Regarding Willow Creek's So-Called Repentance...

But I've been amazed at the inordinate amount of attention given today to statements made by Bill Hybels at last summer's Leadership Conference. The word repentance comes not from Hybels as far as I can tell, but from the title of a Christianity Today blog , Out of Ur, in a post called "Willow Creek Repents?" The statement that seems to be getting the most attention is this:

We made a mistake. What we should have done when people crossed the line of faith and become Christians, we should have started telling people and teaching people that they have to take responsibility to become ‘self feeders.’ We should have gotten people, taught people, how to read their bible between service, how to do the spiritual practices much more aggressively on their own.

Well, duh.

But let's be really honest here for a moment. If this is a statement of repentance, can I take the collective planks out of the church's eye for a moment, and simply be the first to say that just about every local body I've ever been a member of, and every church I've ever visited--Baptist, Methodist, WCA, Independent, whatever--should really be ready to repent of the very same thing?

Lot's of folks are having some kind of "Aha!" moment with Hybels' confession. But I would still venture to say that discipleship is seriously neglected (or poorly implemented) among churches of all stripes and variations. Program-driven ministry? The vast majority of evangelical churches engage in some kind of program- or event-driven ministry. At least Hybels/Willow Creek is willing to admit there's a problem.

Quest Bible Study Class Gets Mention from KBC

See "Sunday School New Birth Stories, part 3."

And if you're not in the class already, but if you're ever in the area, come join us at 10:30 a.m. on Sunday mornings.

Closed for Christmas (The Missing THIS LAMP Blog Entry)

In December of last year, the Lexington Herald Leader (the secular press, mind you) broke a story questioning why some churches had announced that they would not be open for services since Christmas fell on Sunday. Ben Witherington responded to it on his blog, and that's how I discovered it. Over the next few days leading up until Christmas, this issue would create quite a bit of controversy especially in evangelical discussions. However, This Lamp did not take part in the discussions because I pulled the article. Why?

Kathy and I had made the difficult decision to leave a church where we had been members, and I had been on staff on two separate occasions, for twelve years. This was a very difficult decision for us, but after moving to an entirely different county the year before, the commute--while not totally unmanageable--began to affect our participation, especially any mid-week activities. Further, after a number of years of reflection, I had grown increasingly convicted about the necessity of being part of a neighborhood church, not one that took me out of my local community (see my series "Rediscovering the Neighborhood Church" in the Site Index).

In leaving our former church for one literally within walking distance of our home, I tried very hard to emphasize to people at our former church that we were not leaving over disagreements or any of the normal, often petty reasons many people leave churches. I wanted to stay in good standing with our former church because I loved it and her members dearly.

So on December 5, 2005, a little while after posting the blog entry below which decried closing church doors on Sunday, I thought I should check the website of my former church. To my surprise, I saw that they, too, had planned to cancel Sunday services on Christmas. Out of propriety, because I didn't want anyone to think I was making a passive-aggressive stab at my former church, I pulled the post.

I believe enough time has passed that I can make the post again. By now I hope that no one has negative ideas about why we left our former church. And I hope that the issue of Christmas/Sunday services could be discussed in a time when it is not so much of a pressing issue. However, it is an important issue and will come up again in a mere five years. Rereading my self-censored post again, I realize that my mind has not changed a bit on this issue. We have five years to plan for Sunday Christmas services in 2011. Why not make this the most memorable celebration of a generation?

Does this make sense? Yes, the family is important, but do we promote the family OVER community worship on this Christian high day? What's next? No service on Easter because it also falls on the Lord's Day? The word Christmas itself comes from "Christ's Mass," one of the most significant worship days in the church's calendar.

I remember as a small child (probably about six-years-old) speculating that if Christmas ever fell on a Sunday (two holy days together), perhaps the Lord would return on that day. I didn't realize that this exact thing had already happened many times over the centuries. But even as a child, I saw the significance of these two days occurring together.

It makes you wonder if such a decision is best when even the secular media asks, "Why Do Churches Close on Christmas?" (Lexington Herald-Leader) [link is no longer active, but look here for reference to it]. As the church at large seems to be losing relevance in society, I'm not sure what kind of message this sends. Yes, we are promoting families. However, when a person becomes a disciple of Jesus Christ, he or she has a brand new family that goes beyond biology or legalities. It is a spiritual family--perhaps even more binding from an eternal perspective. What better time to spend with one's spiritual family than in worship on a Christmas Lord's day?

Further, Christmas and Easter have traditionally been the two holidays where church attendance increases. The people who don't come to church any other day of the year come on these two holidays. I have no doubt that in closing church doors on Christmas day, we will take some of these non-regular attenders by surprise.

I don't want to be legalistic here. And granted, this isn't as bad as R-Rated Bible calendars (see yesterday's blog); we are told in Col 2:16 not to judge one another regarding special days, but I do believe the decision to cancel services should be rethought. My greatest concern in church life presently is that of Christian community. As I've been reflecting on this for a long while now, community will probably be an ongoing theme in my blogs over 2006. In the changing nature of today's society, I believe that a primary gift the church can give the world today is that of a stable and nurturing community. Christmas on the Lord's Day should therefore be an extraordinarily special day of community and celebration.

