The New American Standard Bible (Top Ten Bible Versions #3)

The NASB has been my close companion for over two and a half decades. Perhaps we have spent so much time together, that like a spouse or a good friend, I have trouble seeing the flaws that other more objective individuals might see more clearly. This is my desert island Bible. This is the translation from which I have memorized Scripture, the first translation I read all the way through, the first translation I ever preached from, the translation I have most often used to check my own translation from the original languages. The NASB is the first Bible that really spoke to me--the first one in which I really began to hear God.

In spite of a longtime practice of comparing translations in my personal Bible study, appreciating other translations and reading through them, the S in NASB was just that--it set the STANDARD in my understanding of God's Word. This is why it was such a big deal for me to drop the NASB a few months back in favor of the HCSB and TNIV for public use. Rest assured, I did not make such a change for myself, I made it for those whom I teach.

Brief History of the NASB. Like the NIV, the New American Standard Bible came about as a reaction to perceived liberal bias in the Revised Standard Version of 1956. I won't go into those issues here, especially since many of them now seem much more trivial than they did a half-century ago. The RSV had been a revision of the 1901 American Standard Version, and since the copyright of the ASV had expired, the Lockman Foundation of La Habra, California began work on its own revision in 1959. The entire Bible was published in 1971, and the translation was updated again in 1995.

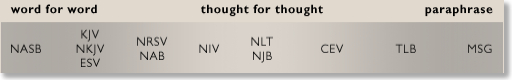

Almost every evaluation I've ever read of the NASB rates it as the most literal of the major modern translations, and from my experience I would certainly agree. Every chart comparing various translations puts the NASB at the extreme of the form-driven Bible versions. Below is an example from Tyndale House Publishers' website:

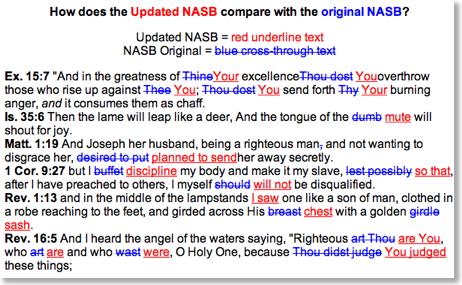

The Lockaman Foundation itself makes no bones about this standing. With the 1995 update came the slogan, "The Most Literal Translation is Now More Readable." Having used both the 1971 edition and the 1995 edition, I can vouch for this fact. The original NASB still retained archaic words such as "thee" and "thou" for any texts that addressed deity. The 1995 update removed these words and updated other language as well. An example from the Lockman website provides a good example of the kinds of changes that were made:

The 1995 update also brought in some minor updates regarding inclusive gender, but nothing as far-reaching as the NRSV, NLT, or TNIV. Ultimately, the NASB primarily uses masculine universals, including 3rd person masculine pronouns. However, one example of such a gender change in the NASB is demonstrated in Matthew 5:15--

| Matthew 5:15 | |

|---|---|

NASB 1971 |

NASB 1995 |

| Nor do men light a lamp, and put it under the peck-measure, but on the lampstand; and it gives light to all who are in the house. | nor does anyone light a lamp and put it under a basket, but on the lampstand, and it gives light to all who are in the house. |

In the example above, also notice the change from "peck-measure" (which I always thought was an odd translation) to simply "basket."

Personal History with the NASB. As I have stated elsewhere, I initially had access to three versions of the Bible in my childhood. I had a copy of the King James Version which was given to me in my third grade Sunday School class so that we could follow along with the pastor. We had multiple copies of the Good News for Modern Man (TEV) paperback New Testament. And my grandmother gave me a children's edition of the Living Bible. Even at a young age, I stressed about what Bible to take to church. Although I could understand the Living Bible and the TEV, I was embarrassed about the word "Children" in former, and the latter looked like a paperback novel. I don't know why I've always wanted a Bible that "looks like a Bible," but such an obsession evidently started quite young. The KJV certainly looked like a Bible, but the Elizabethan English that it contained never communicated to me as a child.

