The Parallel Apocrypha

07/25/2006 10:14 Filed in: Books & Literature

Kohlenberger III, John R. (ed.). The Parallel Apocrypha. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

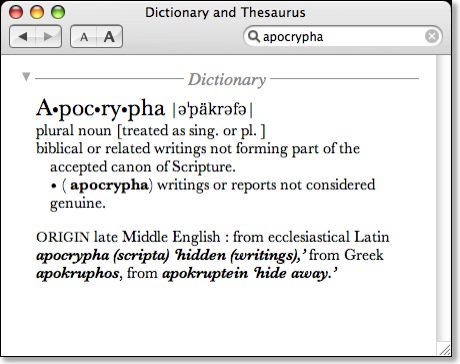

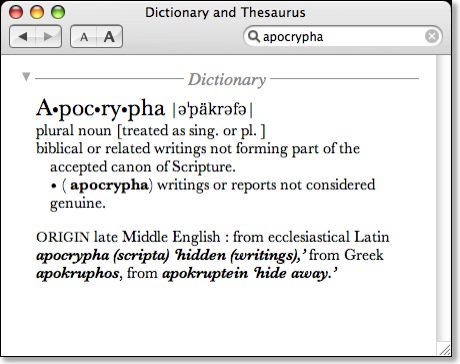

When Martin Luther translated the Bible into his native German, he included the disputed books--commonly known as the Apocrypha--in a section between the Old and New Testaments. In defense of doing so, he added this comment: "Apocrypha--that is, books which are not regarded as equal to the holy Scriputres, and yet are profitable and good to read." Add to that Augustine's sentiment (as quoted in the preface to the KJV) that "variety of Translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures," and you have The Parallel Apocrypha from Oxford Press.

Although published in 1997, I did not stumble across The Parallel Apocrypha until earlier this year. The book is edited by John Kohlenberger III, who at some point seems to have made parallel editions of just about every combination of the Scriptures imaginable. This work is considered parallel because over a two-page spread (for most texts), the Apocrypha is presented in Rahlfs' Septuagint Greek beside four Catholic translations (Douay, Knox, New American Bible and New Jerusalem Bible) and three Protestant translations (King James Version, Today's English Version, New Revised Standard Version).

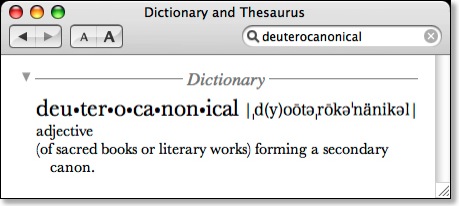

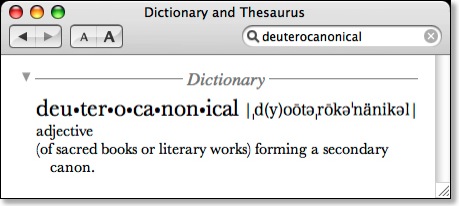

Until I obtained this volume, I didn't realize that all traditions do not hold identical lists of what is considered apocryphal (or deutercanonical in Catholic and Orthodox traditions). For instance, Roman Catholic, Greek and Slavonic Bibles all include Tobit, Judith, Greek additions to Esther, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, Letter of Jeremiah, Greek additions to Daniel (Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews/Bel and the Dragon), and 1 & 2 Maccabees. But 1 Esdras, Prayer of Manasseh, Psalm 151, and 3 Maccabees are only found in the Greek and Slavonic Bible, but are not in the Catholic Canon. 2 Esdras only appears in the Slavonic Bible and 4 Maccabees appears only as an appendix to the Greek Bible.

Interestingly, the only English translation included in The Parallel Apocrypha to cover all of these books is the NRSV, thus (I assume) making it the most ecumenical translation of the Bible in existence. The only book in the list not to be represented in the Greek is 2 Esdras because no complete Greek manuscript for it exists. Therefore, 2 Esdras is represented with Weber's edition of the Latin Vulgate (alongside only the KJV, TEV, and NRSV).