Here's my suggestion for the future. Christmas falls on Sunday only about once every decade or so (no, it's not seven; leap year complicates things). Every few years when these two days combine, why not have a celebration commemorating Christ's birth that is extra special. Define that however you want, short of canceling services altogether. This special day can be planned well in advance and anticipated in excitement as it draws near.

There's nothing anti-family about spending Christmas with both family and church community. Ideally, these will be one and the same anyway. If not, the day has 24 hours like every other day and lots of opportunities for varied means to celebrate the Reason we set aside this very important high holy day.

The Video-Pastored Church: Is This Really a Good Idea?

So a couple of days ago, a different friend emails me a link to a local megachurch's* newsletter in which they've announced plans to start four or five new churches in the surrounding area. Now, I have no problem with starting new churches--especially in areas without a local church nearby. But that's not necessarily the method or motive of this particular church. They are concerned that some of their members drive more than 30 miles to attend church, so they are going to take the church experience to them. Moreover, although the worship will be live, the actual sermon will be delivered via video to try to create the same experience they would receive if they made the 30-mile trip to the main church's campus.

In my friend's email he stated, "I am curious as to what your thoughts might be on this... I struggle with the idea of having a video/TV pastor at multiple locations instead of an actual live pastor there." Well, personally, I have no struggle with this. I just believe it's a bad idea plain and simple, and I'll give you three reasons why.

1. The Video-Pastored Church Is Impersonal. The video-pastored congregation is "McChurch" at its worst. It's an attempt to package the ministry of one church and deliver a controlled experience to another location. There's no recognition for the needs of the local community. Rather, there's an assumption that if it works here, it will have to work there as well. How many of our churches have learned the hard way that the way the Spirit moves in one congregation cannot necessarily be captured in a bottle and made to work at another location? Yet the video-driven church is simply taking this attempt at reproduction to the next level, and the negative results of "packaged ministry" merely reaches new depths.

Plus, there's no room for a minister to change the "itinerary" of the service in response to the prompting of the Holy Spirit. I observed a truly amazing event at our church a couple of weeks ago. Our pastor stood up and said that during the worship experience, he felt convicted to abandon his prepared sermon so that he might address some critical spiritual needs our church was facing. As our pastor gave an impromptu message that morning, he preached from his heart--with no notes, but with great passion--for the same amount of time that he takes during a normal sermon. And it was moving; it was stirring. In the Sunday School class I taught afterwards, I told them that the message they just experienced may be one of the closest thing they might ever come--in our day and age--to an Old Testament prophet like Jeremiah standing up and giving a word from the Lord.

But could that ever happen in a video-pastored church? If we're going to receive our sermons via video, can't we just as easily stay home and have the experience in our bathrobes in front of high-def sets while munching on toast and slurping our oatmeal?

At the risk of sounding judgmental, I wonder about the motives of a video-pastored church. On one hand, such a move might simply be the desire to spread the ministry of one congregation to other regions, perhaps without thinking through all the implications. But on the other hand, I wonder how many of these video-pastored churches aren't merely an attempt for one church or one group of people or one minister to control the experience of their church plants? How much of this is, at the root, driven by ego? I mean is one particular pastor really significant/important/prophetic enough that we feel a need to replicate him in multiple places on Sunday morning? And if so, at what cost?

2. The Video-Pastored Church Is Non-Relational. It's this simple: you cannot pastor a church, nor can you be pastored through a video screen. There's no relationship between a pastor and his congregation in a setting like this. And it works on two levels.

I've been on both sides of the pulpit. Currently, I am not on a church staff, but I have been in the past and assume I will be in the future. For the person sitting in the pew (or the cushioned chair), there's not a personal connection to be made with the image on screen. There's something about having a gospel message proclaimed live in front of a congregation that cannot be captured on on video. Everything's always better in person. But it comes down to this: when my pastor is preaching on sin, it's a good thing for him to make eye contact with me now and then to remind me that I am a sinner like everyone else.

And the pastor himself needs to see the people to whom he's preaching. I can remember one of my first preaching experiences when I was in college, seeing a friend of mine weeping during my sermon. It shook me. What had I said? I asked her afterwards if I had offended her (it's one thing for the gospel to offend [1 Cor 1:23], but it's something else for me to be careless with my words). However, she said that my message had brought up some issues that she had pushed aside for a long time, and God showed her through my sermon that she needed to face these things.

I remember a similar experience a few years ago when I was interim pastor at a small country church. It was father's day, and I preached a typical "this is what a Christian father is supposed to be like" sermon. In my mind, I thought the sermon was a bit on the "lite" side. It was pretty much a feel-good message for a special occasion. But while I was greeting people afterwards as they exited the church, I noticed the organist sitting by herself on a pew. As I drew closer, I saw that she was quietly crying to herself. I asked her what was wrong and she replied that my message made her realize that there were things wrong in her home that she had simply been ignoring. I went to find one of her friends with whom I knew she was close, and the three of us talked for a while about some of these issues. But a pastor cannot do this if he cannot see his congregation. There may be a ministerial staff on site, but there's no room for the pastor's own immediate follow-up if he preached the message through video.

We are responsible for the messages we preach; we are responsible for the words that come out of our mouth. Hebrews 4:12 states that "the word of God is alive and active. Sharper than any double–edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart" (TNIV). When God's Word is proclaimed, lives are changed. The person proclaiming God's Word should be on site to respond in follow-up to the needs of the church members.

