something that looked like burning coals of fire, like torches moving to and fro among the living creatures; the fire was bright, and lightning issued from the fire. [14] The living creatures darted to and fro, like a flash of lightning.

[15] As I looked at the living creatures, I saw a wheel on the earth beside the living creatures, one for each of the four of them. [16] As for the appearance of the wheels and their construction: their appearance was like the gleaming of beryl; and the four had the same form, their construction being something like a wheel within a wheel. [17] When they moved, they moved in any of the four directions without veering as they moved. [18] Their rims were tall and awesome, for the rims of all four were full of eyes all around. [19] When the living creatures moved, the wheels moved beside them; and when the living creatures rose from the earth, the wheels rose. [20] Wherever the spirit would go, they went, and the wheels rose along with them; for the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels. [21] When they moved, the others moved; when they stopped, the others stopped; and when they rose from the earth, the wheels rose along with them; for the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels.

[22] Over the heads of the living creatures there was something like a dome, shining like crystal, spread out above their heads. [23] Under the dome their wings were stretched out straight, one toward another; and each of the creatures had two wings covering its body. [24] When they moved, I heard the sound of their wings like the sound of mighty waters, like the thunder of the Almighty, a sound of tumult like the sound of an army; when they stopped, they let down their wings. [25] And there came a voice from above the dome over their heads; when they stopped, they let down their wings.

[26] And above the dome over their heads there was something like a throne, in appearance like sapphire; and seated above the likeness of a throne was something that seemed like a human form. [27] Upward from what appeared like the loins I saw something like gleaming amber, something that looked like fire enclosed all around; and downward from what looked like the loins I saw something that looked like fire, and there was a splendor all around. [28] Like the bow in a cloud on a rainy day, such was the appearance of the splendor all around. This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord.

New Oxford, 1st ed.: 1:1-3:27: The call of Ezekiel. 1:1-3: Superscription. The thirtieth year, perhaps the thirtieth year after Ezekiel’s call, and if so, the date of the initial composition of the book, 563 B.C. (compare Jer. 36:1-2). Fifth day of the fourth month . . . , fifth year of the exile would be July 31, 593 B.C. This is reckoned from a lunar calendar, with the year beginning in the spring. The name Ezekiel means “God strengthens.” Chebar, a canal which is mentioned also in the Babylonian records, flowing southeast from its fork above Babylon, through Nippur, and rejoining the Euphrates near Erech. Hand of the Lord expresses Ezekiel’s sense of divine compulsion (3:14,22; 8:1; 33:22; 37:1; 40.1). 1:4-28a The throne chariot vision. Compare the imagery in 1 Kg. 22:19-22; Is. 6:1-9. 4: Out of the north, a literary figure drawn from Canaanite mythology, according to which the gods lived in the north. Stormy wind (1 Kg. 19:11), cloud (Ex. 19:16), and fire (1 Kg. 19:11-12) are all elements in the theophany (manifestation) of God. 5: The living creatures (Rev. 4:7) are cherubim, guardians of God’s throne (see Ex. 25:10-22; 1 Kg. 6:23-28), namely winged human-headed lions or oxen, symbolizing mobility, intelligence, and strength. 15-21: The four wheels (compare the four faces of the creatures) symbolize omni-direction mobility. 22: In ancient cosmology, the firmament separated the waters above the earth from the earth (Gen. 1:6-8). 26-28: Thus the Lord was enthroned above his creatures; compare the Lord enthroned above the cherubim in Ex. 37:9 (on the ark); 1 Sam. 4:4.

NOAB: 1:1-3:27: Part 1: The call of Ezekiel. 1:1-3: Superscription. Ezekiel was a Zadokite priest (v. 3, 44:15-31n.), steeped in the traditions of Jerusalemite royal theology (Zion theology; see Introduction). Despite his exile, he never loses his priestly role (cf. 43:12n.). The thirtieth year, probably Ezekiel’s own age. At the age for assuming his duties at the Jerusalem Temple (Num. 4:3), Ezekiel sought solitude outside his settlement (see 3:14-15) to reflect on what course his life might instead take in exile. Fifth day of the fourth month . . . fifth year of the exile would be July 31, 593 BCE. Chebar, a canal, flowing near Nippur, which is mentioned also in Babylonian documents. 3: The name Ezekiel means “God strengthens.” Hand of the LORD (3:14,22; 8:1; 33:22; 37:1; 40:1), Ezekiel undergoes the same sort of divine compulsions and ecstatic trances experienced by Israel’s early prophets, such as Elijah and Elisha (1 Kings 18:46; 2 Kings 3:15). Chaldeans, Babylonians. 1:4-28a: The throne-chariot vision. Cf. the imagery in 1 Kings 22:19-22; Isa 6:1-9. The first two-thirds of Ezekiel’s vision of God merely describes the creatures and wheels below the platform supporting God’s throne. In Ezekiel’s theology of God’s transcendence, God is clearly far removed from earthly perception. 4: Stormy wind . . . cloud . . . and fire are phenomena often associated with appearance of God in the Hebrew Bible (see Ps 18:8-12). Out of the north, because the shape of the Fertile Crescent meant that anything coming from Jerusalem arrived in Babylonia from the north. Something like, Ezekiel uses the word like to suggest the difference between his description and the transcendent reality itself. 5-14: The living creatures are identified as cherubim in a later vision (10:15,20), guardians of God’s throne (see Ex 25:18-22; 1 Kings 6:23-28), namely winged, human-headed lions or bulls. Uncharacteristically, the creatures Ezekiel sees have four faces (v. 10; cf. Rev 4:7). 13: Torches, cf. Gen 15:17. 15-21: The four . . . wheels (compare the four faces of the creatures) to God’s throne are a crucial element in Ezekiel’s reckoning of his central priestly belief that God had elected and now dwelled in Zion with the early Zion’s coming destruction by the Babylonians (see Introduction). Its wheels mean that the real, cosmic Zion-throne has omnidirectional mobility and is not tied down to earthly Jerusalem. See further 1:26-28n. 18: Full of eyes, symbolic of omniscience (10:12, Zech 4:10; cf. Rev 4:6,8) 22-25: A dome, referring to the cosmic firmament of Gen. 1:6-8, which separates earth and heaven. Jerusalem and its Temple mount symbolize the cosmic mountain where heaven and earth intersect at the dome. 26-28: Thus the Lord was still really enthroned atop the cosmos, even though Jerusalem, the symbol of God’s cosmic dwelling (Ps 26:8, 63:2, 102:16), was to be destroyed by the Babylonians. On the glory of the Lord, see 10:1-22n. Appearance of the likeness, the qualified language again emphasizes God’s transcendence and cosmic power (see 1:4n.). God’s self is three levels removed from Ezekiel’s description of God.

