Proverbs 22:26

“Don’t gamble on the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow,

hocking your house against a lucky chance.”

(Prov 22:26, The Message)

Follow-Up to the Message: What Is the Proper Use of a Bible Paraphrase?

A month ago, I wrote a blog entry entitled, "Is a Paraphrase in the Eye of the Beholder?" that wrestled with the sticky issue of defining a paraphrase in distinction to an actual translation of the Bible. In that entry, I referenced David Dewey's definition of a paraphrase from his book A User's Guide to Bible Translations, but found that his definition wasn't as all-encompasing as what I would like. Dewey paid This Lamp a visit and posted some very helpful insights in the comments section:

The line between paraphrase and a free translation is hard to define and is really quite subjective. But there is a spectrum going from literal through free to paraphrase though different people would place the 'borders' in differing places. I would add that paraphrases are less consistent in their rendering than free translations. I remember talking to Barclay Newman, chief translator of the CEV, who says translation is all about rules, rules and more rules. The CEV and GNB are less paraphrastic than the LB or the Message because the former, though very free, do follow certain rules more consistently whereas the latter are more idiosyncratic.

I feel Dewey's comments are extremely helpful here by generally stating that a translation is bound more by rules of translation while a paraphrase is tends to be more what he calls idiosyncratic. Perhaps we say that a paraphraser has more freedom in his or her renderings.

The Question of Use in Worship. A question that has come out of the comments section from my entry on The Message relates to the proper use of a paraphrase. Jeremy Pierce was surprised that I have used the Message for "public reading" in place of a more traditional Bible translation. Further, Peterson himself seems to discourage such a practice, according to Jeremy, because he doesn't want his work confused with the Bible itself. In a 2002 Christianity Today Interview, Peterson said,

When I'm in a congregation where somebody uses it [the Message] in the Scripture reading, it makes me a little uneasy. I would never recommend it be used as saying, "Hear the Word of God from The Message." But it surprises me how many do. You can't tell people they can't do it. But I guess I'm a traditionalist, and I like to hear those more formal languages in the pulpit.

I suppose that part of Peterson's sentiment comes from his own genuine humility. It's understandable that he would be uneasy about having his rendering of the Bible proclaimed as God's Word. Up until recently, most Bible translators remained anonymous and I can see why. It's a weighty responsibility to even teach or preach God's Word, let alone translate it for the use of others.

Is a Paraphrase of the Bible a Bible? But let's back up to another question. Can a paraphrase of the Bible fairly be called a Bible at all--or is it merely a kind of commentary? I know that some people say absolutely not regarding the question of whether a paraphrase is a Bible. But what about the publishers themselves? There are three major modern paraphrases of the Bible in modern English: J. B. Phillips' New Testament in Modern English (revised 1972), Kenneth Taylor's The Living Bible (completed 1971), and Eugene Peterson's The Message (completed 1992). Of these three, only The Message is in widespread use today.

Early editions of Philips NT and The Message came without verse numbers that seemed an attempt to distinguish them somewhat from being thought of as actual Bibles. But later, publishers included verse numbers in both. I don't think The Message had verse numbers until the Remix edition of 2004, but the numberings had already existed for a few years prior for use in Bible software programs. The Living Bible had chapter and verse designations from the very beginning.

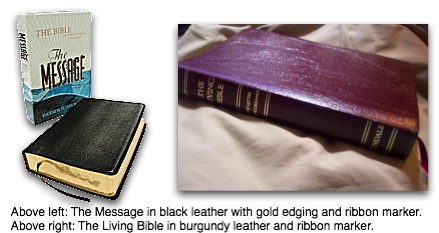

Further, the pictures at the top of this entry depicting leather-bound copies of The Message and The Living Bible were selected with s particular motive. When a publisher begins marketing a Bible paraphrase with leather, gold edges, and ribbon markers, it can only mean one thing: these editions are intended to serve as personal Bibles, possibly even primary Bibles. To me, the message (no pun intended) is unmistakable.

To answer my own question, I would say that yes, I consider a paraphrase of the Bible to be a "real" Bible (but I'll qualify that statement in a moment). When I designated a title for my series on my favorite Bibles, I specifically used "Versions" because I believe a Bible version encompasses both translations and paraphrases. Even the Septuagint seems paraphrased in a few places, and no one would doubt it's place as an ancient text representing God's Word. And "representing" is the key thought here. No version of the BIble--translation or paraphrase is God's Word itself. They are merely a vehicles for communicating God's Word.

