NLT Study Bible: Hands-On Review [UPDATED]

07/30/2008 00:42 Filed in: Faith & Reason

“But my child, let me give you some further advice: Be careful, for the publishing of new study Bibles is endless, and carrying more than one in your book bag wears you out”

(modified from Ecclesiastes 12:12, NLT).

I received the Genesis sampler of the NLT Study Bible (NLTSB from this point forward) a few weeks ago. I literally read every word of it (the same as I had done to the Life Application Bible Gospel of

Mark in the Living Bible way back in the late eighties!) to get a feel for the direction this new study Bible takes. Since last Friday, upon receiving an advance copy of the entire Bible in the mail, I have spent a good bit of time reviewing the full product as well. At this point I can readily suggest that the NLTSB really does bring something new to the already crowded study Bible table.

The NLTSB contains lots of great features that I’m not going to spend a whole lot of time discussing since a number of other reviews are starting to show up on the web that do a fine job covering these. You can “Tour the Features” on the NLTSB website. Also, you can see a list of the contributors at the website as well--a veritable “who’s who” of Evangelical scholarship, but one that represents mainstream thought and offers a variety of perspective within certain boundaries.

IN KEEPING WITH WHAT HAS GONE BEFORE. I have no doubt that study Bibles are big business. And it seems to me that a translation has reached a certain level of acceptance when it begins to show up on shelves in study Bible forms. Study Bibles come with different approaches. There are study Bibles written from the viewpoint of an individual (Scofield, Ryrie, Dakes, MacArthur). Recently there has been a trend for study Bibles to come wrapped around a particular subject (apologetics, archaeology, literary features) or even specific theological perspectives. These two categories are fine if a reader really like the viewpoint of a particular individual or if the reader has interests in a particular subject and wants to discover how that subject relates to Scripture. But for me, I’ve always felt a bit more comfort in study Bibles that offer information of a more general nature and ones that have the perspective of not one particular writer or theological viewpoint, but from from the work of many individuals. In the last two decades, the NIV Study Bible has reigned supreme in this realm as a kind of standard that most study Bibles most often get compared to. The NIV Study Bible has even been adapted to three other translations: the KJV, NASB, and TNIV. Other committee-produced study Bibles in this kind of category include the New Oxford Annotated Study Bible, the Life Application Study Bible (also adapted to numerous translations) and the Jewish Study Bible, to name a few.

2008 sees two new study Bibles in the multiple-contributor category, and that is the NLT Study Bible, the subject of this review as well as the forthcoming ESV Study Bible. And in addition to the kind of standard (at least for Evangelical circles) set by a work like the NIV Study Bible, I would suggest that although it may not be at first apparent, there is another study Bible that is influential upon the NLT Study Bible. I’m referring to the NET Bible with its 60K+ notes. Although as of yet, not widely accepted, he NET Bible raised the bar in a number of ways for study Bibles, and in my opinion its influence is seen in at least three areas in the NLTSB.

The first is the NLTSB’s greater interaction with the original languages. It’s not uncommon to see transliteration of Greek and Hebrew words in the NLTSB’s study notes, even transliterated words beyond those defined in the NLTSB’s brief word study dictionary (more about that to come). Any reader familiar with the NET Bible knows that original language words are regularly incorporated into the notes both in their Greek and Hebrew form as well as a transliteration. The NLTSB offers only transliteration, but this probably suffices for the majority of its target market.

Second, like the NET Bible [print version], the NLTSB intermixes textual notes of the translation with its other notes. This is actually my largest criticism for the NLTSB. The NET Bible can get away with intermixing its textual notes because ALL of the notes came from the translation committee. Reading the NET Bible’s notes is like sitting in on an extended translator’s meeting. As with any translation, I’m very much interested in the footnotes added to the NLT text by the translators as a completely different level of authority and importance from the commentary of the study Bible itself. So the fact that the new 2007 edition of the NLT has a footnote in Gen 10:15 for “Hittites,” reading “Hebrew ancestor of Heth” is totally lost on me because I can’t distinguish it from the rest of the study notes. Even though the study notes in the NLTSB offer an explanation of the footnote, I have no indication that the original footnote itself is from the translation committee. There’s not even an indicator within the text itself that the word “Hittites” required clarification by the translators. If there was one major feature I’d recommend changing in the NLTSB in subsequent printings, it would be to separate the translator’s notes from the commentary.