As we compare these two versions, we note several things. The later edition contains all the information in the former, but often explained somewhat more leisurely and simply. A few strange notes have been cleaned up (look at the notes to verse 4 – the “from the North” refers to Jerusalem, not to some Canaanite belief – the more recent version is actually the more respectful to the text. And words unlikely to be known by the average undergraduate, such as “theophany” are omitted (on the other hand, were the undergraduate using the earlier edition, she’d learn a new word.) The NOAB is much more effective at verses 26-28 at explaining some of the reasoning behind the vision of the chariot – the idea of a heavenly temple and heavenly Jerusalem. Thus rather than the earlier edition’s brief: “Thus the Lord was enthroned above his creatures,” the NOAB has a more meaningful discussion: “Thus the Lord was still really enthroned atop the cosmos, even though Jerusalem, the symbol of God’s cosmic dwelling was to be destroyed by the Babylonians.”

Recall my three evaluation criteria for academic study Bibles – as a classroom text, as a self-study guide, and as a reference. Here, I would argue that the newer edition, with its clearer explanations, was superior to the older editions as a classroom text and for self-study. But as a reference, perhaps it is a tie – the newer edition contains more material and is easier to understand, but the earlier edition included terse notes especially appropriate for someone who needs to extract information quickly and non-systematically.

Classroom value is further enhanced by the essays were written by the editors (those items in italics were section introductions)

- Brettler: Pentateuch, Historical Books, Poetical & Wisdom Books, Canons of the Bible (w/Perkins), Hebrew Bible’s Interpretation of Itself, Jewish Interpretation in the Premodern Era

- Coogan: Textual Criticism (w/Perkins), Interpretation of the Bible: From the Nineteenth to the Mid-twentieth Centuries, Geography of the Bible, Ancient Near East

- Newsom: Prophetic Books, Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, Christian Interpretation in the Premodern Era, Contemporary Methods in Biblical Study, Persian & Hellenistic Periods

- Perkins: Gospels, Letters/Epistles, Translation of the Bible into English, New Testament Interprets the Jewish Scriptures, Roman Period

An instructor can simply assign these essays, as well as the introductions to individual books, to a class – while I am not certain they would be sufficient reading for a challenging class, they certainly form a starting point. The essays are clear enough, albeit not particularly inspired.

Now, for the sake of discussion, let’s compare the NOAB’s annotations with those of the leading competitors, starting with HarperCollins Study Bible (HSB):