Certainly there's room and need for recorded messages, but these should never take the permanent place of personal ministry of a pastor to his congregation.

3. The Video-Pastored Church Keeps Someone from Fulfilling His Calling to Preach God's Word. Planting new churches is generally a good thing, but those churches also need strong leadership. I certainly realize that any satellite video-driven church will have to have some level of ministerial staff--some kind of under-shepherd(s)--to function. However, with pastoral ministry comes the calling to preach God's Word (2 Tim 4:1-2). For every church that delivers the Sunday sermon via video feed or DVD, there is a pastor who is not fulfilling his God-given calling to proclaim the gospel (Rom 10:14).

The church has just as much responsibility for equipping new preachers as our seminaries do--perhaps more so. A new church plant under the auspices of a larger, parent church is a perfect context for this to take place.

Look, outside of extremely rural areas and in mission regions that are largely unchurched, I don't believe people should drive thirty minutes to church either. I've written about this before (see links below). I firmly believe that part of the reason that so many people feel disconnected from their churches and their local communities is that they've separated the two from each other. There's a great communal value from living in the same community--the same neighborhood if possible--as your local church. In fact, I suggest that your church should be within five miles of where you live. Then you can go to church with your neighbors and have random points of contact with your fellow church members throughout the week. This helps create a feeling of community on multiple levels, not driving thirty miles in the hopes of creating community with a bunch of people you see only once a week.

As I've said here, planting churches is a good thing. But if we want to build community, if we want to impact our cities and neighborhoods for Christ, we must worship locally and we must minister and be ministered to locally. The video-pastored church--the video-driven church, if you will--is not the answer.

I had a conversation this past summer with an older mentor to me in ministry whom I've known for quite a long time. The context of our discussion was not this subject, but he said something that certainly applies. He told me, "What we need in our churches today are pastors who are good communicators--without the ego--and have good people skills. It's that simple." I agree. And further, I agree that these pastors need to preach in person, not via an impersonal video screen.

*I am purposefully not naming any individuals or churches in this post. Although I disagree with video-pastored churches, I don't deny that the churches and the ministers themselves are performing valuable ministries and changing peoples' lives in their contexts. I have no desire to detract from the good that these ministries are doing. I just believe that in-person teaching and proclamation of the gospel is a much better idea.

Related Viewing:

• Rediscovering the Neighborhood Church, Parts One, Two, Three and Four

• Hank Hill and the Local Megachurch

Confession: Good for the Soul; Bad for the Reputation

Let me be very honest here. Is it just me or does what often passes for accountability in the church leave you feeling squemish as well?

In the past through various church settings, I've been partenered by a third party with a small group other men (usually two to three) with whom I'm supposed to meet regularly and be accountable, especially about our struggles and failures. But such pairings tend to almost always feel artificial to me. Maybe it's my personality, but I'm just not going to open up and spill my guts to someone whom I don't already consider a close friend. And by a close friend, I mean someone whom I've known for years and has a track record of being faithful and when need be, confidential. But even if I was grouped with very close friends with whom I have trust, would it still be necessary to talk about everything? I've heard of men's accountability groups that have the men ask each other about the state of their sex lives with their spouses. Pardon me, but is that anyone else's business besides the husband and wife in question?

I remember another setting a few years back in which a friend confided something to me from his past. He said he needed an accountability partner. On the surface, that would be fine, but there was no immediate context for his confession. This was something in his past that he had dealt with. It wasn't a current struggle. It wasn't something I really needed to know. So why did he tell me? Well, I was slow at the time, but later I realized that he made this confession, not because he wanted my help, but because he thought I was engaged in some kind of equivalent sin (which I was not--he had misread some circumstances he observed without asking me about it). He assumed that by "opening up" to me about his struggles, I would just naturally confess my sin to him. Of course, I couldn't confess what he wanted me to, simply because it wasn't true. But the artificiality of the whole "meeting for accountabilty" made me feel compelled to confess something. So I told some "lesser" sin from my past which wasn't all that damaging, but later I just felt stupid over the whole situation. And I've never bothered to correct my friend's suspicions about me. I guess he can think what he wants.

That doesn't mean that I'm not open to talking with people about serious problems and acting in a helping and supportive capacity. There's also a very needed role that something like a support group can play in times of crisis or struggle; and in those situations, the lack of personal history with others in the group can be of benefit. And it's one thing if I'm in a pastoral or counseling type role. I've been on church staffs, I've been a chaplain, and I'm often a listening ear for those in need. I can take that position seriously and try to help someone get past his or her sin or time of crisis. And I don't mind opening up to someone else when I have a problem if that person is someone with whom a certain amount of trust has been established. But I just don't get anything out of the "You tell me your sin and I'll tell you mine" mentality that often passes for accountability groups.

We all remember that Jimmy Carter said that he had "lusted in his heart" after other women. Well, we've all done that, but do we need our president making himself accountable to the whole nation over something that personal? (Maybe, in hindsight, another president should have made himself more accountable on this type of issue.) But regardless, no one listened to Carter's confession with a sense of deep concern. We raised our eyebrows and many chuckled within themselves. Carter's statement became the butt of jokes on late night television. I feel like we need discretion regarding what we confess to others, especially in a public forum.