A very useful bonus to the texts themselves are a number of introductory essays. Judith Kovacs writes on "The Contents and Character of the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books" which provides an excellent introduction to the history, content and literary style of these books. Kohlenberger himself contributes an essay regarding the texts and translations found in The Parallel Apocrypha. If you've ever read any histories of the Bible in English, you may very well be interested in this short history of the Apocrypha in English. Finally, essays are included from a number of different faith traditions: Jewish (Sarah J. Tanzer), Orthodox (Demetrios J. Constanelos), Catholic (John J. Collins), Anglican/Episcopalian (Mary Chilton Callaway), Protestant (Walter J. Harrelson) and Evangelical (D. A. Carson). The addition of these essays helps to take the Apocrypha beyond its status as merely an historical religious document and places it squarely into a faith context.

The book itself is almost 1200 pages long, but the publishers used thin "Bible" paper, so The Parallel Apocrypha is only about one-inch thick. One translation that I wish Kohlenberger included is the Revised English Bible. I would have preferred the REB over the Knox Translation, however, I understand that the Knox Translation is significant because it is a more dynamic translation of the Latin Vulgate and sits well beside the more formal-equivalent Douay version, also from the Vulgate. And I suppose that there was a concerted effort on the part of the editor to include one more Catholic translation (four) over Protestant translations (three included) since these books take a more significant status in the Catholic tradition. Of course, if one considers that there are also renderings of the Apocrypha in the Revised Standard Version and the New Living Translation, it would seem that Protestants often pay more attention to these books than Catholics do themselves. Currently, there is no translation of the Bible in English from the Greek Orthodox tradition, but from what I understand, one is in the works.

In spite of all the Protestant translations in existence, I believe that generally, Protestants are the most guilty for neglecting the Apocrypha. Regarding the Apocrypha, I am in agreement with those who have gone before me in my own faith tradition that these books are not considered to be inspired Scripture. Even the writer of 2 Maccabees admitted as much when he wrote, "...So I will here end my story. If it is well told and to the point, that is what I myself desired; if it is poorly done and mediocre, that was the best I could do" (2 Mac 15:37-38, NRSV). Such sentiment hardly seems up to the level of being "God-breathed."

However, I would agree with Luther that these books are profitable and good to be read for two reasons. First, they are written by believers in the God of the Bible. Just as one might walk into a Christian bookstore and buy devotional literature or even historical fiction, the Apocrypha can be read in the same way (plus, I've always suggested the reading of Tobit to discover where Frank Peretti borrowed his best stuff). Further, and more importantly, the historical books of the Apocrypha, especially 1 & 2 Maccabees fill in the 400 year historical gap between the Old and New Testaments. If it's true that the New Testament cannot be understood apart from the Old Testament, it might be equally true that the culture and the historical situation of Jesus' day cannot be properly understood without the information derived from reading the Apocrypha.

When Martin Luther translated the Bible into his native German, he included the disputed books--commonly known as the Apocrypha--in a section between the Old and New Testaments. In defense of doing so, he added this comment: "Apocrypha--that is, books which are not regarded as equal to the holy Scriputres, and yet are profitable and good to read." Add to that Augustine's sentiment (as quoted in the preface to the KJV) that "variety of Translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures," and you have The Parallel Apocrypha from Oxford Press.

Although published in 1997, I did not stumble across The Parallel Apocrypha until earlier this year. The book is edited by John Kohlenberger III, who at some point seems to have made parallel editions of just about every combination of the Scriptures imaginable. This work is considered parallel because over a two-page spread (for most texts), the Apocrypha is presented in Rahlfs' Septuagint Greek beside four Catholic translations (Douay, Knox, New American Bible and New Jerusalem Bible) and three Protestant translations (King James Version, Today's English Version, New Revised Standard Version).