HSB: 1:1-3:15 Ezekiel’s inaugural vision, which may be compared with shorter, though similar, accounts in Isa 6; Jer 1. God calls Ezekiel to act as a prophet and provides him with instructions about fulfilling this task. Other vision reports are in 8:1-11:25; 37:1-14; 40:1-48:35. 1:1-3 The book’s introduction places the prophet in Babylonia and dates his activity by reference to a Judahite king, Jehoiachin, now in exile. 1:1 Thirtieth year, probably Ezekiel’s age when he experienced this vision. The river Chebar, a canal, not a natural river, near Nippur. 1:2 Jehoiachin, Ezekiel, and others were exiled to Babylon in 597 BCE. The fifth year of the exile would have been 593. This is the first of thirteen such chronological notices (1:2; 8:1; 20:1; 24:1; 26:1; 29:1; 29:17; 30:20; 31:1; 32:1; 32:17; 33:21; 40:1). 1:3 The priest, either Ezekiel or Buzi, though most probably Ezekiel. Ezekiel is defined as a priest because of his lineage, whereas he becomes a prophet because of this visionary experience. The land of the Chaldeans, the plains of southern Mesopotamia, associated with an Aramean-speaking people who had entered this area earlier in the first millennium BCE. The hand of the Lord, a phrase indicative of a spirit possession; cf. 3:14-21; 8:1; 3:22; 37:1; 40:1. This phrase is present at the beginning of each of Ezekiel’s four vision reports. 1:4-28 Ezekiel encounters God. The combination of cloud, fire, creatures, the spirit, and wheels makes it impossible to reduce this vision to some readily understandable phenomenon. 1:4-14 Ezekiel perceives strange creatures. 1:4 Fire and cloud are often associated with the appearance of the deity (e.g., Ps 18). Something like gleaming amber, also in 8:2. 1:5 The author uses like (see also vv. 22, 26, 27) to emphasize the vision is proximate. The prophet does not actually see the deity and his accoutrements. The living creatures are part animal, part human, with the latter dominant, i.e., they have two legs and stand upright. Such winged creatures with animal features are related to the seraphim in Isa 6, another “prophetic call” narrative. Ancient Near Eastern mythology knows such creatures, often minor deities, some of which support the divine or royal throne. Cf. 10:15, 20, where similar creatures are labeled cherubim. 1:7 Bronze, also in the description of a man in 40:3. 1:10 Four faces (human, lion, ox, eagle) on one head is otherwise unattested. The imagery may emphasize alertness: as the wheels turn, the creature will be able to look in any direction. 1:12 The spirit, not the deity, but the spirit of the living creatures in v. 21 (see also v. 20; 3:12.) 1:13-14 The creatures are associated fire or lightning; cf. Gen 3:24 for an analogous creature who brandishes a flaming sword; Gen 15:17, where torches symbolize the presence of the deity. 1:15-21 Crystalline wheels associated with the creatures. Although the writer mentions a wheel (v.15), there are apparently four wheels, one for each creature. Either a chariot with four wheels on one axle (two wheels on each side of the carriage) or a ceremonial cart with two axles (and two wheels per axle) may be presumed in this description. The imagery of wheels emphasizes that the glory of the Lord (v. 28) was capable of movement. The motif of wheels symbolizes the mobility of the deity who will later leave the temple (10:18-19). 1:18 Full of eyes implies the ability see everything (cf. 10:12; Zech 4:10). 1:22-25 Below the dome. 1:22 Dome, the heavenly vault (see Gen 1:7-8). 1:24 Auditory imagery (e.g., like the thunder) rather than visual imagery, fire and light, prevails. Both sound and visual imagery attend the appearance of the deity (e.g. Ex 19:16-19). The sound of mighty waters. Cf. 43:2. In Rev 14:2, the sound is further defined in association with thunder. 1:25 A voice, or “a sound,” from above the dome indicates that even the deafening roar created by the creatures’ wings under the dome is not the ultimate sound. 1:26-28 Above the dome. The throne above the heavenly vault signifies the throne or council room of the deity. The deity enthroned in the heavens truly transcends the temple. Like, used ten times in three verses to emphasize that Ezekiel does not actually see the deity. Sapphire. Cf. Ex 24:10. Like a human form begins the description of the deity above the loins (waist) like amber, below the loins like fire. 1:28 Rather than proceed with a more detailed and hence dangerous description, the author moves to an analogy, the splendor of a rainbow, and the summation This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord, which again emphasizes that the prophet did not see God directly (see note on 1:5).

This excerpt makes clear why the HSB was such a threat to the dominance of the NOAB – it contains substantially more detail and explanation. Still, the explanation is better at the verse level than at the passage level: it is highly repetitive (the annotator mentions repeatedly that Ezekiel did not actually see God) and still misses the main point of the vision (as explained in the NOAB) – namely the enthronement of God above the dome while Jerusalem falls. For these and other reasons which I will detail in my next installment, this study Bible is perhaps not quite as well suited for classroom use; although it is certainly a highly useful reference. (I should also mention that there were two typographical errors in the HSB annotations that I corrected in my extended quotation above – it is not a particularly carefully proofread edition.)

Next, I turn to the version in yet another competitor to the NOAB, the New Interpreter’s Study Bible (NISB), not to be confused with the well-known multi-volume set. Let’s see how it handles this passage. However, because of the great length of the NISB, I only quote here from the sections dealing up to verse 3:

NISB: 1:1-3:27 Ezekiel’s prophetic call stands boldly at the beginning of the book, declaring the Lord as the agent of history and Ezekiel as the responsive steward of the divine word. After a short introduction that sets Ezekiel firmly in time and space (1:1-3), the first chapter offers glimpses of Ezekiel’s enigmatic vision (1:4-28a). Ezekiel’s response (1:28b) leads to his commissioning, which unfolds in several divinely scripted scenes: commissioning (1:28b-3:11), preparation (3:12-15), instructions (3:16-21), and inauguration (3:22-27). 1:1-3 The double introduction (vv. 1, 2-3) answers several implied questions: Where are we? What is wrong? What is the remedy? The Lord provides a vision and speaks a word to a refugee community in the enemy’s land that challenges their cherished theological assumptions and empowers them to re-imagine their identity and mission. In the NT, 1 Pet 1:1, 2:11 reinterprets exile as a disengagement from dominant culture. 1:1 This autobiographical narrative reports on visions of God (only in Ezekiel; see also 8:3; 40:2). The divine perspective is opened as Ezekiel sees behind the scenes to glimpse the mystery of divine presence and absence. The thirtieth year refers either to Ezekiel’s birth (see also the induction of priests in their thirtieth year, Num 4:30) or to Josiah’s discovery of the scroll in the temple (2 Kgs 22). 1:2-3 A third-person narrator now identifies Ezekiel as a priest controlled by God’s hand. In 593 BCE, Ezekiel is commissioned to mediate the divine word that comes to him in a land considered unclean and, through him, to those who have lost everything.