Confession: good for the soul, but bad for the reputation.

Regarding the article Matt linked to... I too cringe at the idea of having someone put $10 in a jar because he or she sinned again in a particular area. Forget that--it screams of legalism; plus, who has enough money? I'm glad the writer of the article (I don't even feel comfortable mentioning his name in light of what's coming) has a group to which he can admit lusting after another woman right before his wife gave birth to their most recent child. But he didn't just confess it just to them (and his wife); he had to go and tell all of us as well. I don't know him--but I don't need or want to know such private things about him. He's shared this with the world--and his church. If I ever meet him--which I doubt I will--I might be thinking about his confession. And I know that pastors are supposed to have a certain level of transparency to relate to people, but is it good for him to tell his whole congregation (which he did by writing the article) that he was lusting after another woman as his wife was about to give birth? I want to take him aside and say, "Hey, buddy--keep that to yourself."

None of us can throw stones when it comes to sin. I realize that. But is it a good idea to be so open about our sin?

Somehow there just seems to be a lack of discretion and a lack of prudence in our motivation to confess stuff to each other these days. I have no doubt that the medieval church's confessional was quite therapeutic for a lot of folks. Go in and talk to a person who can't look you in the eyes and get all the nasty stuff you did off your chest and get offered some kind of penance for it. Done! Past is past--bygones. Yes, I know that confession was abused, but it probably started with good intentions and purer motives. And no doubt, Protestants and the modern world at large have replaced the confessor-priest with the psychiatrist or counselor, probably not always for the better. But "Average Joe" in my church is neither priest nor professional counselor, and I don't feel compelled to have to tell him on a regular basis where I messed up in the last few days.

I realize that James 5:16 says "Therefore, confess your sins to one another and pray for one another, so that you may be healed" (HCSB). However, I don't care for what I perceive as artificiality in the requirement for regular meetings of accountability which usually revert to, "Well, tell me your sins from the past week and then I'll tell you mine." No, I don't think so. And then you know what happens. Your name is mentioned in the next prayer group that your accountability partner attends. "We need to pray for Rick. I can't tell you why, but we really need to pray for him." And then someone concerned pulls him aside later and asks "What's going on with Rick?" The response is then, "Well I really shouldn't tell you this, but... ." Forget it.

Don't think I'm an island. Besides my wife Kathy, who is my best friend, I do have a few of close friends with whom I could confide just about anything--and have--in the case of a major struggle. In fact, I meet with them on a regular basis, but not with an agenda to confess our sins (though sometimes we do). We meet because we are friends and brothers in Christ and we talk about everything--the public, private, spiritual, and earthly. But our ability to confide in each other comes from years of friendship and trust.

When it comes to confession, in addition to James 5:16, I also want to take 1 John 1:9 seriously--"If we confess our sins, He is faithful and righteous to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness" (HCSB). But that confession remains between me and God. And for the large majority of what I need to confess, that's where it will stay.

Hank Hill & the Local Megachurch

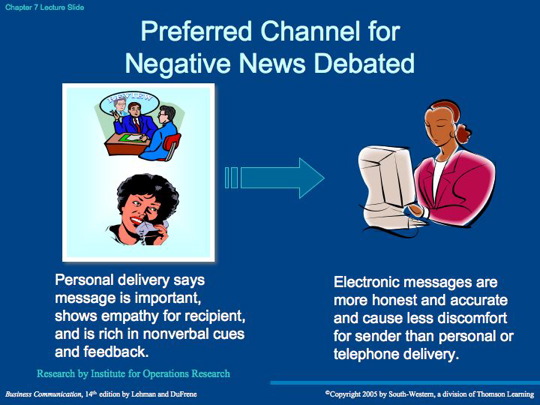

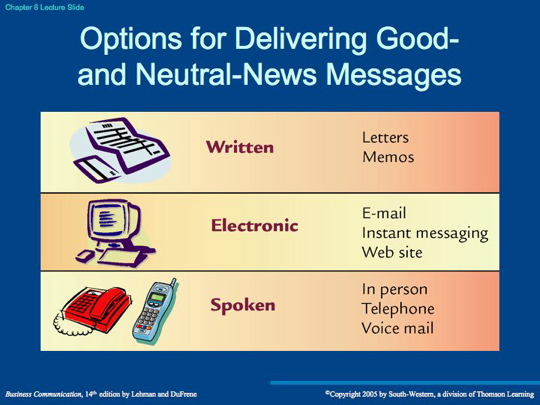

Basic Principles of Communicating Negative Information

For instance, negative information (bad news) is best communicated through personal means. Face-to-face is ideal, but since that is not always possible, sometimes a telephone call is appropriate.

Email as a method of delivering negative information usually benefits only the sender and does not communicate empathy for the receiver. On the other hand, good news can be communicated through any means.

If this makes for good business practice in the workplace, why would we EVER want to communicate negative information via email (or other impersonal forms) in the church?