And here's the qualifier to my "yes" in the above paragraph. As I have stated before, although I would encourage the use of a paraphrase like The Message, I would never recommend it as a primary Bible for study, but rather as a tool alongside an actual translation. However, some do use paraphrases as their primary Bible. A whole generation of church-goers carried those green hardback Living Bibles every Sunday, and I know of a few older members at my church who still do. I regularly see young people carrying copies of the Message to church.

I certainly understand why people do this. Often paraphrases communicate to these readers in a way that they perceive they understand God's Word better than with actual translations. I don't think it's wise to berate people for the Bible they're using. Surely it's better for someone to read a paraphrase of the Bible than no version of the Bible at all. But it's also important to let people know the benefits and cautions of a paraphrase.

The Benefits and Cautions of Using a Paraphrase. The benefits are clear. Paraphrases communicate God's Word in a very easygoing, contemporary style that may enhance understanding of the Bible. Often, it's easier to get someone who's never read the Bible to read a paraphrase first before picking up an actual translation. Sometimes children respond better to a paraphrase (although I like the Good News Bible best for children) than an actual translation. My experience reflected this when as a child often I couldn't understand a passage in the King James Version, but was able to cross-read it in the Children's Living Bible given to me by my grandmother. Teenagers might respond well to a paraphrase, too. When I used to teach high school Bible, I often used The Message for our reading of longer OT passages (but I did not allow them to use The Message as their Bible for classwork). Further, I thoroughly enjoyed reading through the Message in my devotions a few years back, and recommend it to anyone for that use. It took me longer to get through The Message than any previously read version of the Bible because I slowed down to "hear" the words and I tended to reflect on them more.

But there are also cautions. There's no such thing as a committee-based Bible paraphrase to my knowledge. Therefore, any Bible paraphrase is the product of one individual (such as Phillips, Taylor, or Peterson). As godly and as genuine as these men are, they're still human and can make mistakes. The benefit of a committee-based translation lies in the checks and balances of many eyes upon the work. Further, while all translations of the Bible include some amount of interpretation, paraphrases--which by nature have very free renderings--are simply the most interpretive of any kind of Bible version. Since the paraphrase is the work of one individual, that means one mind is interpreting the text for the reader. As masterful as I believe The Message speaks in contemporary language or as clever as I think Phillips NT renders the text at times, I never let myself forget that I'm receiving one perspective on the biblical message.

I've also seen scripture memory cards that use The Message. Although I believe many parts of The Message are quotable and certainly memorable, I personally would caution someone against using The Message strictly as their only choice for memorization. A downside to any version of the Bible that overly depends on contemporary language remains in the reality that the language will not always be contemporary. To me, paraphrases tend to feel dated more quickly than other versions of the Bible.

That brings us back to the question regarding The Message's use in worship. Although I would use it in worship, I wouldn't do it regularly in place of other translations. Further, I believe it's important to let a congregation know when a paraphrase like The Message is being used rather than letting them wonder why "their Bible" doesn't sound like the reader's.

And for the person who still doesn't want to give up use of The Message as a primary Bible, I would recommend at least using one of Zondervan's parallel editions with the NIV, TNIV or NASB.

What are your thoughts? Feel free to share them in the comments.

Eugene Peterson's The Message (Top Ten Bible Versions, #5)

The Message is a paraphrase, not a translation of the Bible. What do I mean by paraphrase? Well, Peterson didn't try to do a word for word translation. Rather, he attempted to put the Scriptures in his own words with a flair for contemporary language. And, in my opinion, he did a very good job. The Message is most easily compared with with Kenneth Taylor's original Living Bible published in the early 1970's. That was a paraphrase, too, but this is so much better. When Taylor paraphrased the Bible, he didn't know the original languages. He took the 1901 American Standard Version and simply put it into his own words. What makes The Message different is that Peterson knows his biblical languages. He sat down with the Greek and Hebrew and created a paraphrase that is masterful in style and form. Truly comparable only to J. B. Phillips' own British paraphrase a few decades ago, Peterson's version is clever, stylistic and begs to be read aloud. I took a longer time reading through The Message than any previous version of the Bible I've read through. I think it's because I got caught up in the wording. I became more reflective, and found myself reading and rereading passages, comparing it to more traditional translations. I would call out to Kathy and say, "Listen to this" and read it to her.