This passage illustrates well the strengths and weaknesses of the NISB. On the one hand, the annotations are written in a much more conversational style than those of the NOAB or the HSB. On the positive side, one can simply read this study Bible as if it were the transcript of a lecture of a friendly instructor. But on the other hand, it speaks throughout (especially in this passage) in the language of social justice, which may be somewhat disconcerting to many readers; and it sounds more than a little like an excerpt from a sermon (e.g., the gratuitous reference to 1 Peter.) In fact, this particular passage is not representative of the annotations of the NISB – the politics are somewhat more dilute in the full text, although they are there. But the overall effect is somewhat anachronistic – and surprisingly applied – this is clearly a Christian reading of the Bible – seeking to answer the question “what is the relevance of this passage to us today?” If one is comfortable with the framework in which these annotations teach, then this is an ideal study Bible for self-study, since it considers simultaneously thematic issues as well as issues at the verse level.

One thing which surprises me about all of the above study Bibles is that they interpret this highly mystical of passages in terms of allegory – or, in the case of the NISB, in terms of societal needs. This surprises me, since a mystical experience is by definition that of an individual – here, as much as any place in the Bible, we have the experience of mysticism from the viewpoint of a prophet himself. The NISB’s reading here is most dissonant with this mystical aspect – it reads what is ultimately an individual (psychological) experience in sociological terms. However, the NISB also reflects the better angels of the Christian tradition, in refusing to miss a chance to learn a moral lesson from a Biblical verse, and ultimately showing the selflessness of the pure Christian worldview.

I will mention here briefly one additional study Bible: Oxford’s Jewish Study Bible (JSB) – see my previous review. This version has such extensive annotations that the annotations for this passage exceed in length the annotations for the NOAB, HSB, and NISB combined, so I will not quote from it here. Instead, I will simply mention that it discusses, alone among these study Bibles, the mystical aspects of Ezekiel’s vision, and also relates it to non-canonical works such as 3 Enoch, as well as covering both the connections with Ancient Near Eastern traditions as well as its allegorical meaning.

Layout and physical design: Oxford University Press produces excellent Bibles – perhaps among major publishers only Cambridge University Press produces nicer Bibles. One of my old editions in this series stayed with me for years, suffering daily abuse, and it stood up surprisingly well to such regular use. The newer NOAB is larger, and has a glossy hardcover (it is also available in bonded leather edition) but the binding is excellent. The typography and print has never been clearer than it is in the third edition – the print is relatively large – larger than any of its NRSV competitors and the spacing in the notes is wide enough to make them easily readable. The paper is slightly translucent, but bleed through is limited and does not cause a problem (unlike the HSB).

A Leftward Turn?

There is something about Bibles that causes a certain sort of person to mutter about heresy. The NOAB has been criticized for being different than the Second Edition, and these charges rose to such a degree that Oxford University Press was forced to make a response :

What criticism in particular has been made against the NOAB? Well, a summary of the criticism can be found an article published by a conservative group. While the tone of the article speaks for itself, we can examine the claims it puts forwards:“This third edition of the classic New Oxford Annotated Bible represents not only a revision of a classic textbook and biblical reference work for the general reader, but nearly an entirely new book. . . . More Catholic scholars, a new group of Jewish scholars, more women, and scholars from a wider diversity of backgrounds (African-American, Latino, and Asian-American), joined the distinguished roster of contributors. The variety of interpretations, liberal and conservative, was increased. . . .

“There has been a focus in certain circles of Christian comment on these changes from traditional understanding. It is important to recognize that Oxford University Press is not aiming at influencing any current social or political trends, whether within secular society or within any church or denomination. The annotators and authors of the essays were given general instructions to guide them in writing their study materials, but except for specific indications of the length of their submissions, and the format in which they were to be submitted, they were left free to determine what they would comment on and how those comments would be shaped. The editorial board and Oxford staff reviewed every submission, and suggested numerous changes, but every revised version went back to the original author for acceptance or adjustment of the changes. No contributor was made to say anything with which he or she disagreed. It would have been impossible for one editor to impose a personal view or agenda on this process, and no editor attempted to do so. The views expressed in any of the annotations are the scholar's own, as that scholar understands the research of colleagues on the particular book of the Bible being commented on.”

- Claim: The NOAB is soft on homosexuality. I have found no passage in the notes that suggests that Bible permits homosexuality; indeed, the cited annotations make clear that homosexual behavior is unacceptable [Genesis 19:5 “disapproval of male homosexual rape is assumed here”; Romans 1:26-27 “Torah forbids a male ‘lying with a male as with a woman'"]. The comment on 1 Corinthians 6:9-11 appears to be making the same point (in a fashion appropriate for a textbook) that Rick made in this post.

- Claim: The NOAB denies Christ’s divinity. Given that belief in the divinity of Jesus is a central belief of Christianity, it would be quite surprising if this claim found support. Here, a single annotation in the book of John is quoted out of context, ignoring many other annotations which indicate that Jesus is divine in the book of John (e.g., the Introduction “It demonstrates that faith in Jesus is equivalent to faith in God . . . .”; 14:20 “their relationship with the risen Jesus will reflect the union of the Son with the Father.”