Another influence of the standard set by the NET Bible: while the number of notes are at a greater number than some study BIbles (the NLTSB boasts 25,900 vs. the NIV Study BIble’s 25,000), these notes in the NLTSB are shorter and more to the point.

But what kind of notes are these? A few weeks back, I asked Tyndale if the study notes in the NLTSB were merely a condensation of Tyndale’s Cornerstone Biblical Commentary series which is also based on the NLT. I was told that it is not, and in fact the study notes in the NLTSB are entirely new, written specifically for the NLTSB (plus, the Cornerstone series is not complete yet).

SO WHAT’S DIFFERENT HERE? One of the promotional charts for the NLTSB compares the approach of it to other popular study Bibles. This is marketing copy, of course, so its value to you will vary, but the various study Bible approaches described this way:

“Using the NLT Study Bible is like being led through Scripture by a caring Bible teacher.”

“Using the NIV Study Bible is like being led through Scripture by a historian.”

“Using the Archaeological Study Bible is like being led through Scripture by an archaeologist.”

“Using the MacArthur Study Bible is like being led through Scripture by a theologian.”

Now, some may argue with any of those explanations on a variety of fronts, but the one major-selling study Bible I saw missing from this list was Tyndale’s own Life Application Study Bible. So I asked Tyndale how the two Bibles differed. I was told that “The Life Application Bible is like being led through Scripture in a discipleship program or by an application-oriented exegete.”

Okay, so the NLTSB is different because, to quote Sean Harrison from the NLTSB Blog,

“Basically, the NLT Study Bible focuses on the meaning and message of the text as understood in and through the original historical context. I don’t see other study Bibles focusing so fully on that. Some study Bibles focus on helping people to accept a particular doctrinal system, while others focus on “personal application.” Others simply provide interesting details about the context, language, grammar, etc., without asking how that information will impact people’s understanding of the text. Still others focus on a particular type of study methodology—topical study, word study, etc. Our goal, by contrast, was to provide everything we could that would help the readers understand the Scripture text more fully as the original human authors and readers themselves would have understood it.“

Of course these kind of descriptions can often overlap. I can see the difference from the Life Application Study Bible, but is the NLTSB all that different in approach from the NIV Study Bible (and its cousins)? Well, you will have to decide for yourself, but I do think it does a few things better, and I will describe those below.

And on a related note, in spite of distinguishing the NLTSB from the Life Application Bible, some notes such as the one discovered by blogger David Ker would make one wonder if there’s not an overly homiletical interest in some of the notes. So, maybe there actually is here and there, but they aren’t necessarily the norm. In fact, as I pointed out in the comments to David’s blog, if you turn to the notes at the other end of the Bible in a book like Revelation, I don’t see any of these kind of preachy statements such as in the last sentence of David’s example. In fact, to quote myself, “[the notes in Revelation] tend to stay with the text, illuminating yes, but not falling into homiletical application. The notes on Revelation also refreshingly tend to avoid any overt connections with interpretational schemes.” The Revelation notes, by the way, were written by Gerald Borchert.

Since the study notes for different biblical books were written by different writers, there may be some consistency issues, but David’s example does not seem to be the norm.

Really, there’s not going to be an unexpected twist to my review. I believe the NLTSB is a solid product. Having said that, however, there are a number of areas in which I believe the NLTSB does things exceptionally well. These are described below.