I never recommend a paraphrase to be used as a sole Bible for study. I personally use a number of current Bible translations referenced against the Greek New Testament when I do serious study of the Bible. However, think of a paraphrase such as The Message as an aid, a Bible tool for insight into the meaning of the text. The obvious danger with a paraphrase is that as a person attempts to put the Bible into his or her own words, too much emphasis may be placed on personal interpretation. And, Like Taylor's and Phillips' previous works, paraphrases tend to be done by one person. In fact, I can't recollect any committee-based paraphrases of the Bible, but that's probably a positive in light of its use. The value of a true Bible translation lies in the checks and balances of a committee that works together on the final product. I've read some negative critiques of Peterson's work, including some questions about the way a particular verse reads or what seems to be unnecessary insertions into a verse, but I think overall these concerns are minor. I tend to judge any version of the Bible, whether paraphrase, form-driven or meaning-driven by what the translator(s) were attempting to do. The introduction to The Message states that "The idea is to make it readable--to put those ancient words that their users spoke and wrote into words that you speak and write every day." In regard to that, I believe that Peterson accomplished his purpose.

The Message has now been in complete form for a couple of years. However, it was initially released in portions. I picked up the New Testament in either 1993 or 1994. I remember taking it a number of times to an advanced masters level Greek class "Selected Passages from the New Testament" at Southern Seminary. I remember my professor (who will remain nameless) hated it. In particular, he hated Peterson's phrasings in Galatians. That's ironic because it was Peterson's paraphrases of Galatians from the Greek class he taught himself that first gained him notice and led to NavPress asking him to translate the whole Bible. But if my professor hated it, that's okay. Peterson wasn't writing for professors. He was writing for the regular guy on the street. The same way a missionary might translate the Bible to fit a foreign culture, Peterson seemed to be translating to reach the average American person at the turn of the 21st Century. The Message is one of the few translations that I've ever bought in portions. Usually, I wait until an entire Bible is completed before I pick one up, but Peterson's masterful paraphrase captivated me from the very beginning.

The Message is better experienced than explained. But here's a brief sample of selected passages from The Message itself:

I will admit that my favorite part of The Message is Peterson's rendering of the Bible's wisdom literature. He has a magnificent way of bringing Scripture's wisdom texts into modern contexts. Consider Prov 30:15-16...

A leech has twin daughters

named “Gimme” and “Gimme more.”

Three things are never satisfied,

no, there are four that never say, “That’s enough, thank you!”—

hell,

a barren womb,

a parched land,

a forest fire.”

In some of the earlier editions of the stand-alone OT portions, Peterson used Yahweh for God's divine name. I wish he had stayed with this, but opted to use GOD (in all caps) for the name of God in the final edition. I realize that use of the divine name can be offensive to those in Jewish contexts, but I would suggest that Yahweh could be used in the text and Lord could be read in its place in public readings. I would suggest this for any Bible version as certain passages only make sense if the emphasis is on God's actual name.

Curious as to where Peterson got his title? I figured this out simply by reading through it. The word Message (with a capital M) is used roughly 600 times in Peterson's paraphrase as signifying any divine communication from God. It is used in place of standard renderings such as "Thus spoke the Lord," "vision," "the word of God," etc.

The Message is certainly not perfect, and perhaps a paraphrase makes an easier target than most Bible versions for criticisms. I sometimes found myself wondering how this or that rendering could be justified with even the most extreme meaning-driven approach. But a paraphrase gives one extra freedom. I have also written in the past regarding The Message's deficient rendering of texts relating to homosexuality. I will include a link at the end of this entry.

Recently, as a tool for use with The Message, Peterson has released The Message Three-Way Concordance: Word/Phrase/Synonym.