- Claim: The NOAB is soft on abortion. The claim is made that Psalms 139:13 is a prooftext for anti-abortion – I am frankly unconvinced of this reading; in any case, Jeremiah 1:5 is a much stronger notion (that God knew and selected the prophet before he was formed in the womb) and the annotation here is quite strong: “Knew, connotes a profound and intimate knowledge.”

- Claim: One NOAB editor has previously worked with member of a Christian outreach group to homosexuals. A claim is made that one of the editors worked on a project with a leader of a ministry group that reaches out to homosexuals. In an academic setting, I don’t feel it is appropriate to engage in such ad hominem attacks.

- Claim: The NOAB is infecting the Christian Mainstream. The claim is made that since the NOAB is the official text of the United Methodist Church’s Disciple Bible Study program. Of course, since this essay was published, the UMC’s publishing house, Abingdon, has produced its own study Bible, the NISB. As my quotation above showed, the NISB sometimes rather explicitly reflects a political agenda. In contrast, the NOAB is a much more neutral annotated text.

A claim is also made in the article that Bruce Metzger wrote “I have read your perceptive comments about the two editions of the Oxford Annotated Bible and am in full agreement with your evaluations.” Unfortunately, we don’t know exactly what evaluations Metzger is in agreement with; this comment appears to me to be taken out of context.

The disconcerting aspect for me is that in some ways the NOAB is a more traditional understanding of the Bible than earlier editions. The passage I analyzed above has in an early edition a reduction of Ezekiel’s experience of a wind from the North to Canaanite myth; in the current edition this is clearly explained as being from Jerusalem. While earlier editions a certain detached skepticism in earlier editions, the newer edition treats the philosophy of biblical inerrancy with much greater respect.

Nonetheless, the approach of this study Bible is historical-critical and it is not designed for devotional purposes. The NOAB’s contributors do reflect a diversity of views, including traditional views. Since the NOAB no longer has a “lock” on the study Bible market, if readers feel that it offends they have many other places to go. But to return to the question I started with, I know of no other study Bible as appropriate for a (secular) college classroom.

Final thoughts

The NOAB no longer looks as special as it once did: the contributors are in some cases less distinguished than their predecessors; and there is a wealth of different study Bibles to choose among. Still, the NOAB remains the most widely used study Bible in college classrooms and with good reason: the annotations are brief and insightful. One way in which it can be measured is that it serves as a benchmark: in marketing literature, publishers measure other academic study Bibles against the NOAB. While for many readers there might be a better alternative, one can certainly do worse than the NOAB. A person who reads it will have an excellent foundation in Biblical studies.

Coming up next: “The contender” – the HarperCollins Study Bible, 2nd edition.

TNIV Truth: 1 Peter 4:12

The Great Apple Blunder of 2007

Today, while I'm sure that there are a few exceptions here and there, I would guess that most folks like me who use a Mac do so by choice. That's true for a lot of Windows users, too, but for many it's not true. I would guess that for many Windows users, if given good compelling reasons to switch, and given the ability and opportunity to do so, they might just make the move.

That brings us to the current situation here in 2007. This year saw the release of a new Windows OS, Vista, and the promise of a new Mac OS, Leopard (OS X 10.5). Originally, Steve Jobs promised that Leopard would ship pretty much at the same time as Vista. That didn't happen, but we were told that Leopard would ship before the end of the Spring (which if held true would have probably been pretty close to the beginning of summer).

Then on April 12, Apple made a surprise announcement: Leopard will be delayed until October so that Apple's engineers can concentrate on bringing the iPhone to market. I'd simply link to the announcement, but there's no separate page for it. It's in the list on Apple's "Hot News" page and presumably will eventually scroll off once other news items are added. But here it is in its entirety. If you've already read it, simply move on to the next paragraph.

iPhone has already passed several of its required certification tests and is on schedule to ship in late June as planned. We can’t wait until customers get their hands (and fingers) on it and experience what a revolutionary and magical product it is. However, iPhone contains the most sophisticated software ever shipped on a mobile device, and finishing it on time has not come without a price — we had to borrow some key software engineering and QA resources from our Mac OS X team, and as a result we will not be able to release Leopard at our Worldwide Developers Conference in early June as planned. While Leopard's features will be complete by then, we cannot deliver the quality release that we and our customers expect from us. We now plan to show our developers a near final version of Leopard at the conference, give them a beta copy to take home so they can do their final testing, and ship Leopard in October. We think it will be well worth the wait. Life often presents tradeoffs, and in this case we're sure we've made the right ones.

Apple has been making computers for 31 years, this month. But due to the success of the iPod, iTunes, and the release of AppleTV and the upcoming iPhone, Apple Computer made the decision earlier this year to change its name to Apple, Inc. to reflect its diversity of product offering. In my opinion, the above announcement regarding the delay of Leopard says clearly that this is a company stretched way too thin. Computers are what made the company. No Mac user such as myself should begrudge these other products because in many respects, they've added to Apple's bottom line and in that regard have supported the ongoing development of Mac hardware and software. Yet, going all the way back to the mid-eighties and the context of that infamous Gates' memo, the Mac OS has been the underdog--the underdog that could've been the top dog.