In 1980 when I was thirteen, a friend of mine showed me his Thomas Nelson Open Bible (handsize edition) in the NASB. I pored through his copy during an entire worship service. Not only did I like some of the reference features (the topical index in the front of most editions of the Open Bible is still one of the best I've ever seen included with a copy of Scripture), but more importantly, I could read the translation and it made sense to me. People criticize the NASB for being overly literal and wooden, but it's readability to me, a thirteen-year-old (and granted, I was a strong reader) was light years away from the old King James Version which often came across as unintelligible. Consider also, that this was before so many of the translations that we have now, some of which are specifically aimed toward young readers. For me, my friend's NASB spoke English I could comprehend. This was the Bible I had to have.

The next week, I got off the school bus downtown and made my way to our small little Christian book store. I held $10 in my pocket that I had received earlier as a gift. Once in the store, I walked right up to the counter and told the clerk that I wanted a copy of the Open Bible: New American Standard, in bonded leather. It was in stock AND they could put my name on the cover for free. Everything was set until I went to pay. It was $40, much more than what I expected. In fact, I had assumed that I'd have change left over after the transaction. Seeing my disappointment, he suggested that I put my $10 down and let them hold it as a layaway.

So, I put my Bible on layaway and went home. Later I recounted the story to my parents, and later in the week my father went to the store and paid the rest of the price. There were, after all, worse things that a thirteen-year-old could spend his money on.

For the next 25 or so years, the NASB was my primary translation of choice. I memorized it, studied it, preached and taught from it. I went through four different editions of it during that time, the latter two of which were the standard side-column reference editions. I came to the point around 1990 that I didn't want someone else's study notes in my Bible. I preferred to write my own notes in the margins after my own careful study. I did not initially switch from the older NASB when the update came out in 1995. All of my old notes were written in the Bible I had been using! However, I had begun at some point translating "thee," "thou" and "thy" to "you" and "your" on the fly as I read aloud from it. However, around 2001, I read a passage without making the change, and a ministerial friend kidded me about using such an "old" Bible. So in 2002, I switched to the updated NASB and began a tedious process of transferring my old notes. They still aren't all transferred, and frankly, I don't know if they ever will be.

Evaluation of the NASB. The Lockman Foundation, also the sponsors of the Amplified Bible and two translations in Spanish, promote a "Fourfold Aim" for all their publications:

1. These publications shall be true to the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

2. They shall be grammatically correct.

3. They shall be understandable.

4. They shall give the Lord Jesus Christ His proper place, the place which the Word gives Him; therefore, no work will ever be personalized.

These four aims are presented right at the beginning of the Foreword, found in all editions of the NASB. I would think that it's fair to judge the NASB on these criteria.

Starting with the fourth aim, although I've seen these statements countless times, I realized today that I have no real idea what's being communicated here, especially in the statement, "no work will ever be personalized." What do they mean by this? I could find no commentary on the Lockman website for these aims, but I sent them an email asking about it this morning. Perhaps someone reading this blog entry will have some insight. Usually statements like this are in reaction to something else. Was there a translation at some time that did not "give the Lord Jesus Christ His proper place"? Was there a translation that was "personalized"--whatever that means?

Points 2 and 3 can be taken together. In my opinion the NASB met these aims better in 1971 than perhaps it does today in light of the explosion of English translations that we've seen since that time. Compared with the King James Version, for me, the NASB certainly was understandable. And grammatically, it fared better then than now. The KJV doesn't use quotation marks for direct quotes, and the NASB did. However, the NASB as a product of its time does two things that can be particularly aggravating to me. I wish that when updating the translation in 1995, they had chosen to cease the outdated use of italics for words not found in the original languages, but added to give meaning in the English translation. As everyone knows, the problem with the use of italics is that in modern usage, it indicates emphasis. I've actually heard people reading from translations that still use italics for added words put stress on these words which usually makes for a nonsensical understanding of the passage. I understand the desire in a strict form-driven translation to make some kind of indication for added words, but perhaps the half-brackets used in the HCSB (which I find totally unnecessary in that translation) would be better suited in the NASB.

