Is a Paraphrase in the Eye of the Beholder?

06/13/2006 14:11 Filed in: Faith & Reason

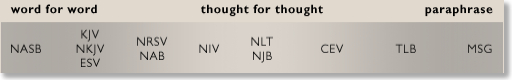

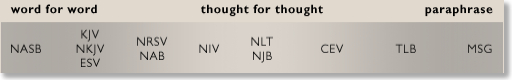

In the comments on my post regarding the New American Standard Bible, I was asked why I would refer to the New Living Translation as "a fairly extreme meaning-driven translation" when the chart I displayed earlier in entry shows the NLT to be right in the middle of the range of Bible versions. The chart repeated below is from the Tyndale House Publishers website, the owners of the NLT.

First of all, I didn't mean anything negative when I called the NLT an extreme meaning-driven translation. But perhaps I am guilty of poor communication. All I meant was that on the scale from very literal vs. very free, the NLT would be on the extreme side from the NASB. And for what it's worth, I was NOT factoring in paraphrases at all. In reflection, I may have made a poor choice in selecting a chart from a publisher's website. If you notice the chart above, what it does is place the NLT directly in the middle which gives the impression that the NLT is a "middle-of-the-road" translation. Personally, I don't think it is. To me, the NIV is a better candidate for the middle position. Of course, Tyndale refers to the NLT as a "thought-for-thought" translation, too, and they've put that in the heading of their chart which might also be a way for them to equate the NLT as the standard for all meaning-driven translations. I would not personally construct a chart quite like this, but then again, I'm not trying to market a Bible.

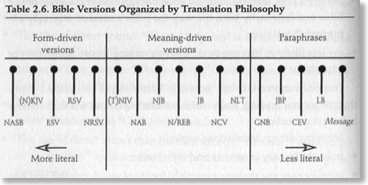

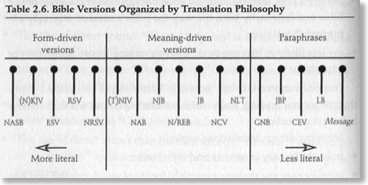

Anyway, in part of my response in the comments, I referred to a similar-in-concept, but different-in-result chart on p. 66 in David Dewey's book, A User's Guide to Bible Translations. Below is a scan of Dewey's chart regarding the span of Bible versions. If you have trouble viewing it, a larger version can be found at this link.

In looking at Dewey's chart, I came across something that intrigued me even more. Although I had seen this chart before, I never noticed that Dewey categorizes the Good News Bible and the Contemporary English Version as paraphrases. While I would consider the GNB and CEV very free dynamic equivalent or meaning-driven translations, I would have never thought of them as paraphrases, proper. In fact, although I haven't spent as much time with the CEV and can't speak for it as much as I could the GNB, I would have placed the New Living Translation to the right of both of these on the scale as being even freer. In my reading, the NLT comes closer to being a paraphrase at times than these other two, although I would still categorize all three as translations.

All of this begs the question as how one distinguishes between a translation and a paraphrase. It's almost like the famous quote from the Supreme Court justice who said in regard to pornography, "I may not be able to define it, but I know it when I see it!" To me, the GNB and CEV do not rank with what I think of as paraphrase (and neither does the NLT, which again, in my view is freer than these other two). However, the other three that Dewey includes in his chart--the J. B. Phillips NT, the Living Bible, and the Message--certainly do rank as paraphrases in my mind (although the JBP less than the other two).

So how does one designate a work as a paraphrase in distinction to "an extreme meaning-driven" paraphrase? On p. 42 of Dewey's book, he writes, "Strictly speaking, a paraphrase is not a translation from one language to another, but a rewording in the same language." Of course, Dewey admits that this definition doesn't cover Phillips' NT or Peterson's The Message since they were both rendered from the original languages. To allow for this, Dewey then further defines a paraphrase as "any free rendering, regardless of whether it was made from another English version or from the Greek and Hebrew." I suppose that such a broad definition would then allow one to include the CEV and GNB as a paraphrase, but then again, why not the NLT, too? The real question for Dewey would then have to be how he is defining "free" in the qualifying definition. Interestingly, in his section about paraphrases on pp. 42-43, Dewey does not include the CEV and GNB in his discussion, but he does mention the Living Bible, The Message, and J. B. Phillips' New Testament. On p. 203, Dewey says that a paraphrase such as the Message should never be used as a principle Bible, but if he considers the CEV and the GNB to be paraphrases as well, would he say the same thing about these versions? Many people do, in fact, use these two "translations" (my designation) as their primary Bible.