Two days ago I had lunch with the owner of a computer/network consulting company for which I used to work a few years back. 99.99% of his company's work relates to Windows networks and workstations. Occasionally if he has a Mac issue, he sometimes will still call me, but that hasn't happened in a while. In the midst of our conversation, he made the statement, "By the way, I hate Vista." I was really taken aback by this. I've got a copy of Vista installed on my MacBook in Parallels. To be honest, I kinda like Vista, perhaps if nothing else because the interface somehow feels more Mac-like to me than previous versions of Windows. But then again, I only have a couple of Windows programs that I occasionally run, and I don't run these everyday. Vista is not mission critical for my work. I don't use Vista all day long. But he went on to describe clients of his who've had nothing but trouble with Vista.

And he's not alone. Certain federal agencies have placed a ban on upgrading computers to Vista. Earlier this week, a northwest CIO made headlines because he is contemplating moving his organization from Windows to Macs. Yesterday, I read that Dell Computers "will restore the option to use Windows XP on some of its home systems, marking a potentially damaging blow to Microsoft's hopes for the newer Windows Vista." Many of the individual complaints I've heard about Vista have to do with this or that scanner or assorted peripheral not working with Vista due to lack of drivers. People have short memories because I remember hearing similar complaints about Windows XP in 2001, but eventually solutions were found for most problems. Nevertheless, while people have always complained about Windows in one form or another, I don't remember ever seeing this much discontent and this much balking to the idea of upgrading to a new Windows OS.

And that brings me back to the old "strike while the iron is hot" idea. It's already too late to take advantage of it, but Apple was handed a prime opportunity to take advantage of Vista's shaky reception by pushing the Mac as a more suitable upgrade. Granted, the current Mac OS (Tiger) is extremely stable and can hold its own against Windows, but what a missed opportunity on Apple's part not to offer their new OS, Leopard, at the same time as Vista!

But this is the new Apple, Inc., not Apple Computer. And I believe that what a lot of Mac users feared when the name change was announced is coming true--the computer division of Apple is taking a back seat to its other product offerings. In spite of their growth, Apple's announcement to delay Leopard not only proves that they don't have the resources to steer two new technologies simultaneously, but also that the older product takes a backseat to the newer.

Of course, Apple is betting on the iPhone becoming a huge success. And maybe it will. But who knows? And I'm sure there's a rush to get the iPhone to the market before the copycats bring forth their phones. Personally, I'd love to have one, but not at that price tag. Plus, we all know that the first generation iPhone will not be the one to get. Let the early adopters suffer through the first incarnation and then the rest of us who want to can get one when the second or third generation is released (in the meantime, I haven't renewed my Sprint contract).

Nevertheless, Apple missed a great opportunity by delaying Leopard and putting all of it's resources on a market it has no history in. And they did it on the risk of an unproven product. Hopefully it will work out for the best, but by the time Leopard is finally released, Vista's kinks may well be worked out, and the iron will no longer be hot.

Where Did I Hear This Joke?

Bible Version Cage Match Round 3 Posted at Lingamish

If you are just now tuning into the series, be sure to read Round 1 (also written by David) and Round 2 (written by yours truly).

READ THIS NEXT SENTENCE VERY FAST TO GET THE SENSE OF HOW I INTEND IT TO BE HEARD: And of course, there's still the post out there that was almost Round 3, in which David called his method and motives a scam, but I thought he was referring to the whole series as a scam, and I took great offense because the work on my part was certainly 100% scam-free, but David

Stay tuned because at some point in the near future, Round 4 will be posted here. I haven't selected a passage yet, but if you have suggestions, feel free to post them as long as your motives aren't "scam-motivated."

Quest Bible Study Class Gets Mention from KBC

See "Sunday School New Birth Stories, part 3."

And if you're not in the class already, but if you're ever in the area, come join us at 10:30 a.m. on Sunday mornings.

TNIV Truth: Hebrews 11:11

In my newest entry, on TNIV Truth, I examine the differences between the NIV and TNIV in Hebrews 11:11. See my post, "NIV vs. TNIV: Hebrews 11:11."

Bible Translation Awareness (or lack thereof)

I'm not overly concerned with which particular translation a person uses as long as the interaction between the person and the version is meaningful. When occasionally asked what translation I recommend, my overarching recommendation is that a person reads a modern translation for a primary Bible. I never recommend the King James Version because in my two decades of teaching experience, the language and vocabulary--as beautiful as they are--is mostly not understandable by the person reading this Bible. I'm not opposed to the KJV, per se, and suggest it is fine to be read in parallel with a modern translation, but I believe it is past its use for the large majority of people in today's culture. Nevertheless, according to the April CBA bestsellers list, the KJV is ranked at #2 (under the NKJV), so a lot of folks are still buying it. Obviously, they haven't asked my opinion!

When I say a modern translation, I'm not trying to proclaim bias against the very beautiful and useful translations of the past. But the reality is that our language is changing, perhaps moreso right now than in the last hundred or more years. Further, and more importantly, I believe that modern translations have the benefit of textual criticism and ongoing linguistic research to create translations in English that more accurately reflect the message and intentions of the original biblical writers. I'm especially interested in how well 21st century versions (ESV [2001], The Message [2002], HCSB [2004], NLTse [2004], NET Bible [2005], and TNIV [2005]) render the biblical texts. Future posts will focus on these translations, and I'll probably include a couple of late 20th century versions which I believe still hold significant voices in the discussion, namely NRSV (1989) and the NASB update (1995).