How I use the Message. I've used The Message on and off for ten years now, usually either for devotional purposes or for public readings. I read selected passages from 2 Timothy when I gave my friend, Jason Snyder, his ordination charge. I've used it occasionally in my Bible study class on Sunday mornings to allow participants to hear familiar passages with "a different ear." I used it frequently with my students when I taught high school-level Bible courses at Whitefield Academy, especially when assigning longer passages of the Bible. When I read a passage from The Message (in a loud and clear voice with lots of drama and annunciation), they soon figured out it was too difficult to follow along in their translations. So they put them down and looked up to watch me. As I looked at their faces, these teenagers seemed to transform into little children listening to Bible stories. Most recently, I've used The Message for a Scripture reading in our worship service at church. The Message is also a good choice to use when speaking to a crowd that may be largely unfamiliar with the Bible, and it is certainly a good choice to give to someone who wants to read the Bible for the first time. I also noticed when we were in Louisiana last week that my mother-in-law is systematically reading through The Message.

What editions of the Message I Use. When the entire Bible was released in 2002, I gave away my portions to a friend and bought a hardback copy of the complete Bible. That's what I used for a couple of years (in addition to a software copy of the text that I have in Accordance).

More recently, I decided to get one of the newer editions that was not only in leather (I think it's leather), but also with verse numbering which was absent from all initial editions. That's how I came across The Message//Remix. It comes in both a hardback printed cover edition and a funky blue alligator bonded leather edition. I have the funky blue one.

How is The Message//Remix different from previous editions? Well, it fixed the one thing that frustrated folks who regularly use The Message--they added verse numbers! Yes, I understand why the original edition (which is still being published) does not have verse numbers. The biblical writers did not include chapter and number divisions in the original works. We have added these to make referencing particular passages easier. Peterson wanted people not to get bogged down the by unnatural interruption caused by verse references. He wanted us to read it as it was meant to be read in one continuous train of thought. Yet, it was often frustrating not to have the references included, especially when using The Message in conjunction with other translations. But the little known secret is that verse numbers have existed for a while in software editions where they are absolutely necessary. In this new edition, the publisher compromised and took a cue from the New English Bible and put the verse references out in the margins rather than interrupting the text with them.

Like the original edition, The Message//Remix keeps a one-column format which I prefer in a Bible. The paper used in this edition is a pleasing off-white. Book introductions have been revised from the original ones written by Peterson. They tend to be a bit shorter, but still just as powerful. I still like how Peterson introduces Ecclesiastes: "Unlike the animals, who seem quite content to simply be themselves, we humans are always looking for ways to be more than or other than what we find ourselves to be. We explore the countryside for excitement, search our souls for meaning, shop the world for pleasure. We try this. Then we try that. The usual fields of endeavor are money, sex, power, adventure, and knowledge."

The Introduction has new information as well, or at least a new layout--a remix--of the information about the paraphrase found in the original edition. But it's in a a more reader-friendly format. There is a section called "Listening to the Remix" that asks the question, "Why does a two thousand-year-old book still matter?" This part of the introduction seeks to distinguish the Bible from other literature such as Romeo and Juliet, Uncle Tom's Cabin, and Catcher in the Rye. There is a section that asks "Who is Eugene Peterson? Most Bibles don't have a person's name on them. So who is Eugene Peterson and why does he get his name on the front page of this particular Bible?" The best part of the introduction, in my opinion though lies in an essay called "Read. Think. Pray. Live" which truly describes how the Christian should incorporate God's Word into his or her life. I've seen the essay starting to show up a few other places outside this Bible lately, too. I don't know where it appeared first--here or somewhere else.

Finally--and some of you may find this silly--this Bible feels good in the hand. This is very subjective, and I don't know if you will even get what I'm saying. I'm just eyeballing here, but it measures about 7 1/2" X 5" and 1 1/2" thick. That's really one of my favorite sizes for a book. If you look at a library shelf of books from fifty years ago or more, lots of books were this size--hand size, I call it. It fits in your hand well. The cover is limp so it hangs (at the least the leather edition) like a Bible is supposed to.

For Further Reading:

- The Message Web Page (Navpress)

- History and FAQs (NavPress)

- The Message Wikipedia Entry

- Bible Researcher Page on The Message

- Better Bibles Blog Page on The Message (extensive discussion in the comments)

- Is the Message Soft on Homosexuality? (R. Mansfield)

- Follow-Up to the Message: What is the Proper Use of a Bible Translation? (R. Mansfield--added 7/13/2006)

Next entry: The Revised English Bible