Until I obtained this volume, I didn't realize that all traditions do not hold identical lists of what is considered apocryphal (or deutercanonical in Catholic and Orthodox traditions). For instance, Roman Catholic, Greek and Slavonic Bibles all include Tobit, Judith, Greek additions to Esther, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, Letter of Jeremiah, Greek additions to Daniel (Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews/Bel and the Dragon), and 1 & 2 Maccabees. But 1 Esdras, Prayer of Manasseh, Psalm 151, and 3 Maccabees are only found in the Greek and Slavonic Bible, but are not in the Catholic Canon. 2 Esdras only appears in the Slavonic Bible and 4 Maccabees appears only as an appendix to the Greek Bible.

Interestingly, the only English translation included in The Parallel Apocrypha to cover all of these books is the NRSV, thus (I assume) making it the most ecumenical translation of the Bible in existence. The only book in the list not to be represented in the Greek is 2 Esdras because no complete Greek manuscript for it exists. Therefore, 2 Esdras is represented with Weber's edition of the Latin Vulgate (alongside only the KJV, TEV, and NRSV).

A very useful bonus to the texts themselves are a number of introductory essays. Judith Kovacs writes on "The Contents and Character of the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books" which provides an excellent introduction to the history, content and literary style of these books. Kohlenberger himself contributes an essay regarding the texts and translations found in The Parallel Apocrypha. If you've ever read any histories of the Bible in English, you may very well be interested in this short history of the Apocrypha in English. Finally, essays are included from a number of different faith traditions: Jewish (Sarah J. Tanzer), Orthodox (Demetrios J. Constanelos), Catholic (John J. Collins), Anglican/Episcopalian (Mary Chilton Callaway), Protestant (Walter J. Harrelson) and Evangelical (D. A. Carson). The addition of these essays helps to take the Apocrypha beyond its status as merely an historical religious document and places it squarely into a faith context.

The book itself is almost 1200 pages long, but the publishers used thin "Bible" paper, so The Parallel Apocrypha is only about one-inch thick. One translation that I wish Kohlenberger included is the Revised English Bible. I would have preferred the REB over the Knox Translation, however, I understand that the Knox Translation is significant because it is a more dynamic translation of the Latin Vulgate and sits well beside the more formal-equivalent Douay version, also from the Vulgate. And I suppose that there was a concerted effort on the part of the editor to include one more Catholic translation (four) over Protestant translations (three included) since these books take a more significant status in the Catholic tradition. Of course, if one considers that there are also renderings of the Apocrypha in the Revised Standard Version and the New Living Translation, it would seem that Protestants often pay more attention to these books than Catholics do themselves. Currently, there is no translation of the Bible in English from the Greek Orthodox tradition, but from what I understand, one is in the works.

In spite of all the Protestant translations in existence, I believe that generally, Protestants are the most guilty for neglecting the Apocrypha. Regarding the Apocrypha, I am in agreement with those who have gone before me in my own faith tradition that these books are not considered to be inspired Scripture. Even the writer of 2 Maccabees admitted as much when he wrote, "...So I will here end my story. If it is well told and to the point, that is what I myself desired; if it is poorly done and mediocre, that was the best I could do" (2 Mac 15:37-38, NRSV). Such sentiment hardly seems up to the level of being "God-breathed."

However, I would agree with Luther that these books are profitable and good to be read for two reasons. First, they are written by believers in the God of the Bible. Just as one might walk into a Christian bookstore and buy devotional literature or even historical fiction, the Apocrypha can be read in the same way (plus, I've always suggested the reading of Tobit to discover where Frank Peretti borrowed his best stuff). Further, and more importantly, the historical books of the Apocrypha, especially 1 & 2 Maccabees fill in the 400 year historical gap between the Old and New Testaments. If it's true that the New Testament cannot be understood apart from the Old Testament, it might be equally true that the culture and the historical situation of Jesus' day cannot be properly understood without the information derived from reading the Apocrypha.