Of course, while my main recommendation is for a modern translation, it's no secret to any reader of this blog that I have certain translations I favor. And when asked for particular recommendations in the last year or so, I've primarily recommended the NLT, TNIV, and HCSB. After elaborating on the differences between them, I've suggested that a person go to a local bookstore and read passages in all three. Of course, such a suggestion always opens the door to a sales clerk intruding into the process to push a favorite translation and dissuade the purchase of one that I may have recommended. If you don't believe this happens, go to a Christian bookstore and hang out in the Bible section for awhile. Play dumb about translations when the sales clerk comes over, and you'll often see an agenda in place for pushing a particular version.

All this leads me to bring up an article I received this morning in a Google News Alert of which I have a number of subscriptions pertaining to various Bible translations. This is yet another article in which the writer seems to be surprised that the Bible is still such a bestseller, outselling even Harry Potter (who would've thought it?!). But the context of this particular article is different because it relates to a vote that the Muscogee County (Georgia) Schoolboard will make on April 23 as to which translation of the Bible will be used in their new Bible-as-literature elective. Care to guess which translation the superintendent is recommending? The New KIng James Version (which happens to be #1 on the April CBA list). I've wondered over and over who is buying the New King James, a translation in general that I would only recommend to a diehard KJV-only adherent as a compromising alternative. Such a suggestion by the superintendent and much of the other information in the article itself suggest to me that I'm very much correct about the state of unawareness when it comes to Bible translations. Consider the following:

- In attempt to update the reader on other translations besides the KJV, the writer Allison Kennedy offers brief publication background on three "newer" translations: the NIV, NASB, and NKJV. Such a list would have been understandable if this article had been written in say, 1985, but there has been much significant progress made since these three translations. Of note, Kennedy doesn't even mention the 1995 update to the NASB which makes me wonder if she was using an older source for her information.

- From the article: "Joy Ahlman is a student of the Bible who takes her translations seriously. For years, the Christ Community Church member used the New International Version and the New Living Translation because both have clear language, but now she's recently switched to the New American Standard. 'I prefer to take time to study and it has cross-references and translations of different words at the bottom.'" Well, it will certainly take Joy more time to plow through the NASB than the NIV and NLT, but I'm more stunned at her reason for switching regarding "cross-references and translations of different words at the bottom." Such features are readily available in editions of the NIV and NLT, too. But such a statement demonstrates a common confusion between text and features in the minds of many Bible readers. Many times I've had to explain the difference to a church member between the text itself as the actual scripture as opposed to study notes and other features. And I've also had to explain that two editions of Bibles don't mean two different translations.

- And of course, KJV-only adherents weigh in for Kennedy's article: "'I teach and preach from the King James,' said Vann, pastor of The Rock Baptist Church in Cataula, Ga. 'The reason I do that is because newer translations leave out certain words or phrases. It's not that I'm a King-James-only guy, but it makes the people dive in deeper.' Last year, Vann led the church through a study comparing some of the translations. 'It blew their socks off,' he said of his members, many of whom weren't aware of the differences." Yeah, I bet. They're so concerned about things being taken out of their Bible, they don't realize they're buying into a textual tradition in which things have been added that the biblical writers never wrote. You'd think that there would be concern that goes both ways. A little bit of text critical knowledge would go a long way in such situations.

- Granted, this is a nitpick, but at one point Kennedy calls the New Living Translation the "New Living Bible" and says that it comes in many versions, although what she means is that it comes in many editions.

- Interestingly, in the entire article, there was no mention of the ESV or TNIV, which may say more for the awareness of these particular translations than anything about the writer of the article.

When I taught Bible at a private Christian school for five years, I allowed students to use any translation they wanted with the exception of the King James Version. Although I've mainly used the TNIV over the past year while teaching, I haven't pushed it as a translation. In over twenty years of teaching the Bible in various venues, I've always encouraged a variety of translation use, and I've only said anything to something about their translation on a very small handful of occasions. I've made a point not to put down any particular translation. And any concern has usually been in regard to use of the KJV in which I felt they consistently misunderstood what what they were reading. Sometimes, I merely offer a Bible as a gift without making a big deal about their use of the KJV such as recently when I gave a copy of the NLT to a member of the class I teach on Sunday mornings. He now carries it every Sunday and has told me that he feels like he can understand the Bible for the first time in his life.

My overriding concern is that people have a life-changing experience with God's Word. I never want a particular translation to get in the way of that possibility. What's translation awareness like in your circles? Is it is a big deal? Should it be addressed occasionally or should it be ignored? Feel free to post your thoughts in the comments.

The Wycliffe New Testament [1388] (Top Ten Bible Versions #9)

And shepherds were in the same country, waking and keeping the watches of the night on their flock. And lo, the angel of the Lord stood beside them, and the clearness of God shined about them, and they dreaded with a great dread. And the angel said to them, Nil ye dread, for lo, I preach to you a great joy that shall be to all people. For a Saviour is born today to you that is Christ the Lord in the city of David. And this is a token to you, ye shall find a young child lapped in cloths and laid in a creche. And suddenly there was made with the angel a multitude of heavenly knighthood, herying God and saying, Glory be in the highest things to God, and in earth peace to men of good will.