Rediscovering the Neighborhood Church, part 4

Barger was fairly critical of the megachurch as an entity that does not foster community. I'm going to try to straddle a fence here and not be quite so harsh on the megachurch as some are who share my perspective. I do not desire to disparage other ministries. One of the most common criticisms of megachurches is that their services are geared more to entertainment. To be fair, it's hard to create interactive, communal worship in stadium seating. It's also said that megachurches are more of a boomer phenomenon. I guess we'll see if that's true as all the generations get older. My hunch is that the Willows and Saddlebacks of the world were not created by human intention. Such enormous ministries grew unexpectedly under the feet of their leaders. I have grown through the writings and teachings of Warren, Hybels, Ortberg, Strobel, and others. I have gained insights at attending Willow's Leadership Conference more than once.

However, having said all that, I believe I can safely say that I don't want to be a part of a megachurch. And like Barger, I'm skeptical that it's the best thing for our communities as they often attract people who drive considerable distances to attend. From my perspective, instead of 20,000 folks meeting at a megachurch, I'd much rather see 80 neighborhood churches of 250 or so members spread throughout a city, especially if these churches can work in association with one another. I have been on church staffs and at times like right now, have been simply an active member. As a member, I do not desire to be in a church where I can't go to lunch with my pastor or other staff members every now and then. And I certainly don't want to be a member of a church where the pastor and I do not know each other. When that happens, the pastor is no longer in a pastoral role at all. Community has to take place from the top down.

How large is too large? Well, to put a number on it is to promote legalism. I don't want to do that. But when a church gets so large that members consistently look unfamiliar to other members it may be approaching those wider limits. If my pastor can no longer pastor me, or if I as pastor can no longer act as shepherd to the congregation, the size has become too large. Perhaps churches should consider all their options when they outgrow a particular site. The worst thing a church can do is relocate a significant distance away from an original site because of what its absence will do to the neighborhood community it leaves. Some will never be able to relocate, and the relocated church simply creates a spiritual vacuum for the abandoned community.

When a church begins to outgrow its present site, the best option may often be to send some of the best talent and the best leadership to a new church plant on the fringes of where the current membership lives thus creating a new neighborhood church. That doesn't mean simply creating a satellite church across town where members are commuting great distances and are not plugged into the local neighborhood. At the very least, members should be encouraged to eventually move into the neighborhood surrounding the new church, thus creating an indigenous mission force. And it also doesn't mean building a church in the backyard of a sister church. Although the idea of the parish is not official with most Protestant denominations, we should be respectful of ministries that are already ongoing in a particular neighborhood.

I wrote at the beginning of part 3 that many of us have gone about choosing our churches in the wrong way. We've sought out the biggest church, or the church with the most dynamic preacher, or the church with the most programs, while often neglecting the church that might be right within our own neighborhood ministering to the very people we should also be ministering to. I'm not suggesting that anyone leave their current church. But I am suggesting that in the future, if you find yourself looking for a church home, you should start with the general principle of which church is closest to you geographically. This will enable you to have those "random unplanned, unstructured encounters" with each other that Barger talked about. You will be able to be more involved, even in midweek ministry, because commute time is not an issue. And more importantly, you will see the same people at church that you see next door, and if you don't see them at church, you can be confident that you have the same interest in their well-being that your church does.

While I don't recommend that you change church membership, I might recommend that if you plan to stay at a particular church for the indefinite future, that you make plans to move closer to your church. How close you should be? How far is too far? As a general rule (and there are exceptions), I would say that walking distance is ideal, but a commute that is more than five miles is too far.

And don't live in an area solely based on proximity to work. I would recommend that it's better to live closer to your church than to work. A workplace often changes, but church life should be more stable. If, however, you can have all three together as my wife does, you are even better off. In fact, if you move to a new area, you have the option of finding a healthy church and then moving into its surrounding neighborhood.

Are there exceptions? Certainly. I'm not suggesting that the five-mile rule applies as significantly in rural communities. I grew up in a town of 20,000 people where there were a handful of prominent churches spread over town. All the advantages of a local neighborhood church would have applied to any of those churches. Also, there are still some places in our country where there aren't as many churches. Obviously, denominational loyalties will be a factor to many as well. I certainly understand that. I don't think this necessarily applies to the student or someone in an extremely temporary situation. Are you part of a church plant? Make efforts to move into the neighborhood of the new church within a reasonable amount of time. And pastors should gently encourage members to live within close proximity and question those who drive an extreme distance.

But I don't believe we should shop for churches the way we shop for a new car. The fact that you don't like a particular pastor's preaching style, or that the message didn't speak to you, is a really poor excuse. An "unfriendly church" isn't really a good excuse either. Perhaps you are being called to go to that "unfriendly church" and be friendly to all the visitors who might otherwise be turned away and thus set a good example for the current membership.

Certainly some might suggest that the church is called to be witnesses "in Jerusalem, Judea and Samaria, and to the remotest parts of the earth" (Acts 1:8). I agree with that. But a church's Jerusalem is the local neighborhood, it's parish, if you will. The people who live there--members, potential members, and those who will never be members--are a church's primary ministry obligation. Churches working with other churches in association in a community can be the Judea and Samaria. And denominations and mission organizations can reach the entire world through the people and resources the local churches provide.

My desire is not to be legalistic, but rather to foster community. I am suggesting general principles as a corrective to our modern dichotomized communities of neighborhood and church. I believe it's time to encourage people to bring these two together again as one community. I'm confident that one of the ways we can really reach people--one of the ways we can really reach the lost--is to offer them a stable, foundational environment through our churches. We can offer them a new family to help complete the turbulent and often dysfunctional families that exist behind the closed doors of our neighborhoods. We can offer them community in a way that no other affiliation can--one that is immediate, and powerful, and eternal.