INTRODUCTIONS WITH SUBSTANCE. Anyone familiar with study Bibles expects to read a one to two page introduction before each biblical book. Included in that introduction are the obligatory sections of author, time of writing, type of literature and an outline. This is where the NLTSB goes above and beyond. Before one ever comes to the introduction to Genesis, the reader will find a four-page, three-column introduction to the Old Testament as a whole. Following that is a four-page essay and table on archaeological sources for Old Testament background. Then the reader finds a separate three-page, three-column introduction to the Pentateuch. Only then will the reader find the expected introduction to the book of Genesis. Thus the NLTSB begins to approach the state of not only functioning as a study Bible but an introduction to the Bible as well.

Of course since study Bibles are usually aimed at a more mainstream audience, I’m always interested to see how such resources handle discussions such as authorship. It doesn’t surprise me for an Evangelical resource such as the NLTSB to reject Wellhausen’s Documentary Hypothesis (my own study and convictions reject it as well). However, I remember being gravely disappointed that in the original 1985 NIV Study Bible that this major theory of Pentateuchal origins could be so easily dismissed in one short sentence. Taking a much different approach, I was pleased to see that in the NLTSB, the issue is not so easily swept under the rug. Although the Documentary Hypothesis is rejected, it is rejected with seven paragraphs of explanation as to why.

On the other hand, Evangelicals always seem more comfortable (for the most part) with source criticism in the New Testament. So, for instance, in the introduction to the Gospels (which is one of four articles before ever reaching the introduction to Matthew), Markan priority for the Synoptics is accepted as probable and credence is also given to the Q source:

“There are also 250 verses of Jesus’ sayings that are shared by Matthew and Luke but not found in Mark, so most scholars believe that they both used a common source, perhaps oral, referred to as Q (from German Quelle, meaning ‘source’ ).”

Some may be interested to know that there is also a separate introduction to Paul’s pastoral epistles in addition to a general introduction to his work.

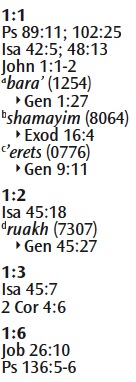

The NLTSB reinvents the cross reference column making it much more useful than merely offering other verses to look up. There are these basic kinds of cross references included, but just enough--not too many. Parallel passages are indicated by two double forward slash marks (//). Asterisks mark intertestamental quotations.

Another new feature in the cross references relate to word studies tied to the original languages. Certain major Hebrew or Greek words are transliterated within the reference column along with its Tyndale-Strong’s number. A reader can look these words up in the “Dictionary and Index for Hebrew and Greek Key Word Studies” in the back of the NLTSB. This dictionary serves as a brief lexicon for about 200 major biblical words. Underneath the reference, a triangled bullet indicates the next occurrence of the particular word much like a chain reference Bible.

Thus the NLTSB manages to combine in its reference system the best qualities of a reference Bible as well as the features of other works such as The Hebrew-Greek Key Study Bible and The Thompson Chain Reference Bible.

RANGE OF SOURCES. Often study Bibles tend to come across as closed systems of reference rather than leading the reader to further information. Many study Bibles simply don’t refer the reader to other works at all. Perhaps this is another influence of the NET Bible which offers references to books and articles right within its notes. While the NLTSB doesn’t do this in the study notes, there is a “Further Reading” section in each introductory article. I was both surprised and delighted to see such a wide range of selections.

These recommendations aren’t relegated to simply Christian writers. Robert Alter, a well known scholar in the Jewish Studies department at Berkeley is recommended further reading for 1 & 2 Samuel. And even among Christian writers, there is a great deal of diversity. Take for instance the introduction to the Book of Psalms. Familiar readers will know there is a VAST difference between the work of James Montgomery Boice on the Psalms and that of Marvin Tate from the Word Biblical Commentary (the latter of whom wrote one of my two recommendation letters to the doctorate program). And in the introductory article on the Book of Daniel, a very traditional scholar like E. J. Young is listed right along with John Goldingay who dates the Book of Daniel much later than the events described therein.