From the Gospel of Luke, chapter II

I've said before that my "Top Ten" list of Bibles is somewhat categorical in nature. One of the categories that I wanted to see represented in this series when first thinking about it was translation of a historical nature, a non-contemporary translation. I could have easily and logically picked the KJV, but it is so familiar, I doubt I could have added anything to the conversation. I came close to selecting the Geneva Bible or William Tyndale's translation, but I remembered that the era surrounding John Wycliffe had always captured my imagination.

I first discovered John Wycliffe (1320-1384) and his Lollard followers in college when I took a class devoted to Chaucer's writings. I felt immediate theological attraction to this individual often called "the morning star of the Reformation" and his conviction that all believers have a copy of the scriptures in their own native language. Later in seminary, while taking a church history class, I focused my attention on Wycliffe again as the subject of my term paper for that semester.

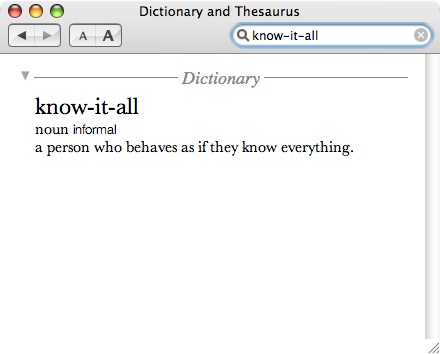

Then a couple of years ago, I was sitting in a seminar and I noticed one of the church history majors was reading from a very interesting Bible. Always interested in what version of the Scriptures people are reading, I looked closer to see The Wycliffe New Testament 1388 on the spine. Very much intrigued by this point, I asked him if I could look at it. He cautioned, "Yeah, but you should know that it's in Old English." Remembering my Chaucer class from years before, in which we were only allowed to read the texts in their original form in class (no modern translations or paraphrases allowed), I did my best not to sound too much like a know-it-all as I said, "Technically, that would be written in Middle-English." He looked at me with a blank stare and then said, "No, I think this is Old English." I saw him a few weeks later, and he said, "Hey, you were right--the Wycliffe Bible is written in Middle-English."

Thanks. It's probably a good thing that I didn't bring up the fact that it's very doubtful that Wycliffe had much direct influence on the translation that bears his name. Rather, most agree that the Wycliffe Bible (there were actually two different versions by that name) was produced by the Lollard community which was heavily influenced by John Wycliffe's teachings. The translation itself, while not the very first translation of the Scriptures into English, were the first product of Wycliffe's conviction that all believers, regardless of education or status had the right to access the Scriptures in their own language. The basis of the Wycliffe New Testament was the Latin Vulgate, which was ironically itself once a translation with the same goal but became a Bible for the privileged as fewer people spoke Latin.

Original copies of the Wycliffe NT were written and copied by hand. Since ownership of these texts was illegal, having a copy was a great risk. They were also very valuable, often with wheelbarrows of hay being traded for a few pages from the "pistle" of James or some other NT book. According to the introduction found in the printed copy I own, these handwritten pages of Scripture were highly treasured even long after the age of the printing press and the explosion of English translations in the sixteenth century. They only fell out of use after dramatic shifts in the English language.

The Wycliffe NT is somewhat unique because it contains the epistle to the Laodiceans, which is evidently in the Vulgate, but is no longer extant in the Greek. Although the Lollards recognized that the Catholic Church did not consider this book to be canon, they nevertheless did, assuming that it was the letter referred to in Col 4:16.

I picked up the same edition of the Wycliffe NT that the student mentioned above had. It's a very solid hand-sized hardback binding with a nice blue ribbon, published by the The British Library in association with the Tyndale Society. The pages are made from "normal" paper as opposed to Bible thin paper, and I would guess that they may be acid free. This New Testament uses a stitched binding so no doubt, it will hold together for quite a long time. If one might be prone to take notes, there are ample one inch margins interrupted only occasionally with a definition of an overly-archaic word in the text. Spelling has been modernized, and (unfortunately, in my opinion) so have many of the words. This is not really a difficult read--nothing like my Chaucer class--but it will slow down the average reader (which is often a good thing). Why some archaic words were updated and others were left alone, I have no idea. Like the original Wycliffe NT, this edition does not have verse divisions, but does contain chapter numbers.

The order of books is different from our Bibles with Acts (or "Deeds" in this version) coming after Paul's "pistles" which not only include the aforementioned letter to the Laodiceans, but also includes the letter to the Hebrews, assumed by most in the Middle Ages to have been written by Paul. For some odd reason, there's no table of contents which would have been very helpful because of the non-standard arrangement of books.

Some passages of interest:

And Jesus, seeing the people, went up into an high hill, and when He was sat, His disciples came to Him. And He opened His mouth and taught them, and said, Blessed are poor men in spirit, for the kingdom of heavens is theirs. Blessed are mild men, for they shall wield the earth. Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted. Blessed are they that hunger and thirst rightwiseness. for they shall be fulfilled. Blessed are merciful men, for they shall get mercy. Blessed are peaceable men, for they shall be called God's children. Blessed are they that suffer persecution for rightfulness, for the kingdom of heavens is theirs.

...