Secondly, I would personally prefer that a translation not capitalize pronouns referring to deity. Granted, most of the time, the context makes such a practice clear, but there are some places--especially in the Old Testament--where this would be open to interpretation. In the end, there's no real grammatical warrant for capitalizing such pronouns. Such practice, in my opinion, seems to be left over from the days of retaining "thee," "thou," and "thy" for deity (which also has no grammatical warrant).

There are other uses of language that could be pointed out. For instance, the NASB still regularly uses "shall" and "shall not" even though these words are becoming less used in contemporary English. One can occasionally find odd uses of words such as in Job 9:33, "There is no umpire between us, Who may lay his hand upon us both." Now granted, the word "umpire" is older than the game of baseball and has the meaning of one who is an arbiter, but this seems like such an unusual choice to use in an Old Testament text when the average reader is going to have a mental image of a sports official. Okay, I admit that I've used this verse in just such illustrations, but that's beside the point!

The strength of the NASB lies in the first goal of the Lockman Foundation, that it would be "true to the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek." For what it is, as a form-driven, literal translation in the Tyndale/KJV tradition, the NASB cannot be bettered. This is where its value lies. To get a close, but readable, English translation of what the original languages state, the NASB does the job. This is also why I personally favor the NASB over the ESV. I'm not going to use either for public reading, but for personal study, the NASB is simply more literal than "essentially literal."

However, having said that, the NASB's strength is also its weakness. It is so literal that most do not recommend it for public reading. I heard that accusation for a long time before I admitted to it, let alone stopped using the NASB in public. Again, I have used the NASB for so long and am so overly-familiar with it, that I tend (even now) not to notice its literary weaknesses.

And it's worth noting that while I used to be convinced that a form-driven translation is the most accurate kind of translation, I am no longer so easily convinced of that fact. That's been a philosophical change that's been slowly evolving in my thinking. This is evidenced by my use of the HCSB (which uses both form- and meaning-driven methods--what they call "optimal equivalency") at church and my increasing use of the TNIV elsewhere. Clearly, in some places, a form equivalent translation simply does not communicate an intended message. Look for instance at a passage like Genesis 4:6--

| Genesis 4:6 | ||

|---|---|---|

NASB |

TNIV |

NLT |

| Then the LORD said to Cain, “Why are you angry? And why has your countenance fallen? " | Then the LORD said to Cain, “Why are you angry? Why is your face downcast?" | "Why are you so angry?" the LORD asked Cain. "Why do you look so dejected?" |

The NASB accurately translates the literal sense of the text when God asks Cain why his "countenance has fallen." But there are a number of problems with this. First, will the average contemporary reader even know that the word "countenance" refers to one's facial expression? The TNIV is a slight improvement by using the word "face" instead. However, the verse speaks of a downcast face. Is this the way the average person speaks? Has anyone ever noticed you were in a bad mood and asked why your face was so downcast? Probably not. The New Living Translation, a fairly extreme meaning-driven translation, at the other end of the spectrum from the NASB, communicates the meaning of this phrase best by having God ask Cain, "Why do you look so dejected?"

To be fair, in many passages of the Bible, this kind of issue does not come into play. However, a form-driven translation like the NASB is weak when it comes to ancient idioms such as a "fallen countenance" that aren't in use in our culture today. Personally, I like knowing the original idiom, but I also know what a phrase like this means. Many readers may not. This kind of example is especially amplified in poetic sections of the Bible where metaphors and idioms abound. My opinion is that there's room for both form- and meaning-driven translations. And often ones that are somewhere in between, using the best of both translation philosophies, are best suited when reading in public.