Now, I have to admit that I believe that such diversity among recommended sources is too often sadly rare in some Christian circles. But this demonstrates a confidence in the editors of the NLTSB that readers can make their own informed decisions in regard to the biblical writings. Frankly, such openness is both surprising and refreshing.

Unfortunately, full bibliographic information is not included with the list of further reading recommends, but simply the name of the author and the title of the work--with the exception of volumes from the Cornerstone Biblical Commentary. All completed volumes of the CBC are included in the appropriate lists as would be expected from a Tyndale publication, and the CBC is the only series that enjoys the mention of its name in the “Further Reading” lists. As for the other recommendations, an author’s name and title of the work is probably all one needs to track down any of these volumes at most online resellers.

ACKNOWLEDGING OTHER TEXTS. The writings of the Bible were not written in a vacuum, of course. But from many study Bibles on the market the reader wouldn’t necessarily know otherwise. Sometimes a study Bible will have an included article on the books of the Apocrypha and reasons why Protestants don’t read them, but very little more attention is paid to these books. Most study Bibles include a begrudging reference to 1 Enoch in Jude, but offer little more.

So I was quite amazed Sunday when looking at the article on “Circumcision” that accompanies Acts 15 to read this statement: “For Jews, it had religious significance as the sign of the covenant that God had established with the people of Israel (7:8; Gen 17:9-14; Josh 5:2; John 7:22; Sirach 44:20).” Yes, right along with references to other biblical books was a reference to the Apocrypha. So I looked further, and I found that references to other Jewish literature abounds in the study notes! The note for Romans 4:1 refer the reader to the Prayer of Manasseh, Jubilees, 1 Maccabees and Sirach by way of background. The note for Matt 5:31 quotes the Mishna! I can’t recall seeing so much interaction with extrabiblical Jewish literature in any other study Bible from an Evangelical publisher ever before.

Two more features of note: (1) a five-page, three-column article with timeline titled “Introduction to the Time After the Apostles” follows Revelation describing the process of canonization; (2) the “NLT Study Bible Reading Plan” incorporates all the additional articles and introductions and if followed five days of the week can be completed in five years.

WHAT’S NEXT? The NLTSB won’t be widely available until it hits the retailers mid-September. However, Tyndale has quite a few events coming up in conjunction with the release of the NLTSB. In August, the complete text and all the features of the NLTSB will be released on the internet. This will include fully searchable text with hyperlinked cross references. Unlimited access comes with the purchase of any NLTSB, and others can obtain a 30-day free trial.

Also in August, NLTSB General Editor Sean Harrison will host live “webinars” demonstrating features of the Bible and answering questions.

Simultaneous with the release of the NLTSB on September 15, software editions of the study Bible will be made available for three platforms (Libronix, PocketBible, and WORDSearch (What? Where’s the Accordance module?!).

The NLT Study Bible website is great place to keep up with these developments and to explore the features of the NLTSB. There’s an engaging blog at the website and an errata page has already been started. I commend Tyndale for the errata page as there’s bound to be errors in a project of this scale, and they’re honest enough to make them known (if only this had been done for Zondervan’s Archaeological Study Bible which was rife with errors).

And if you weren’t able to get your hands on one of the early copies of the NLTSB, be sure to place yours on pre-order.

Overall, I’m impressed with the features of the NLT Study Bible, and I truly believe it is yet another step in facilitating the New Living Translation as a choice for serious Bible study.

ONE MORE THING. I failed to mention that the NLTSB breaks with the recent trend for small type in study Bibles by offering a surprisingly larger and readable typeface. The type in the NLTSB is larger than the typeface in the Archaeological Study Bible, the TNIV Reference Bible and even the TNIV Reference Bible. Tyndale was able to do this by opting for a more traditional two-column biblical text instead of a single-column as with most recent study Bibles. Single-column text requires more pages because it does not use space on the page as efficiently as double column text--especially in poetic passages.

Although I’m a fan of single-column text, the larger typeface in the NLTSB is a welcome “feature.” The study notes conserve space even further by using a triple-column layout and thus are easier on the eyes as well.