Rediscovering the Neighborhood Church, part 3

In part 2 of "Rediscovering the Neighborhood Church," I brought up a schism that's been created by living in a neighborhood that's different from our church's neighborhood. This is a new phenomenon, the result of an increasingly mobile society that thinks nothing about driving across town to go to the movies, or to go shopping, or to go to school. So why not church, too?

In my previous discussion of this topic, I spoke of the disconnect that Kathy and I felt as we left our neighborhood, town, and even county, and drove elsewhere for spiritual community. It made no sense. We struggled with this for months, but we finally made the hard decision. In spite of the fact that we belonged to a great church, a church where we had been for a decade, a church where I had been on staff twice, we made the decision to move our membership to a body of believers in the town where we now live. In fact, we joined a church that is within walking distance of our house.

I'll never forget the first Sunday we visited, which incidentally, was a few weeks before we actually joined. Kathy and I were immediately welcomed by familiar faces. We saw people that were from our own neighborhood, who lived down the street. We were greeted by Kathy's co-workers. Children whom Kathy teaches ran up to her with smiles, yelling, "Mrs. Mansfield! Mrs. Mansfield!" I felt the immediate spiritual bond between geographic community and spiritual community. And for Kathy, there was added the third sphere of the workplace. I really don't think I had experienced that since my early twenties, since before we moved away from home. Before that day, I would have guessed that such a feeling of community was no longer possible in our modern world. But I was wrong.

Think about it for a minute. What missionary would try to reach one village, but live in a different village? That wouldn't happen very often unless he was the only missionary for miles around. So why do we do this with church? In every home in which I've ever lived during my adult life, I've felt like God placed me there for a purpose--to minister in that local neighborhood community. And yet, at the same time, every church sees as its mission to reach the people in its surrounding neighborhoods. For me, the two were never the same. Until this last year, I never realized the disconnect I was creating in my life and my church involvement. It's too much. It spreads a person too thin. Under such a self-imposed dichotomy, I don't have the help of a local body of believers to help me minister in my neighborhood. And just as bad, I don't have as much of a vested interest in my church's local neighborhood as I ought to. In fact, although I was very involved in my former church over the last decade, I had very little to do with the church's local neighborhood outside of the occasional "First Impressions" gift to new residents. I am ashamed to admit it, but I was never completely sold on my church's mission to reach the surrounding community. It wasn't something that I was conscious of though. I see it now because I've reflected on this, and I realize it was because I didn't live there.

A few months back I listened to a missionary home on furlough talk to a group of us who were her friends. She said that one thing she realized since being out of the country is that the church in the United States is too disconnected. We're traveling here and there, and we're not invested in our neighborhoods and each others' lives. She said one thing that Catholics had over Protestants was the old idea of the parish. Barger said the same thing in my quote from part 1. The parish. The Catholic Church has understood this for centuries. A region is broken up into parishes, and by and large members go to the church in their parish, in their local neighborhoods. They have community that transcends the church's walls because they see each other on their neighborhood blocks when the go for walks at night. They run into each other at the grocery store. The kids go to the same schools.

Protestants have never learned the lesson of the parish. In our desire to be independent, we build churches wherever we want--often in the backyard of an existing church. We put ourselves in consumer mode and "shop" for the church which we think will suit our needs best oblivious to the needs of the actual geographic community in which we live.

You know, I had a clue about this a few years ago. For a number of years, Kathy and I lived in a very urban neighborhood just about half a mile from downtown Louisville. It was a mixed neighborhood of blue-coller families who had lived on the same streets for two or three generations. Then, there were newcomers like us who were living in the remodeled shotgun houses. Tradition and trendiness were side by side. One thing I noticed soon after moving in was that the folks who had lived there all their lives, would go outside in the evenings and sit on their front steps, yelling conversations back and forth to one another across the street. So that we could do that, I pulled up the patch of ivy that was in front of our house (never liked ivy--a mosquito trap in my opinion) and laid down faux-brick patio stones and put a glider swing on top. Many nights we joined in the evening neighborhood cross-street conversations. But not often enough. There were many to minister to in this neighborhood, but we were involved in a church clear on the other side of the city in a neighborhood with a whole different mix of inhabitants.

Ironically, there was a church--a very small Baptist church--often pastored by seminary students, right on our block! They had a clothing closet that was open every Thursday, but they were a spiritual lighthouse in that neighborhood in a variety of ways all week long. I remember Kathy being invited to a baby shower for one of the young girls in our neighborhood held at that little church. This particular girl was pregnant without a father in the picture, again. Of course, regardless of the young woman's choices, her circumstances weren't the soon-to-be-born baby's fault. It wasn't the fault of her other toddler. Kathy was touched at how the church reached out to that young girl and her family. Despite her situation, the church saw to her physical needs and hoped and desired to tend to her spiritual needs as well.

Now, I don't relate any of that to diminish the church experience I had during those years. I wouldn't trade anything for the friendships I made, the ministry that I was involved in, and the help the church gave Kathy and me during some very difficult times. But now that I've been awakened to this issue, I never want to separate my neighborhood community from my church community again.