I always considered the NASB to be an extremely accurate translation (as far as form-driven translation goes), but I noticed as I began pulling the HCSB into my Bible study alongside the Greek text and the NASB, that often the HCSB seems to be more accurate. I've written about this briefly before, and may have to say more at a later time.

If nothing else, the NASB, which was a great alternative for me to the KJV 25 years ago, seems to suffering from being a representative of a previous translation generation with its uses of things like italics and capitalized pronouns, while at the same time vying for a place with a whole new generation of versions such as the NLT, ESV, HCSB, and TNIV. For what it's worth, the NASB still outsells both the ESV and the TNIV, but how long it will be able to do this is questionable.

I always say that a sign of a translation's acceptance is it's availability in various study Bible editions. Currently the NASB is available in more study editions than at any point in its history. NASB versions of the MacArthur Study Bible and the Scofield Study Bible have been recently released. And the NASB is also available in the Life Application Bible, Zondervan's NASB Study Bible (the equivalent of the popular NIV Study Bible) and Student Bible, Ryrie Study Bible, Inductive Study Bible from Kay Arthur, and a host of other editions.

One final trivial point, this translation is officially known as the New American Standard Bible (NASB), not the New American Standard Version (NASV). I occasionally see this error, even in print. And the worst offense was an entire edition of the Open Bible, published by Thomas Nelson a few years back that had the incorrect designation printed on the spine.

How I Use the NASB. Currently, I use the NASB in my personal Bible study, usually along with the original languages and a more contemporary translation such as the HCSB, among others. I rarely get to go to a class or study led by others, but when I do, I often carry the NASB because that's where most of my handwritten notes are! As mentioned, I am no longer reading from the NASB in public except on rare occasions. I still find it extremely valuable for personal use.

What Edition of the NASB I Primarily Use. I currently use a burgundy wide-margin, Side-Column Reference edition in genuine leather (ISBN 0910618496) published by Foundation Publications (the press of the Lockman Foundation).

For Further Reading:

- David Dewey, A User's Guide to Bible Translations, pp. 156-157, 173.

- Lockman Foundation NASB Page

- List of Translators (scroll to bottom of the linked page)

- Bible-Researcher NASB Page

- Better Bibles Blog NASB Page

Feel free to suggest other links in the comments.

Update: Since first posting this entry, I received a reply back from the Lockman Foundation in regard to my question above regarding the 4th Aim:

Dear Mr. Mansfield,

Thank you for contacting the Lockman Foundation.

In response to your inquiry, I have found the following information in our files:

It was F. Dewey Lockman’s policy that in translating the Word of God, praise should not accrue to men, but that all praise should go to the One of Whom the Bible speaks.

For this reason the names of the translators in the past had not been publicized. This thinking followed in the tradition which can be seen in the King James Version, the Revised Standard Version, and others; that a version could stand in quality on its own merits and not on the fame of the translators. However, The Lockman Foundation was continually asked, even years after Lockman’s death in 1974, for the names of the translators. So in the early 1980s, this policy was loosened somewhat, and an all-inclusive list of the translators was given out on a request-only basis. Over the next several years, The Lockman Foundation still fielded a large number of these requests so that a policy was finalized to address people’s curiosity and concerns as to the names of the translators. Thus, the names of the translators publicly appeared in several different distributed brochures detailing the NASB and were, soon after, accessible via our web site at www.lockman.org

As a general policy, The Lockman Foundation continues to not provide background information on their translators such as their individual degrees and positions held with respect to Mr. Lockman's wishes, specifically stated in the Fourth Aim in The Fourfold Aim of The Lockman Foundation: “[These publications] shall give the Lord Jesus Christ His proper place, the place which the Word gives Him; therefore, no work will ever be personalized."

Hope this information is helpful.

In His Service,

Xxxxxx Xxxxxxxxx

The Lockman Foundation

On deck: The New Living Translation (Top Ten Bible Versions #4)