Perhaps, indeed, the Supreme Court justice's words do apply to this. What do you think? How does one distinguish between a translation and a paraphrase? Are freer translations like the GNB, CEV or NLT suitable as a primary Bible? Feel free to share your opinions in the comments.

Incidentally, although I'm nitpicking Dewey's definition of a paraphrase, I highly recommend this book as being one of the most current surveys available for all the options in Bibles out there today.

First of all, I didn't mean anything negative when I called the NLT an extreme meaning-driven translation. But perhaps I am guilty of poor communication. All I meant was that on the scale from very literal vs. very free, the NLT would be on the extreme side from the NASB. And for what it's worth, I was NOT factoring in paraphrases at all. In reflection, I may have made a poor choice in selecting a chart from a publisher's website. If you notice the chart above, what it does is place the NLT directly in the middle which gives the impression that the NLT is a "middle-of-the-road" translation. Personally, I don't think it is. To me, the NIV is a better candidate for the middle position. Of course, Tyndale refers to the NLT as a "thought-for-thought" translation, too, and they've put that in the heading of their chart which might also be a way for them to equate the NLT as the standard for all meaning-driven translations. I would not personally construct a chart quite like this, but then again, I'm not trying to market a Bible.

Anyway, in part of my response in the comments, I referred to a similar-in-concept, but different-in-result chart on p. 66 in David Dewey's book, A User's Guide to Bible Translations. Below is a scan of Dewey's chart regarding the span of Bible versions. If you have trouble viewing it, a larger version can be found at this link.

In looking at Dewey's chart, I came across something that intrigued me even more. Although I had seen this chart before, I never noticed that Dewey categorizes the Good News Bible and the Contemporary English Version as paraphrases. While I would consider the GNB and CEV very free dynamic equivalent or meaning-driven translations, I would have never thought of them as paraphrases, proper. In fact, although I haven't spent as much time with the CEV and can't speak for it as much as I could the GNB, I would have placed the New Living Translation to the right of both of these on the scale as being even freer. In my reading, the NLT comes closer to being a paraphrase at times than these other two, although I would still categorize all three as translations.

All of this begs the question as how one distinguishes between a translation and a paraphrase. It's almost like the famous quote from the Supreme Court justice who said in regard to pornography, "I may not be able to define it, but I know it when I see it!" To me, the GNB and CEV do not rank with what I think of as paraphrase (and neither does the NLT, which again, in my view is freer than these other two). However, the other three that Dewey includes in his chart--the J. B. Phillips NT, the Living Bible, and the Message--certainly do rank as paraphrases in my mind (although the JBP less than the other two).

So how does one designate a work as a paraphrase in distinction to "an extreme meaning-driven" paraphrase? On p. 42 of Dewey's book, he writes, "Strictly speaking, a paraphrase is not a translation from one language to another, but a rewording in the same language." Of course, Dewey admits that this definition doesn't cover Phillips' NT or Peterson's The Message since they were both rendered from the original languages. To allow for this, Dewey then further defines a paraphrase as "any free rendering, regardless of whether it was made from another English version or from the Greek and Hebrew." I suppose that such a broad definition would then allow one to include the CEV and GNB as a paraphrase, but then again, why not the NLT, too? The real question for Dewey would then have to be how he is defining "free" in the qualifying definition. Interestingly, in his section about paraphrases on pp. 42-43, Dewey does not include the CEV and GNB in his discussion, but he does mention the Living Bible, The Message, and J. B. Phillips' New Testament. On p. 203, Dewey says that a paraphrase such as the Message should never be used as a principle Bible, but if he considers the CEV and the GNB to be paraphrases as well, would he say the same thing about these versions? Many people do, in fact, use these two "translations" (my designation) as their primary Bible.

Perhaps, indeed, the Supreme Court justice's words do apply to this. What do you think? How does one distinguish between a translation and a paraphrase? Are freer translations like the GNB, CEV or NLT suitable as a primary Bible? Feel free to share your opinions in the comments.

Incidentally, although I'm nitpicking Dewey's definition of a paraphrase, I highly recommend this book as being one of the most current surveys available for all the options in Bibles out there today.