I have talked to so many people in the last year or two who tell me they feel disconnected from their church, often after being members in a particular church for a number of years. And I've talked to couples, often young couples, who can't find a church, but desperately desire a place where they can feel like they belong. I'm not saying that joining a neighborhood church will solve every difficult issue of fellowship facing the church today, but it's a start in the right direction--a very powerful start.

Rediscovering the Neighborhood Church, part 2

But our struggle wasn't new. This was merely a new revelation about something that had been bothering us for a while. There were a number of factors involved.

I had become very disturbed over the previous year or more that my involvement at church, my church life, seemed much less central than it used to be. Church had always been a primary force in my life. Mom says Dad insisted that I go to church beginning when I was only two weeks old! Even during semi-rebellious teenage years, the church provided a solid ground in the midst of my self-induced chaos. As an adult I had a seminary degree and had been on a number of church staffs--so why was church less a part of my life than it had been in the past?

Well, it didn't happen overnight. Kathy had taken a position at the elementary school in Simpsonville, Kentucky, in 2003 and we eventually decided the best thing to do was to move to Shelby County, and I would be the one to commute back into Jefferson County for my work. Most of the earlier part of my life had been spent living outside the limits of Ruston, Louisiana, a town of roughly 20,000 people. Kathy and I moved to Louisville, Kentucky in 1991 and for well more than a decade lived in a very urban setting, at one point living only about half a mile from downtown itself. My mother-in-law had jokingly started calling me "City Boy" because I took to the urban setting and lifestyle so quickly and so well. Moving to Shelby County was almost like going back to my childhood. In such a rural setting, things moved much slower here. For the first few weeks, as I drove out of Louisville and headed to Simpsonville, I felt like I was leaving for vacation every evening.

Kathy and I had been part of the same church for practically a decade. I had been on staff there two different times. When we moved, we never thought twice about the distance we were putting between ourselves and our church. In practical terms, it did not seem all that much further than when we were driving across Louisville to go to church. People commute everywhere in urban areas--work, school, and even church. What's the big deal with a commute?

Well, it did turn out to be a big deal. If we hit traffic at the wrong time of day, we could spend up to an hour round trip just commuting. This wasn't an issue so much on Sunday; but often, with our cramped schedules, it made getting to midweek activities difficult. And there were psychological barriers, too. Maybe the actual miles weren't much further than driving across Louisville, but there was something about leaving one town, leaving one county and driving to another that sure made it feel much further.

The most important factor, though, was what was happening to us on a communal level after we moved. We were meeting our neighbors, and we were starting to interact more with the local town. We weren't just camping out for a while while Kathy had this particular teaching "gig." Rather, we were settling in to the community. Strange faces became familiar, and then we found they had names. I began to ask myself whether someone who lived down the street would be willing to visit my church in another city, in another county if I were to invite him? And I really began to struggle with that. I counted one day and realized that we passed seven churches on the way to our church--and that was before we even got on the interstate.

I had one of those light bulb moments. I realized that in our increasingly mobile culture--especially in urban areas--we as Christians have gone about choosing a church body in a very wrong way. And in doing so we've separated the community in which we live from the community we find in our churches. Historically, such a schism is a new phenomenon. Traditionally the two communities have always been synonymous. I believe this unnatural division is a very dangerous thing. Not only has it weakened the church, but I believe it has led to a growing feeling of disconnectedness I'm hearing about from so many Christians, even while they are in the midst of very sound and otherwise healthy churches.

In part three, I'll discuss this problem in greater detail and conclude this series by offering some practical solutions.

Rediscovering the Neighborhood Church, part 1

Ken Myers of Mars Hill had interviewed Ms. Barger regarding a book she had written for women. However, he included a second part of the interview on the CD's bonus track, entitled, "Why the Foodcourt at the Local Megachurch Isn't What Our Neighborhoods Need." That phrase actually never came up in the discussion, and must therefore be something that Myers thought of when he labeled the tracks. A number of people whom I've let listen to this interview get caught up on the megachurch issue, especially if they want to defend the idea of a megachurch. That's not my point in posting this here. I'm primarily interested in what Barger says about the place of the church in the local (literally local) neighborhood/community.

I have transcribed the portions of the interview that I thought were of value for my purposes here. If you would like to hear the interview in its entirety, it is available for listening online. Here is the transcribed excerpt that I think is most significant:

When I say community and we talk about community--local church community--I mean local. Local is not getting in the car once a week to drive fifteen miles across town to a megachurch that’s got five or six thousand people where you spend two hours there and go home.

That is not a community. That is an association. When I say community and I’m talking about local community, I’m talking within a very small geographic space. Because we are people who live in a small geographic space ... And I think it’s sad that we have gotten away from the neighborhood church, that people are driving miles all over to go to a huge church for two hours. The only way the church is going to be a redeeming community, active in the lives of people is when we get back to a very local model--smaller churches closer to where people live and work. That way we can integrate all of life.

I think it’s that medieval idea of the parish. I think that’s what we have to go to. I don’t think the megachurch is going to get us what we need. I think we need smaller and closer communities. I don’t think it’s [the megachurch] a good thing at all. I think it’s about performance and entertainment. And it’s not about pastoring and relationships and being close to where people live, where they sleep. I think the megachurch will never be able to do that. Because even if they say, "Well we’re going to have small groups," well, if you still have to drive ten miles to go to your Tuesday night small group meeting for another hour...

We need it [local church community] to be close enough that you have these kinds of random unplanned, unstructured encounters with each other.

We’ve got everything working against us. We’ve got sprawling suburbs. We’ve got automobiles that let us go anywhere we want to go. We’ve got communication--email and telephone--that gives us the illusion that we are still connected to each other. And we have forgotten the real need for physical presence.

In part 2, I want to look at the issue rediscovering the value of the local neighborhood church. I will interact with some of what Barger says, but primarily I want to focus on my personal journey and in then in part 3, offer some suggestions that just might help believers get connected with one another again.

Life Together (Bonhoeffer)

by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Current edition: © 1979, Harper Collins Publishers

As noted, the book is fairly short--only 128 pages. It's divided into five sections:

1. Community

2. The Day with Others

3. The Day Alone

4. Ministry

5. Confession and Communion

In the first section, Bonhoeffer lays out a theological foundation for Christian community beginning with a quotation from Psalm 133: "Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unit!" (v. 1). And although starting from an Old Testament reference, the source for Christian community is demonstrated to be in the person and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Christian brotherhood is not an ideal which we must realize; it is rather a reality created by God in Christ in which we may participate. The more clearly we learn to recognize that the ground and strength and promise of our fellowship is in Jesus Christ alone, the more serenely shall we think of our fellowship and pray and hope for it. (p. 30).

In the second section on the day with others, Bonhoeffer describes how the day should be started when living in community--what he calls common devotions. These common devotions are broken down into Scripture reading, singing together and prayer. Bonhoeffer creates a guide as to how each of these components can be facilitated allowing them to work together. Further, such common devotions should be done before breakfast, what he calls "the Fellowship of the Table." Bonhoeffer goes on to describe how this benefits the days work, and his assumption is that the community or family will be able to join together again for a meal at noon and the end of the day.

Lest anyone should become dependent upon the community as the sole avenue of the spiritual life, Bonhoeffer also has a chapter on individual disciplines, "The Day Alone." See my previous post for a quotation from this chapter where he points out the danger of neglecting community or spending too much time in community. As with all things, there must be a certain amount of balance or moderation. Bonhoeffer goes on to discuss the importance of the individual believer's need for meditation on the scriptures, prayer and intercession.

I was especially intrigued by Bonhoeffer's chapter on ministry. This is without a doubt a chapter that every pastor and Christian counselor should pay close attention. Bonhoeffer was probably writing primarily with the pastor of a church in mind, but I believe his message applies to anyone in a position of spiritual leadership. He has a section entitled "the Ministry of Holding One's Tongue" and another on "The Ministry of Meekness." These sections serve to remind the person in spiritual responsibility of the privilege that it is to work in service to the Christian community. He follows these with a section on "the Ministry of Listening." Here, Bonhoeffer states the following:

The first service that one owes to others in the fellowship consists in listening to them. Just as love to God begins with listening to His Word, so the beginning of love for the brethren is learning to listen to them. It is God's love for us that He not only gives us His Word but also lends us His ear. So it is His work that we do for our brother when we learn to listen to him. Christians, especially ministers, so often think they must always contribute something when they are in the company of others, that this is the one service they have to render. They forget that listening can be a greater service than speakingl (p. 97, emphasis added).

I was also touched by Bonhoeffer's words in his section, "The Ministry of Bearing": "It is only when he is a burden that another person is really a brother and not merely an object to be manipulated" (p. 100).

In the final section on confession, Bonhoeffer seemed to be way ahead of his time on this subject. Way before Promise Keepers or related accountability groups, Bonhoeffer wrote, "He who is alone with his sin is utterly alone" (p. 110) and "If a Christian is in the fellowship of confession with a brother he will never be alone again, anywhere" (p. 115). Of course, he really wasn't introducing anything new at all, but rather reintroducing the value of confession (perhaps lost in reaction to the Catholic Church after the Reformation) and the reality that the average person in sin needs only forgiveness from on high and the firm and loving support of close friends.

If you've ever read The Cost of Discipleship, this books seems to be a natural follow-up, although it is very different in both tone and scope. According to the introduction, Bonhoeffer wrote both books during the same period in his life, so the one naturally flows into the other.

The book was especially meaningful to me because the two areas of concern I have for the church today--and the two areas where I feel I can most contribute--are discipleship and community. These are not something the church has always done well, but something we are called to do, and when done well can be a dramatic foretaste of eternity to come. From conversations I have had over the last year, and from ongoing conversations, community seems to be one of the most sought after, and yet the most elusive gifts the church has to offer. However, if made a priority, community can be a steadfast offering from the church to an ever-changing world. I will be writing more on this subject, including my own journey, in this new year.

One final note. I obtained my copy of Life Together used. There is a personal note written in it, not inside the cover where you might expect it, but on the page facing the first chapter. It is dated September 3, 1998. It reads, "With the prayerful hope that you will find and join and build Christian community. Love Dad." What does it mean that a little over seven years ago a father placed this book in his son's hands and now his son doesn't have it anymore? I don't know. It somehow seems a bit sad. But maybe it can be encouragement for all of us concerned about such things to help fulfill this anonymous father's wish.